DAISIES + SAUTE MA VILLE! screened at the Lexi as part of their Summer Film School, and CdF’s So Mayer went along to offer an introduction to Vera Chytilova’s wild stylings.

There’s no film that’s quite like it, so we decided to take a look through the lens of feminist art…

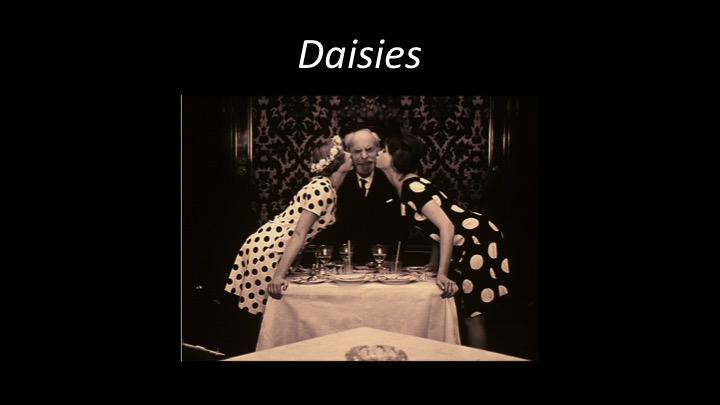

Lots of you will have seen Hannah Gadsby’s criticism of male-oriented “genius” art history in Nanette – I want to offer the complementary perspective. Like Judy Chicago’s legendary grand-scale vagina-plate installation The Dinner Party, I am going to argue that DAISIES offers a brilliant catalogue of the way feminist artists have claimed a “seat at the table”. Quite literally, in the case of the film’s final scene –

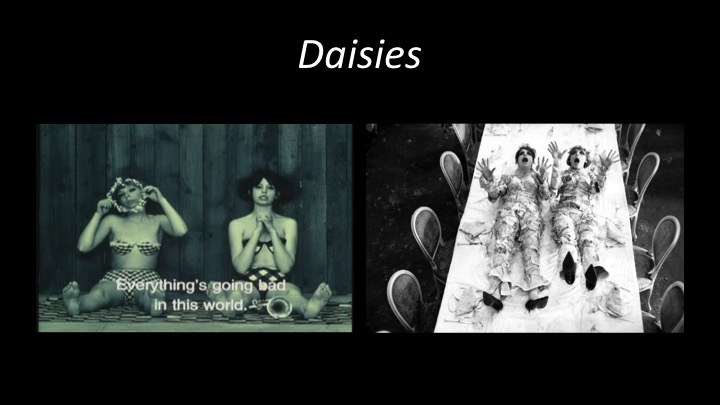

A banquet for state officials: disrupted by the playful, desiring eating habits of Marie 1 and Marie 2. This is the culminating performance of all of the anarchic gestures we’ve seen – and it’s the scene that led Soviet authorities to ban the film for “food wastage.” A fascinating charge given how strongly food is associated with disruptive embodied female pleasure not only in the film, but in feminist art of the time.

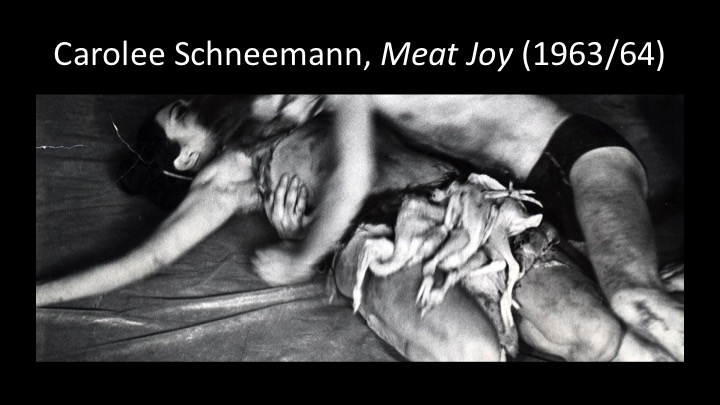

One of the most disruptive and controversial early feminist artworks, Meat Joysaw Schneeman and seven other naked-ish figures crawl and roll about, playing with sausages, raw fish, raw poultry, wet paint, transparent plastic, ropes, scraps of paper, and one another. Schneemann described her work as an ‘erotic rite’ and a ‘celebration of flesh as material.’

