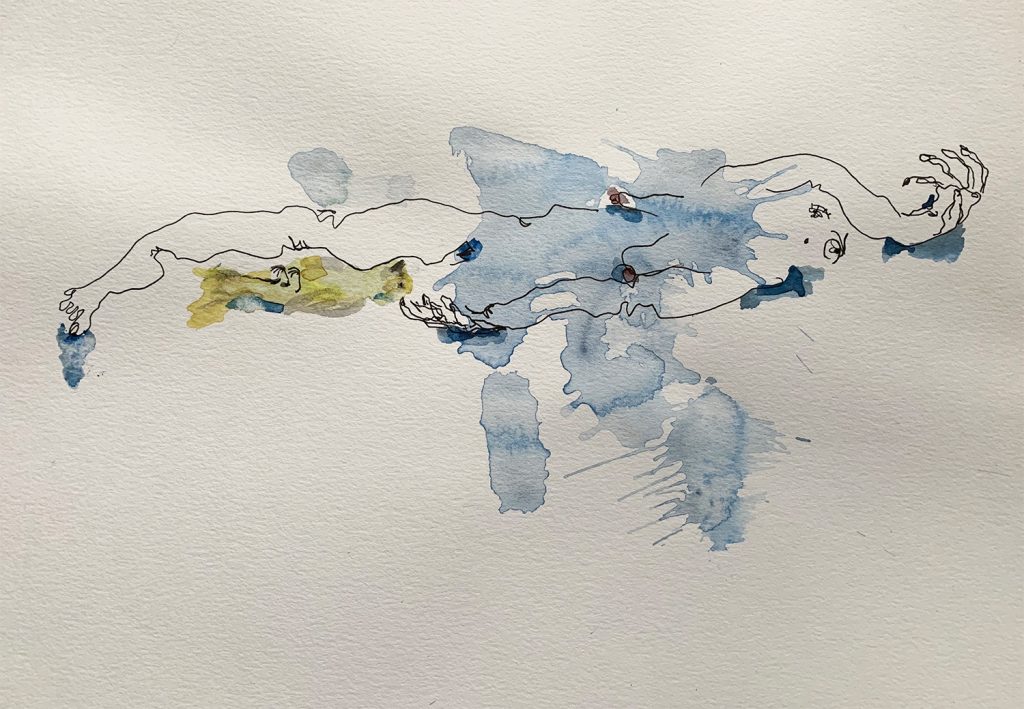

By Dima Mikhayel Matta

In the Dream House is published by Graywolf Press in the US and Serpent’s Tail in the UK. UK readers can order it in hardback (£14.99), or pre-order the paperback (£9.99, published 1 Oct 2020) at a 10% discount, from Burley Fisher Books.

Library card holders can check Overdrive to see whether your library has an ebook or audiobook (read by the author) available for loan.

CN: both the book and the post concern intimate partner abuse in queer relationships.

An explosion took place in Beirut between the time of writing and publishing this piece, I don’t know what sustains me now

“It gets heavy when you’re halfway through the book.”1

“If you need this book, it is for you.”2

“Where the fuck were you?”3

“Here you are learning that lesbian relationships are, somehow, different – more intense and beautiful but also more painful and volatile, because women are all of these things too.”4

“I never read prologues. I find them tedious. If what the author has to say is so important, why relegate it to the paratext? What are they trying to hide?”5

Dima’s essay as prologue for a play not yet finished

This is supposed to be an essay about a work of art that sustained me. It is important for me to write that I am fine now. A few years later, another partner yelled at me for having a panic attack. She accused me of being negative and wanted to leave me stranded in a foreign city I spent my rent money to fly to so I could meet her. I didn’t break up with her right away. It took me time, but I did.

To sustain means to hold from below, to keep from falling (apart). This is what In the Dream House did for me. Then, I write on.

- My friend warned me when she got me the book. I kept it on a table for two weeks before I picked it up. Five days so that if it had traces of Covid on it, it would die. Nine days to gather the courage. The book she was talking about is Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House. She was wrong. I was scared as soon as I opened the book. There isn’t a lot of literature on intimate partner violence in queer relationships. For a long time, we didn’t think it even happened. For a long time, if there was no physical violence, we did not consider it abuse. We would say, “it’s just intense, that’s how much we love each other.”

- The dedication page reads. I needed this book for so many reasons. The lockdown in Lebanon began at the end of February. March. April. May. I couldn’t finish a single book. I would pick some up, read a few pages, then leave them on my nightstand to gather dust. Unfulfilled promises. Meanwhile, Lebanon is going through an economic collapse. The price of everything tripled. People are starting to starve. Newspapers are predicting a famine as devastating as the one we experienced in 1915 that supposedly killed half of the population. This doesn’t seem relevant right now, in an article about what sustained me during the pandemic, but it’s just to say, or rather, to say, I have not witnessed darker times in this country. The last thing I should be reading is a book about intimate partner violence. I finished the book in three days. We were getting two hours of electricity a day at that point, so at night, I would drain my phone’s battery by turning on its flashlight, resting the phone on my chest, and read. I couldn’t put it down. I felt like an artist who just received fresh paint and new brushes. I wanted to eat her words. She is a writer’s writer. I marveled at her sentences, “I see what you’re doing here, it’s beautiful. Thank you.”

- Opening the book, I knew. The relationship will start out beautifully. It will be fun and the narrator will feel understood and seen by her new partner. It will be passionate. Intense. Then, a sentence. One sentence. A gesture. When Carmen doesn’t answer her phone for a couple of hours, her girlfriend yells, “where the fuck were you?” and she brushes away Carmen’s explanation by calling her selfish and inconsiderate. On a trip, her girlfriend puts her hand around her arm “and her fingers tighten […] Her grip goes hard, begins to hurt.” And later, no explanation, just a one word apology. For me, the sentence was “you’re mine.” Said with teeth clenched. A month later, we fight, she grabs my wrists and tightens her grip until they hurt. Then she falls asleep and I sit on the edge of the bed wondering what I did wrong.

- Machado tells herself. Otherwise, it means that we weren’t smart enough to know better.

- Machado writes. Then you turn the page, and you find her prologue. When I closed the book, I decided to start writing my second play. About a queer woman in an abusive relationship, here, in Beirut. I know this has happened to me and many of my queer friends, but we almost never talk about it. It’s a small queer community here, we’re afraid of the person finding out, we’re afraid of being judged by others and told we’re being dramatic, it couldn’t have been that bad. As queer people, we know how to read and interpret paratexts very well, either because this is where so many of us reside, in the margin, or because we examine them closely for signs of danger or violence. The main text rarely belongs to us.