By Clara Bradbury-Rance

Clara’s book Lesbian Cinema After Queer Theory is forthcoming in paperback from Edinburgh University Press.

Netflix is available on… Netflix. Other streaming services are available.

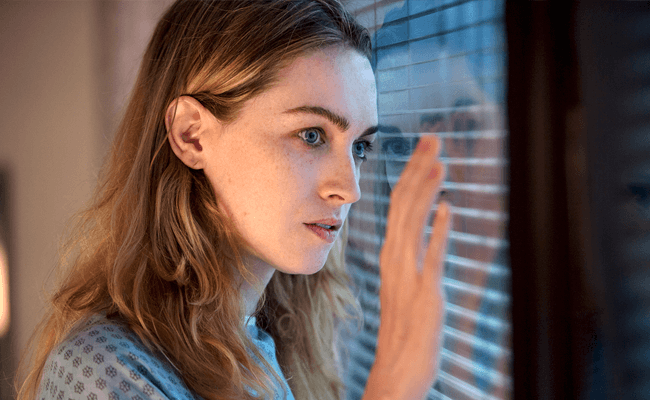

I land on a homepage designed to present to me a capsule of my interests. Row after row of brightly coloured thumbnails beckon my attention, apparently chosen especially for me. From the wildly general to the unnervingly specific, generic categories break the chaos into clusters: Phantom Thread, Below Her Mouth, Sense and Sensibility. The idiosyncrasies are as disconcerting as they are amusing; they are, perhaps, even pleasurable. From wishful thinking to period love affair via conflicted voyeurism: Netflix promises a datafication of my queer tastes, in all their ambiguity, irreverence and promiscuity. But I am unlikely to find this particular sequence of landing cards again. Soon enough, a new set of recommendations will be generated in anticipation of my interest. Yesterday’s headline act, automatically and noisily trailed at the top of the page: the latest obnoxious, heteronormative, utterly addictive dating show. Today’s: a documentary about a hardcore gay book and video store.

When evening comes, I can’t even sit still for 90 minutes. Instead, I’m jolting from one streaming service to another, unfocused and easily distractible, the perfect social media candidate. BFI Player doesn’t let you resume watching a film at the same point where you left off. The erstwhile cinema purist in me (where erstwhile = pre-lockdown) can see why; films aren’t made to watch in short instalments. Now, I find myself snapping photos of the timecode in order to remember where I’ve paused a film, at best making it to the full hour mark.

Unlike the BFI, Netflix has built an empire on knowing audiences won’t finish a whole film in one sitting. It’s not a replacement for the cinema, it’s something else entirely. Algorithmic meddling encourages a promiscuous spectatorship.“Recommendations” are designed not to enhanceour cultural attachments – the kind this Culture Club celebrates so beautifully – but to forestall them. While our DVD libraries are archives of past viewing pleasures and sustained commitments, our Netflix watchlists will contract as catalogues move on, will change entirely when we enter a new region, won’t even recommend the same film to us once we’ve seen it already. Repeated viewing (aka commitment, aka obsession, aka virtual queer community) was never part of the business plan. Queer feminist practices of citation have thrived on recommendation as repetition as recognition. What form do they take now?

But perhaps there are pleasures here too. Not in spite of how infuriatingly inaccurate Netflix’s recommendations can sometimes be, but because of it. Plastered across its website is a promise: “to bring unique joy to each member”. But we all know, by now, that Netflix is very unlikely to have exactly what we want. The company’s researchers admit that only 13% of searches are successful in delivering a “perfect match”. So we subscribe for the sake of Sex Education or Queer Eye and then stick around, see what comes up next. We route our browsing via “LGBTQ”, ever the generic outlier: okay, Netflix, get your recommendations right or wrong, but at least make them gay. Even then, we’re unlikely to find what we think we’re looking for.

But what do we think we’re looking for, exactly? A well-documented history of cinematic invisibility can look more like visibility with a twist, if you look hard enough. Judith Mayne called it “finding the lesbians”; Patricia White showed us that lesbians might not have been “invited” to the party but they’re sure as hell still there. In other words, take what you can get – always a hallmark of queer viewing practices (just watch Susie Bright watch Joan Crawford with delicious anticipation). Yes, times have changed since The Celluloid Closet. Now we’re told we can just seek evidence of queerness on-screen in a character, couple, sex scene – or better yet in a screenwriter, director, star. But “evidence” can take different forms, as queer film and television critics were telling us long before The L Word and The Kids Are All Right. For me, thinking about lesbian cinema through the provocations and exhilarations of queer theory expands our conception of desire while making lesbian legibility harder than ever to pin down.

Netflix algorithms can produce uncomfortable and uncanny juxtapositions that toy with the histories of citation marginalised communities have built up to confront the paradigms of dominant culture. But maybe that’s the provocative fun of it. Like it or not, queer culture often comes to function as a tactic of citation. Recommendations can act as mere virtue signalling, as repetitions of appropriate behaviour. Trust me, as a lesbian film scholar routinely asked what I think of Blue Is the Warmest Colour. But fantasies of desire don’t always align with identity. And maybe, the work done by algorithms inadvertently replicates the ambivalent moves of identification and desire that we normally locate in our psychic lives. A recommendation for Dirty Dancing doesn’t fall outside of the remit of my lesbian viewing pleasures; it’s one of the best coming-out movies of all time, and I’m forever indebted to Swayze as style icon.

You won’t find it listed under the “LGBTQ+” genre though. My talent for decoding goes under the algorithmic radar, it seems. I’m both delighted that not all my subversive identifications can be taxonomized … and unnerved that Netflix doesn’t explicitly recognise viewing communities founded on the pleasures of subtext. Here’s queer viewing in a nutshell. Don’t put me in the corner but let me visit every now and then.