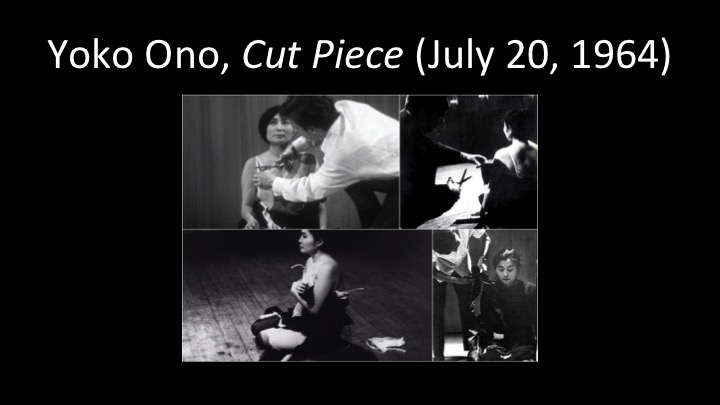

New York in the early 1960s was a febrile time of “happenings,” represented in art history as a male-dominated genre. But from the start, Schneeman and Yoko Ono were using their own bodies to challenge the assumption that women were just “pieces of meat” in the art world. In CUT PIECE, Ono sat alone on stage, and audience members could come on stage and cut away a small piece of her clothing. She changed the dynamic in modern art between the artist and audience, making her body central, and making the audience complicit.

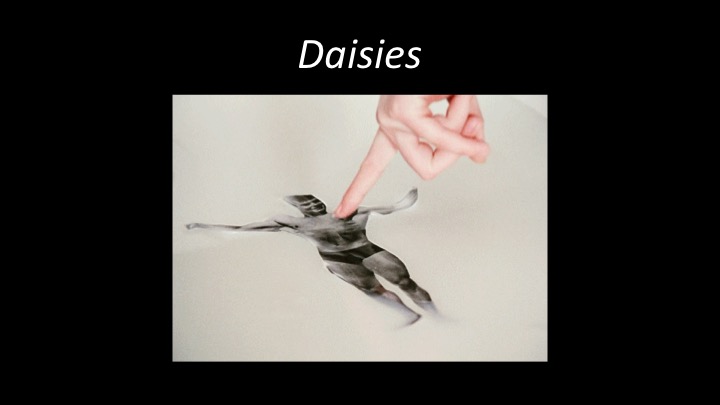

DAISIES equally asks us to play along with its non-linear narrative and its jokes about film form, while realising what’s at stake for women given that the history of visual art so frequently objectifies women – particularly the scene where the girls cut each other to pieces!

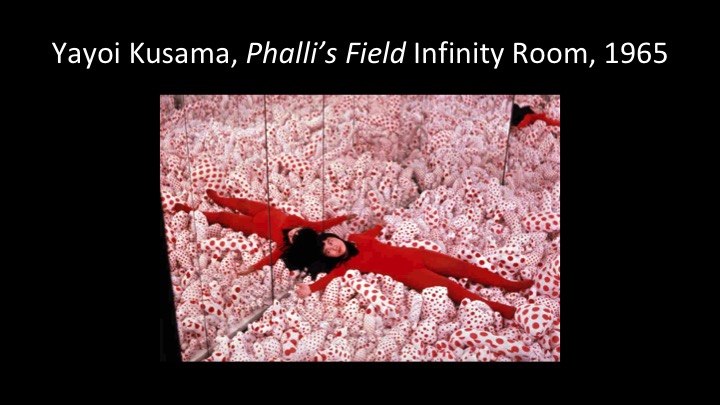

As in CUT PIECE, there is a strong interest in what clothing says about women’s bodies in DAISIES, with striking, motivated costume choices that often contrast the Maries with their formal public environments or blend them into domestic or pastoral space. The film is particularly known for its polka-dots…

Which echo those of another Japanese artist who arrived in New York in the 1960s and created feminist happenings. Yayoi Kusama’s use of her signature polka dots goes back to this very early infinity room, in which the mirrored dots take on a cosmic implication, but also draw attention to the artist’s body placed disruptively among the phalli!

