By Jenny Clarke

I am currently living an unintentionally minimalist life in Edinburgh; I moved myself and some essentials up North and across the border, but I’ve yet to move the bulk of possessions here.

While this is a perfectly serviceable living arrangement, and somewhere I know Marie Kondo is smiling, it does mean that I have no more than 10 books within reach; and none of these provide the lockdown comfort I am seeking both for myself and to recommend to you. So instead I have decided to recommend the book I wish I had with me in this moment: Clare Hunter’s Threads of Life.

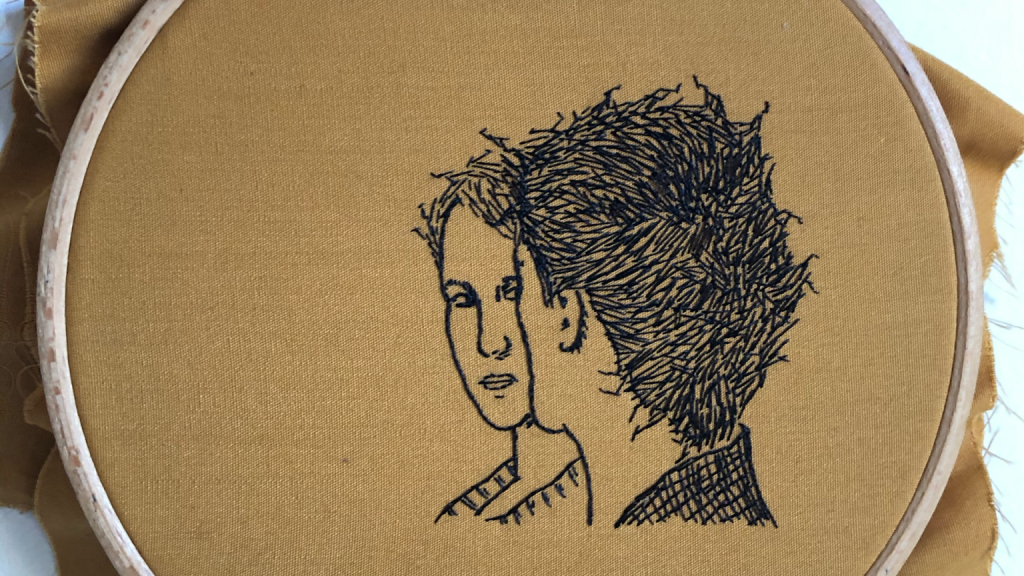

Outside of my film centred life I sew, I stitch, I embroider. I always have dabbled in stitches in some form, but it took hold as a full-blown hobby/passion/practice a handful of years ago and it has only grown since then. Embroidery is my main focus and, whether is it dumb gifts for friends or 9 month long projects, the act of sewing has brought me a great deal of pleasure.

However, I could never be satisfied with just stitching in a vacuum. I felt compelled to dig out the roots of the practice, contemplate the history, learn new stitches and forms of sewing; call it curiosity or call it extensive feminist training, I had to question and find connections within heritage and herstory. And I discovered that the field of writing on sewing is a strange and muddy one. It is growing and changing certainly, but there are a lot of canonical texts that need to be unpicked and questioned.

There are the tutorial books which offer stitches without context and beguile you with patterns and promises; the art theory and analysis which offers a feast of inspiring artistic practice, but occasionally get bogged down in the ‘artspeak’ neologisms and frustratingly reductive gender binary assumptions; the flat histories which talk so much about ‘fine young ladies’ and moral lessons that you want to throw your hoop out the window; and the feminist analysis which opens up the world of sewing a bit more, takes the history to task and rightly criticises the patriarchial hypocrisy which only allowed people who were raised female one form of creative expression and then laughed at it and demeaned it for centuries. I have consumed multiples of these and while each offered small moments of insight, none of them ever seem to get to the heart of sewing and they all seem to forget or ignore the effects of the act beyond the object produced.

And that is where Clare Hunter comes in, to collect together the scraps of these texts, darn the holes and patchwork together a fuller and more inviting history and contemplation of sewing. In my drafts of this piece I kept writing that Clare just gets it, but she does! She is a kindred spirit of sewing.

I had hopes for the book early on and those hopes only increased after reading the simple statement that opens the book and never fails to set my fingers tingling and reaching for my sewing box:

You cut a length of thread, knot one end and pull the other end through the eye of the needle. You take a piece of fabric and push your needle into one side of the cloth, then pull it out on the other until it reaches the knot. You leave space. You push your needle back through the fabric and pull it out on the other side. You continue until you have made a line, or a curve, or a wave of stitches. That is all there is: thread, needle, fabric and the patterns the thread makes. This is sewing.

I was convinced me and Clare were on the same page when she described her fury at the lack of information on display about the embroiderers who created the Bayeux Tapestry, at an exhibition of the work. She won my heart when she went in depth into areas of history that other authors have ignored, such as the Glasgow School of Arts female-led programme of teaching and developing sewing as an artform (and I knew it was true love when she took the opportunity to critique William Morris’ gendered bias against embroidery).

Threads of Life is not a year by year history; the chapters revolve around concepts such as: Community, Value, Captivity, Identity, and Power. Each begins with connections to Clare’s own practice and experiences, whether that is unearthing a heirloom quilt or recounting an experience sewing with mental health inpatients; she then links these moments out to historic examples and dives deep into them, uncovering more details than any other history of sewing I have read. Even when the histories are well known, I found Clare’s approach was able to draw out patterns and connections within these seemingly isolated histories. When discussing the altarpiece made for St. Paul’s Cathedral by injured WW1 soldiers, she draws out the therapeutic aspects of stitching; when addressing the AIDS quilt, she acknowledges the history of mourning textiles and stitching as protest. Reading these histories through Clare’s writing is illuminating, healing and more than once completely devastating.

Threads of Life is about all the forms of stitching: the big and bold banners made to be held aloft and shown to the world by trade unions, Suffragettes, and the women at Greenham Common; and also the small and quiet stitching: a message of support and love stitched into a quilt or names embroidered as an act of documentation. Clare fully acknowledges all the multiplicities of sewing: textiles as necessities and decoration, sewing as therapy and pastime, embroidery as an artform and as a record of forgotten lives, quilting as comfort and protest, weaving as industry and cultural identity. Threads of Life demonstrates the many many reasons why people throughout history have stitched, why they might have liked it or needed it, why we hold onto those textiles and why we continue to sew.

While I don’t have this book with me right now, you can be sure I have my needles, threads and fabric, so I intend to follow the paths of those who have wielded needles before me and stitch my way through it. As we all face more time tucked up in beds and on sofas, sandwiched between fabrics, it is a pretty good moment to contemplate the importance of these soft objects which we may occasionally take for granted. I recommend reading Threads of Lifeor, better yet, if you have the means, thread a needle and stitch something: a cuss word on your t-shirt, a patch for your jacket, or just mend that hole in your sock.