By Jack Thompson

Rebel Dykes premiered at BFI Flare 2021, and will be distributed in the UK and Ireland by Bohemia Media.

You can follow @RebelDykes on Twitter for updates on how to see the film. In the meantime, catch the filmmakers and rebel dyke Atalanta Kernick in conversation with Flare programmers Jay Bernard and Tara Brown here.

I

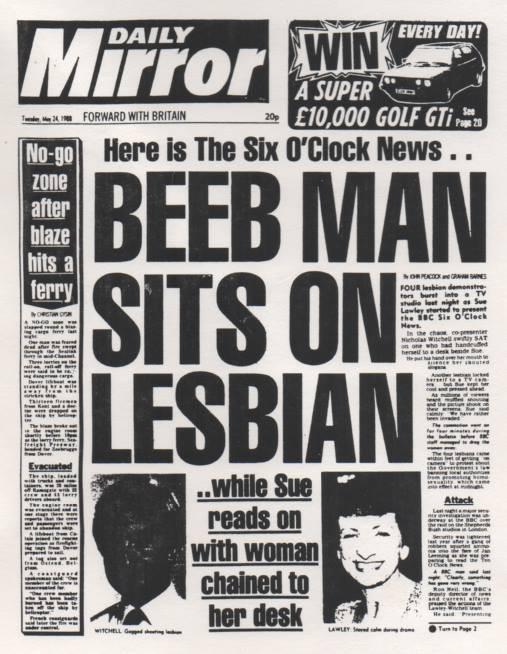

In 1988 a headline ran in the UK news: Beeb Man Sits on Lesbian. I was four years old. I was living in a small house on a dead-end road in North Yorkshire, with my parents and younger brother, one year away from starting school. The comedic headline referred to a gutsy, brilliant piece of direct action in which a group of dykes infiltrated the BBC building and chained themselves to news desks to protest Section 28. During the 6 o’clock news on 23 May 1988, broadcasters Sue Lawley and Nicholas Witchell were interrupted by queers padlocked to their desks shouting Stop the Clause and Stop Section 28. I have no idea whether my parents saw this, or whether they had any idea about the protests happening in London.

But Section 28 came into effect in Thatcher’s Britain in May 1988, and it lasted 15 years – ending the year after I finished my A-Levels, the year after I left my small Yorkshire town for a bigger Yorkshire city. My entire school life was spent under Section 28, which might go some ways towards explaining why I had no idea that there were gangs of dykes chaining themselves to news desks, starting SM clubs, protesting nuclear armament, fucking each other in public, playing in bands. Section 28 was so effective that I, a closeted adolescent dyke, didn’t even know it existed until it was over.

II

I had a visceral reaction to Rebel Dykes, a long-awaited documentary directed by Harri Shanahan and Sîan Williams, and produced by Siobhan Fahey, about a group of punk dykes in 80s London. I think about how altered my life, and the life of many queers my age, might have been had we had ready access to this recent history as teens, to the fact rebel dykes existed in a tangible sense, to the notion we’d grow wanting to create chaos and fight and shout and fuck and that it was okay to want to do so – it was (mostly) healthy to want to do so.