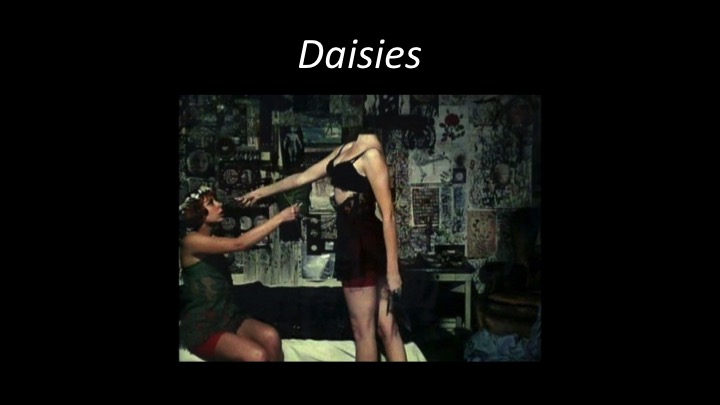

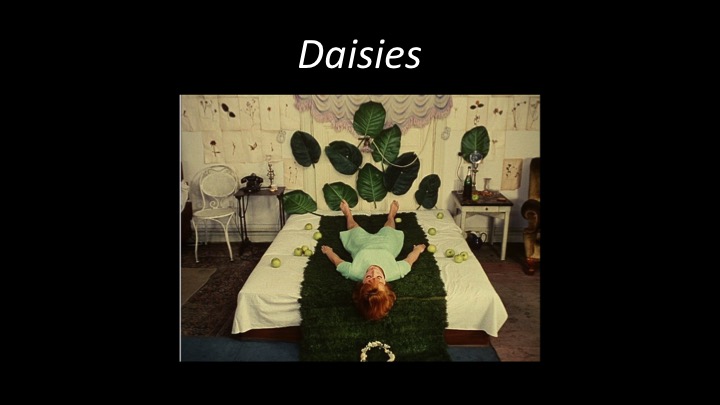

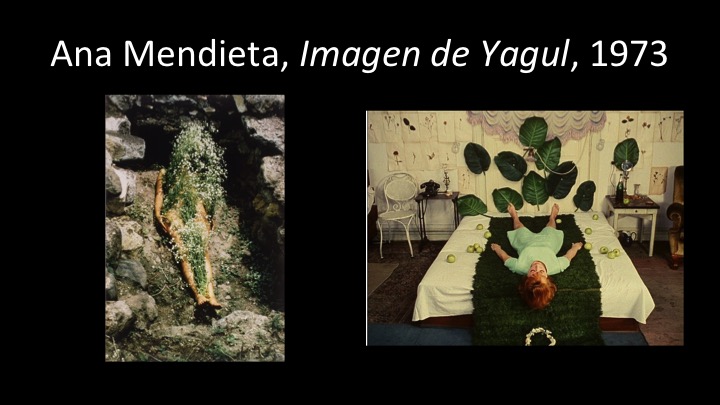

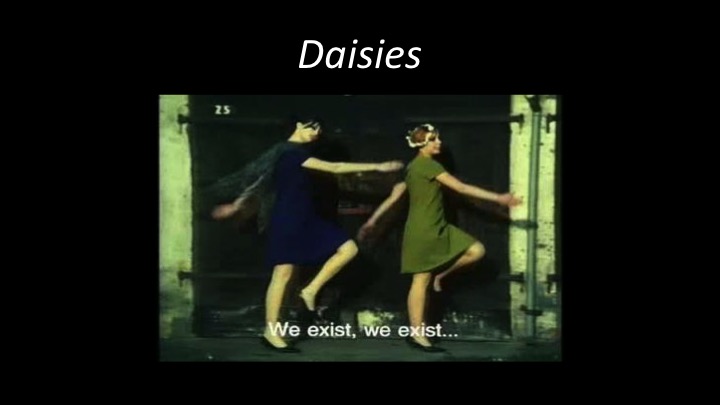

DAISIES constantly disrupts our expectations of what women’s bodies do in space, whether domestic, public, or pastoral – in some scenes, such as this, by crashing them together. Watch the apples and trees that move through the film, which bring together references to Cezanne’s still lives and to Genesis… and also note that Chytilova’s subsequent film was called THE FRUIT OF PARADISE.

