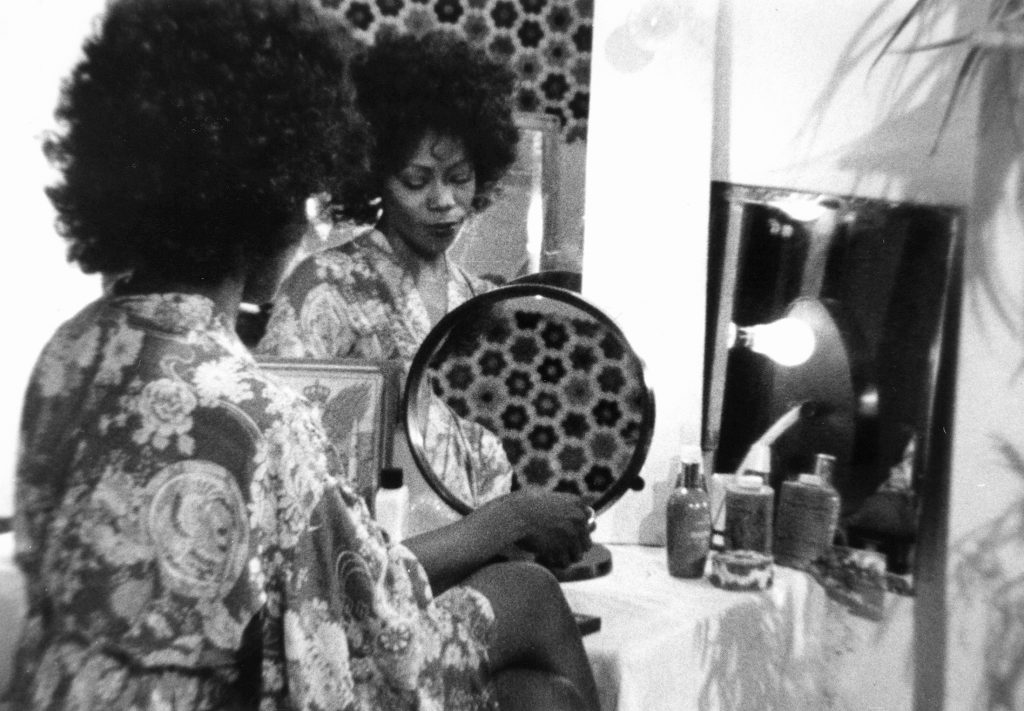

Riddles of the Sphinx. Directed by Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, 1977.

Grace Barber-Plentie is a freelance film writer, and one third of Reel Good Film Club, a film club dedicated to diversity in film. She is the Marketing Assistant for BFI Distribution and DVD. @gracesimone

The lure of Laura Mulvey first drew me in like it does most: by discovering her seminal text “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” [PDF here] (although in all honesty, the name may have been on my radar thanks to a brilliant and underrated joke made in Parks and Recreation). However it wasn’t until I was studying film at university that I was made aware of the full power of Mulvey’s words – and most importantly that not only is she an iconic essayist, but also a filmmaker, having directed films alongside her husband, fellow film theorist Peter Wollen. It’s through lack of resources on my own part, lack of screenings from the British film industry in general and lack of emphasis on Mulvey’s role as a feminist filmmaker that I’m only just now watching Riddles of the Sphinx. I’m grateful that Club Des Femmes are giving audiences across the UK a chance to witness not just the words but the vision of one of the UK’s most prominent feminist thinkers.

Riddles is made up of five parts, beginning with Mulvey recalling the Greek myth of Oedipus and the Sphinx, before moving into the life of protagonist Louise as she attempts to reconcile her new motherhood with her identity, and ending with two dreamlike sequences.

As I sit down to watch the film, particularly its opening, I’m reminded of the fact that I’m not the biggest fan of experimental cinema. While I love watching new ways of storytelling and shaping narratives, I feel that being honest about not quite “getting” the film form is better than pretending to like it. However I feel a sense of calm in the film’s opening scene. Anything associated with – and re-examining – Greek mythology deeply resonates with me.

It’s also rare to see a woman telling a story directly to camera, yet here, in the opening scene, Mulvey herself faces us, breaking the fourth wall to tell her tale amidst imagery of Greek mythology and ancient Egypt. Is this the female gaze that we hoped for: Mulvey positioning the female subject (in this case, herself) looking directly into the camera, and the female audience members staring back to meet her gaze?

There’s a reason why Mulvey’s feminism is enduring until this day, and that’s because she spots trends and behaviours long before we as a society admit to them. In Riddles, she shows us an unbiased depiction of the joys and tribulations of motherhood – wanting to escape but also wanting to cling fiercely on to your child.

Riddles of the Sphinx is meandering, swirling. The film pulses with Mike Ratledge’s experimental score, helping us enter Louise’s psyche. When Louise leaves her child to go to work, the camera pans across rooms slowly, taking in sections of various conversations. We hear women discuss work, home and family. Discussions about milk are valued just as much as any dramatic revelations.

It’s disheartening to think that in 2018, Riddles can still feel fresh and unique and new. But there is something radical in the way Mulvey lays what we would think of as “issues” on the table and treats them with frankness and honesty, coupled with her experimental visual style and hypnotic score. But maybe this is the problem of being the first, or at least a pioneer of something: future works will always be held up to your standard.

Riddles is action in motion. Not only does Mulvey seek to challenge film through her written texts, she then tries to abolish and upend them in her film works. Rather than preach one thing and then practise another, as can be the downfall of filmmakers, she ties together her feminist film theory and her feminist filmmaking with a bow, challenging us the audience to receive it, and challenging other filmmakers to follow suit.

With renewed interest in the film in 2018, the Sphinx is re-emerging. It was never defeated, never fully gone, just lying dormant. It is resurrected.