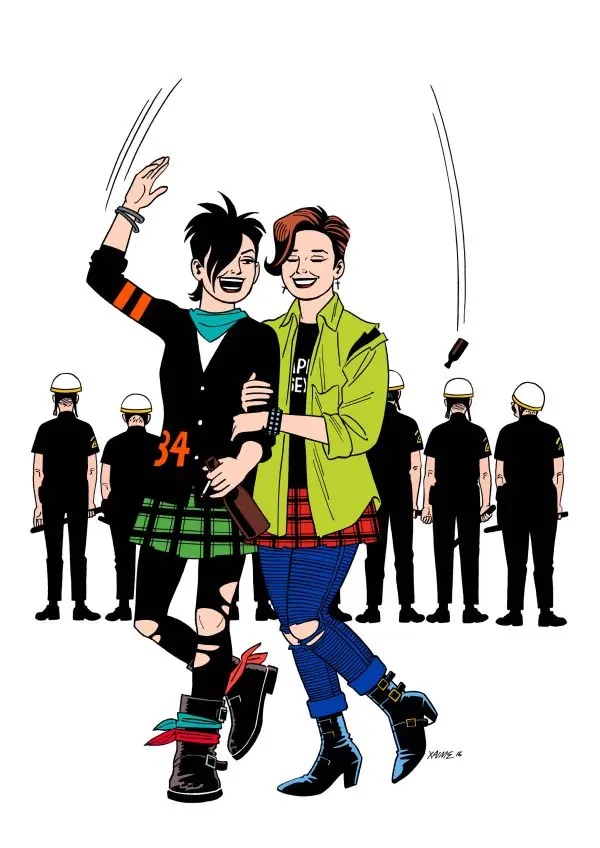

When I first moved to London in 2008 I started reading Jaime Hernandez’s Love & Rockets comics and fell in love with Hopey Glass, a riotous, openly queer punk with excellent hair and a love of leather boots and booze. After spending time with lesbians I liked very much but felt apart from, Hopey was the closest I had come at that point to being able to define my sexuality, my gender, my restlessness. Like Hopey, I wanted to be drunk constantly, to watch bands, to stay up all night fucking. I wanted to have Hopey’s unwavering confidence. The fact she was created by a cisgender straight man did not escape me, but Hopey was a real lifesaver for me in so many ways. And years later, watching Rebel Dykes, here were our own homegrown versions of Hopey, same clothes, same haircuts, same radical (mis)behaviours.

III

Rebel Dykes has been years in the making; I saw a preview at BFI Flare in 2016. The energy in the screening was wild and beautiful and it was joyful to be there amongst so many older dykes, still wearing leather, still unruly as anything. The atmosphere was electric; it was the same comfortable anarchy that pervades the documentary: you look at a gang of dykes in leather and see trouble, I look at a gang of dykes in leather and see safety.

I mention the screening because Rebel Dykes is a film about togetherness, about chosen family. It follows a group of queers who meet at the women’s nuclear protest camp at Greenham Common. Someone should make a spinoff film about Greenham, which consisted of a number of different camps of women and seems like the best lesbian party of all time. [CdF note: check our Bringing Greenham Home programme for more on this!] There was a camp for musicians, a camp for separatists, a camp for punks. Little dykes were spending weekends at Greenham and then going home Sunday night for school on Monday. There was witchy sex in misty woodland. There was a lot of drinking and mischief. From this environment evolved queer family in the form of rebel dykes, a subculture rallying against Thatcherism, homophobia, racism, gender inequality, misogyny, warfare – and having a lot of anarchic fun.

Watching the preview surrounded by the dykes that were part of it, it was plain how close they’ve remained, how they’re family, despite having gone separate ways. Thinking about that screening now, from the anxious end of another long coronavirus lockdown, gives me a little gut twist; so many of us have been separated from our queer family for so long now, have gone through (and are still going though) not only a pandemic but the horror of virulent transphobia, institutional racism, sexual violence, abuse of police power. We’ve watched this horror unfold from screens in our individual homes, the most vulnerable among us unable to join protests, the protests that do happen broken up with violence. And we’re not able to come together in pubs or kitchens or clubs in the same way we would have pre-pandemic, to decompress and find comfort in one another. It’s strange watching a film so much about togetherness, when togetherness feels so alien.

IIII

I moved to London in 2007, a few years before all the bars started shutting down. I got here in time for the last gasps of the Joiners, the George and Dragon, the Nelson’s Head, First Out, Glass Bar, Trash Palace. I was working as a bookseller in Foyles by day and drinking pints in gay pubs by night and it was among the happiest I have ever been.