The vexed relationship of Woman and Nature was the subject of some of the great feminist art of the first half of the twentieth century – not least in the work of two artists who met in Mexico during WWII. Kahlo’s paintings often merge self-portraits of the artist with the fecund, growing world in a way that is both sensual and painful. Carrington’s equally disturbing dreamscapes, with their imagined beasts, take the Dejeuner sur l’herbe to a nightmarish place where bodies are distorted, transparent and floating.

In the 1960s and 70s, feminist artists such as Chytilova were inspired by the work of their precursors – but were also looking for a way to rehabilitate the relationship between the body and the natural world. Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta’s most famous work, her Silhuetas, placed her body directly in the landscape, often disappearing into it under plant matter or mud, or leaving only her outline burned or marked on the earth. I don’t know whether Mendieta saw DAISIES while studying painting in Iowa in the late 1960s, but certainly both Chytilova and Mendieta were responding both to a feminist history of art that was just about being recognised, and to a nascent ecofeminist zeitgeist.

It’s no co-incidence that these connections and flows of inspiration appear around this time: Linda Nochlin’s famous essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ appeared in 1971. But Nochlin’s article – and indeed mainstream feminism – was very focused on the West. As Soviet filmmaker Kira Muratova’s 1960s films make apparent, gender equality was nominally part of the Soviet communist platform.

BRIEF ENCOUNTER, from 1967, looks at the contrasting lives of two women in love with the same man: his wife, a high-ranking state functionary, and his younger lover, who becomes her maid. The film’s non-linearity and its satirical critique of the state through the officious Valentina who does not believe in love, sent the film to the censor’s vault. In Larisa Shepitko’s film WINGS, released the same year as DAISIES, we see the fate of women who served in the Soviet armed forces in WWII and then were returned to the home without honour after the war.

Chytilova remained resistant throughout her life to the word ‘feminism’ as a Western import, preferring to espouse ‘individualism’ as her credo – an argument for the self above and beyond the state, which is palpable in Muratova’s and Shepitko’s work as well. But whereas they locate that individualism in family and romantic love, for Chytilova it is more anarchic and even less social. She also took a less social realist approach to satirising the confines of Soviet-sphere gender politics, with her critiques offered in the form of cabaret skits that could come straight from the pre-war world of the Weimar Republic and Dada, as well as Prague’s own history of absurdist theatre and art. In particular, the film’s use of collage offers a throughline of feminist art history, from…

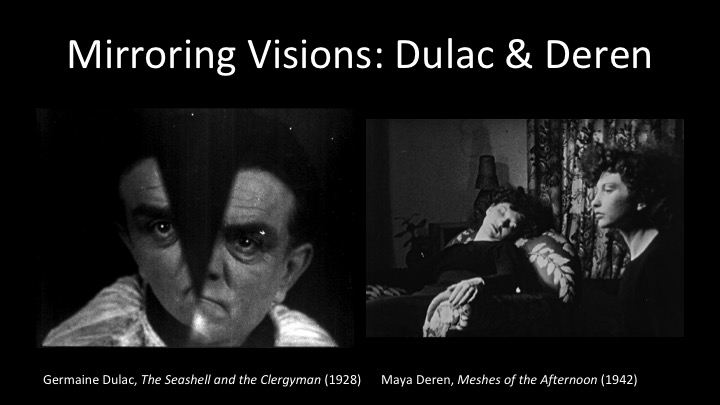

Germaine Dulac’s and Maya Deren’s early experiments in cinema, using mirrors and optical printing to create multiples, doubles and dream-like narratives…

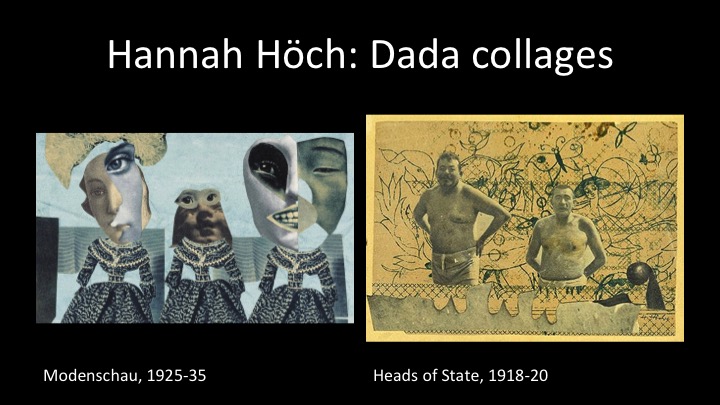

Hannah Hoch’s Weimar-era political collages, often only the size of a postcard…

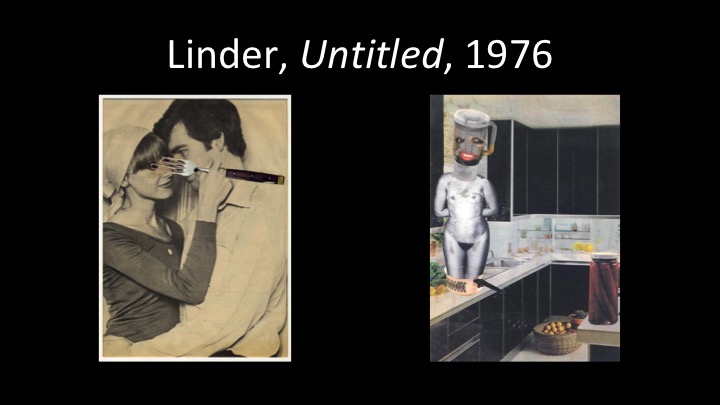

To the postcard-style feminist photomontage of British punk/post-punk artist Linder…

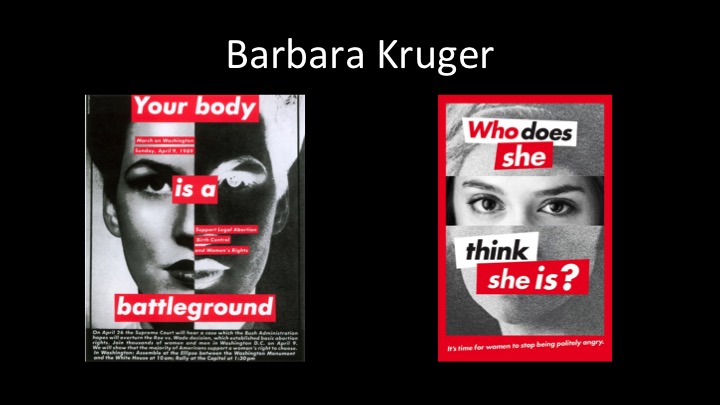

and the famous political poster and postcard magazine cut-ups of American conceptual artist Barbara Kruger which, like DAISIES, intervenes into the representations of women in advertising and media – and into the very idea of women’s bodies as public property.

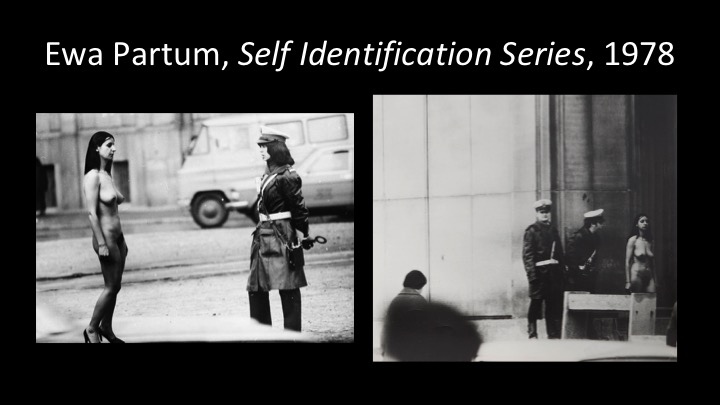

By putting the bodies of the Maries front and centre, and desexualising nudity through the Maries’ confrontational insistence on speaking their minds and being aware of the gaze, Chytilova also prefigures the next wave of feminist art in the Soviet sphere –

Photographer and performance artist Ewa Partum combined the two modes – collage and performative confrontation – in her series SELF IDENTIFICATION, photo-montages in which cut-out images of her naked body are pasted into her street photography of Warsaw life – and particularly creating confrontations with state power, showing the limits of the self and individualism under the state.