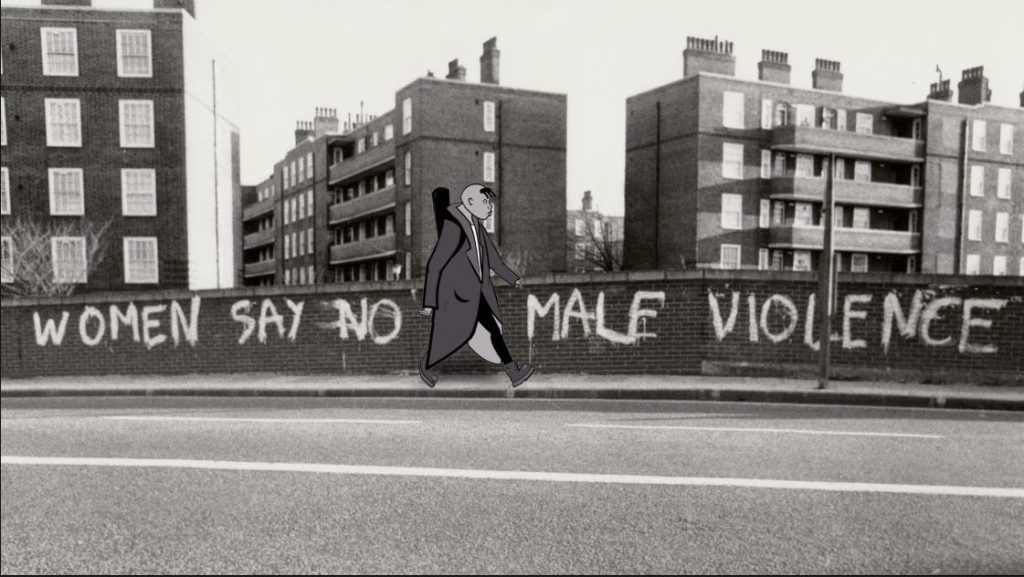

I am constantly lamenting the death of queer spaces in London – in my imagination, there was a queer bar on every corner during the 80s and 90s, so I was surprised to hear Debbie Smith appear on screen near the beginning of the film and say there weren’t many places for lesbians to go then. In Rebel Dykes there wasn’t enough footage for a feature length documentary, so Shanahan and Williams filled out the gaps with punky, sketchy animation. One of the parts that plays in my head is an animated Debbie Smith walking past an animated council block with a guitar slung over her shoulder and the voiceover: “It was a great time, and a terrible time, to be young and queer in London.” It’s a perfect soundbite for the film, for the evolution of a subculture that sprung from this fortress of dykes built against the horrors of the mainstream. Another great soundbite: we were a community because there were so many laws written against us.

When Fisch appears on screen, a then-rebel dyke, now-drag king, she talks about arriving in London and feeling isolated, feeling like the only lesbian in the city. There was a phoneline, the Lesbian Line, you could call and find out where the dyke bars were. At that time there was Gateways, a butch-femme bar, and the Kenrick Society, which Debbie Smith describes as a place for rich lesbians in west London. The rebel dykes were young, punk, poor, and working class. Some were black, some were trans – they existed outside the realm of mainstream gay and lesbian culture, from which they felt ostracized. And London was dirtier and more dangerous then, and it was harder to get around; throughout the film the dykes talk about waiting until dark to go out, about being constantly at risk of being bashed, which many were, and often.

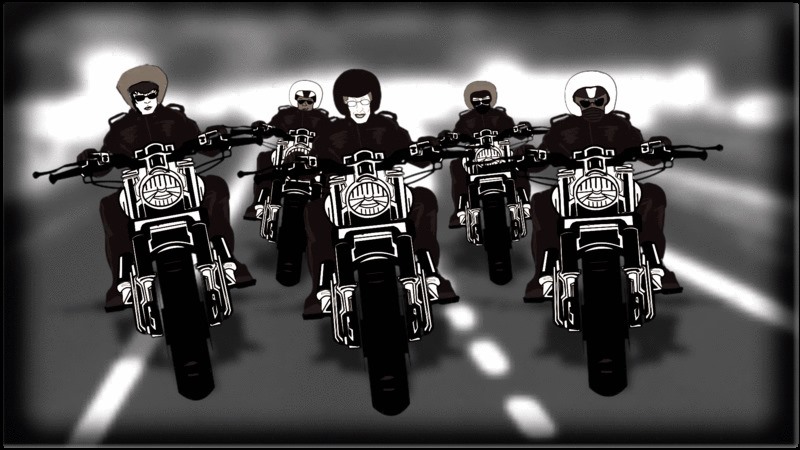

It’s easy to see how the rebel dykes came out of this climate to form a culture of incendiary, recalcitrant gender non-conforming queers who were determined to carve out their own place in London. They squatted buildings in Brixton, took what they needed, slept with each other, made art, got high, formed motorcycle gangs, started bands, kept pets. As Baya, a dyke who came to London from West Berlin, says at one point in the film, it was our own little fantasy world.

I’ve always loved the idea of queers making space for themselves in a city and culture that wants to reject them, both culturally and physically. The rebel dykes made London’s streets, empty buildings, and dark underpasses their own playground. Watching the film brought to mind Michelle Tea’s phenomenal essay HAGS in Your Face, about a similarly anarchic group of butch dykes in 90s San Francisco who called themselves HAGS, who ran around doing petty crime and fucking each other and riding motorcycles and wearing leather. In an interview with Dazed, Tea writes:

they represented something to me when I moved to San Francisco, they solidified that this was the place that it was a city that could hold these beautiful raw ruffians that were living outside of the law, a rational response to a culture that hated queer people, women, gender variant people, poor people.

The HAGS and rebel dykes occupy a similar space in my imagination. Being a queer in London, I’ve met a few of the rebel dykes in person, either through my partner or at clubs, screenings, book events. Some are still in London filling the same queer spaces, despite those spaces looking different now. I wonder if there are still HAGS riding around San Francisco – although their story has a tragic ending; many died from bad heroin. From our queer present, it’s a privilege and a thrill to have accounts of those who came before us; the energy you get from watching Rebel Dykes or reading HAGS in Your Face is the same; complete awe, total infatuation, a desire to carry some of what they stood for into our queer futures.

V

The thing I enjoyed most about Rebel Dykes was how horny it is. Here was a group of hot androgynous young queers who all fancied each other and who wanted to be fucking, all of the time. We need more of this – so much weight is given to the sexuality of gay men, but hardly ever to that of dykes, and what a waste that is; likewise, that trans people are all too often omitted from our conversations and archives of eroticism and desire.

Chain Reaction was a club night that started in 1987 at the long-gone Market Tavern in Vauxhall. It was started by rebel dykes, by a dyke called Seija who had run a club in Finland that was a mixture of art, porn, and SM. Chain Reaction was by all accounts an SM dyke club, with cabaret, live sex, mud wrestling, leather, chains and whips. Unlike a lot of lesbian spaces, it was trans-inclusive, and it looked plain fun and completely playful, a group of leather-wearing young dykes wrestling in spaghetti hoops, tying each other up and fucking each other. In the film, a rebel dyke known then as ‘Jane, Queen of Pain’ spoke about how she was ashamed of wanting sex all the time until Chain Reaction, through which she learned to own and explore her sexuality. Jane speaks about it being a safe place to fuck, about how the SM element for her was cathartic, a way of taking the power away from the violence of the straight world: “Somehow we felt much more like we could survive a beating.”

Chain Reaction was stormed by a group of people in balaclavas with crowbars, axes, sticks. They smashed glasses, hit dykes, trashed the bar. They turned out to be feminists protesting violence against women with violence against women. Debbie Smith calls them WAVAR – Women Against Violence Against Women. Someone else calls them Lesbians Against Sadomasochism. They were a group of outraged feminists who thought Chain Reaction was misogynist, that it was anti-feminist, that it was mirroring domestic abuse. They made flyers that asked ‘is there a man in your head?’

The whole affair sparked a culture war with sex-positive rebel dykes on one side and lesbian feminists on the other. The rhetoric of these feminist groups so closely mirrors that used by TERFs that it’s hard not to wonder whether these are the same people. Maybe they are; Siobhan Fahey, the film’s producer, was one of the rebel dykes at Chain Reaction and says in an interview with Vice that

They were really extreme and really annoying. I think, in a way, they became what you call TERFs [trans-exclusionary radical feminists] today. The philosophers they based their ideas on were some of the same people, like Sheila Jeffreys and, later, Julie Bindel. Trans women are the enemy now, but we were the enemy then.