Performance artist VALIE EXPORT, who named herself after a popular cigarette brand, took a more in-your-face – or in-your-hands – approach to placing the female body in public, and to questioning the male viewer’s investment in looking with her work Tap and Touch Cinema, where she challenged the viewer to engage without the medium of the screen.

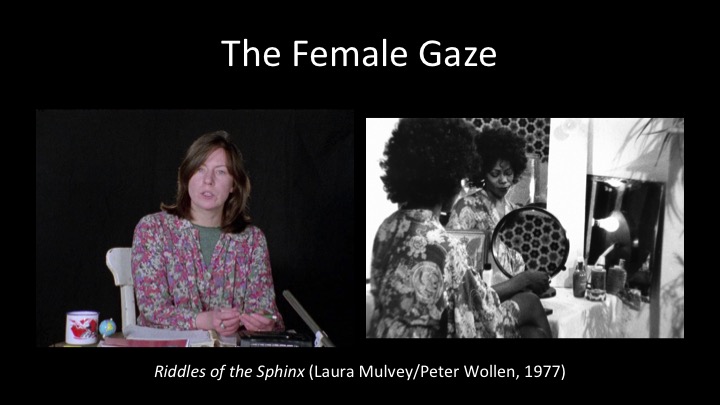

We’re screening Tapp und Tastkino along with Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s film RIDDLES OF THE SPHINX – which took up Mulvey’s revolutionary idea of ‘the female gaze,’ from her 1975 essay VISUAL PLEASURE AND NARRATIVE CINEMA, including a sequence in which the filmmaker herself addresses the camera to deliver a talk about the myth of Oedipus and the Sphinx, and the tour-de-force 360º single take sequence in which a lesbian couple discuss their dreams and desires, ending with a reflection of cinematographer Diana Tammes captured in one of the many mirrors on the walls. The décor and atmosphere of the scene is reminiscent of DAISIES’ bedroom scenes – there is even a floral motif on the wallpaper!

RIDDLES is one of several films on the REVOLT, SHE SAID tour that draw links between feminist film and feminist visual and performance art: in one scene, the couple watch a film by Mary Kelly that formed part of her infamous ICA installation POST PARTUM DOCUMENT, which focused on the early years of motherhood in graphic detail. We’re also screening Agnes Varda’s 1977 abortion rights musical ONE SINGS, THE OTHER DOESN’T, in which the female gaze is conveyed through the medium of absurdist performance art and feminist folk-pop protest songs.

And the three young Indigenous Australian women in artist Tracey Moffatt’s short NICE COLORED GIRLS take an approach to gender equality very similar to Maries 1 and 2, by rolling a middle aged white man who thinks he’s getting a date with them.

Nice Colored Girls was made in 1990, and it brings our tour right up to the emergence of the movement that, as Girish Shambu argues here, truly amplified and revelled in the radicalism of DAISIES: RIOT GRRRL, which came out of and brought together performance art, collage/montage and punk-influenced zine-making, and a vibrant, in-your-face, body-oriented feminism. Plus: a love of co-ordinated outfits and dance steps.

No-one embodied this more than Kathleen Hanna, lead singer of Bikini Kill, Julie Ruin and Le Tigre – whose co-ordinated primary-colour stage outfits and marching band-style steps have more than a whiff of DAISIES about them. Likewise, their video for HOT TOPIC, a song that –like this presentation – gives shout outs to feminist heroines, by drawing on the history of collage that DAISIES saluted and furthered. Feminist art has a long dual history: of cutting up heteropatriarchal sources, and of celebrating – by pasting in, lovingly – feminist forebears. It constantly reiterates the need both to bust things up and to rebuild them.

When teenage filmmaker Sadie Benning burst through a poster of Luke Perry in their 1992 film GIRL POWER, set to Bikini Kill songs, the explosive energy of radical feminist cinema returned to the screen after being somewhat dormant throughout the 1980s. Benning’s film, like Moffatt’s and like DAISIES, celebrates the explosive power of teenage grrrls, a power also seen in Chantal Akerman’s SAUTE MA VILLE, which opens our screening this evening. As Benning concludes their film: REVOLUTION GIRL STYLE NOW! We’re ready for the next wave…