As an aside, the UK’s first lesbian sex toy mail order company, started by Stonewall co-founder Lisa Power, named their smallest and most ineffective dildo Sheila.

The anti-sex position of the feminists who smashed up Chain Reaction is the same as TERF thinking in that it’s plain horrible, regressive, hateful, violent, and illogical. It’s also so lacking and unimaginative that the cringing is intense. We watch attacks on trans people and their allies daily on Twitter, see TERFs with enormous followings consistently platformed in the media, hear about the truly damaging effects this has on trans youth.

The problem is so pervasive that we, as queer and trans publishers, writers, artists, and activists are having to find new ways to protect ourselves against it; in a digital world, how do we stay connected while also pulling back? The Chain Reaction debacle feels particularly prescient, born from the same rift within feminism we’re battling today. Although now we have the internet, and Twitter, and there are hundreds of different methods of attack.

As Roz Kaveney puts it: you can’t tell people who to have sex with, or how to have sex. As a dyke club that scandalized the mainstream and made headlines in the 80s, you can’t help but wonder what the Chain Reaction controversy might look like today, on the internet. It feels nightmarish. But looking back to a world pre-internet, it’s wildly exciting to watch queers own their sex, play with their gender and put their trust so wholly in one another while having access to a queer space that made it possible. Another soundbite from Fisch: we weren’t lesbians, we were dykes! We wanted to be sexual people.

v1

I co-run Cipher Press, which publishes queer and trans books, and with my publisher’s hat on I am very into the ways information has been printed and distributed to the queer community over time, and in the ways queer publications have been archived. Rebel Dykes is a documentary about dykes in the 80s, a decade when booksellers were fearful of the Obscene Publications Act. In 1984 Gay’s the Word was raided as part of Operation Tiger by police and customs who seized over 2000 imported books they deemed obscene. Four years later, Section 28 was signed into being. As far as the straight world was concerned, Chain Reaction and the rebel dykes were about as obscene as it gets.

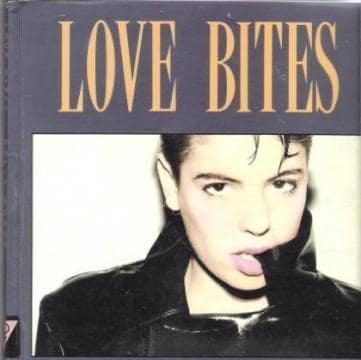

But their experiences were documented, most notably in the photography collection Love Bites by photographer Del LaGrace Volcano, who says:

Rather than bring my camera into the club, a sacred and profane space, we often went our into the world and created public spectacles of ourselves… we posed and performed for each other… I think it gave us all a sense of satisfaction to see the looks on some faces when confronted by two dozen dykes in leathers looking fierce and fabulous.

Although some mainstream bookshops did stock Love Bites, heavily shrink-wrapped, queer bookshops like Silver Moon and Gay’s the Word did not; they feared it would make them susceptible to prosecution. A happy addition to Rebel Dykes was an appearance from the wonderful Jim McSweeney, bookshop manager at Gays the Word. Back then, stocking a book like Love Bites would perhaps have made an already vulnerable queer space even more so.

Rebel Dykes also pays homage to Quim, a magazine ‘for dykes of all sexual persuasions.’ Quim was a sex-positive lesbian magazine that ran for five years between 1989 and 1995 and followed US women’s erotica magazine On Our Backs. Quim was publishing as the rebel dykes were starting to separate – many of them leaving London, tired of the partying and/or the constant fights within feminism – we can think of it as an archive of the rebel dykes’ legacy, a continuing document of a culture they helped create.

If we want to look at queer erotica now, we can open Google or Instagram, but publications like Love Bites and Quim linked queers living outside of the world of the rebel dykes to their own sexualities and were vital lifelines for anyone who didn’t sit comfortably inside the lesbian and gay mainstream.

VII

Towards the late 80s the rebel dykes were fighting AIDS with Act Up and protesting Section 28 by abseiling into parliament and chaining themselves to news desks. Rebel Dykes is the archive of a constant, endless narrative of necessary fights, it’s about the resilience and playfulness of a group of queers who felt ostracized from both the straight world and the mainstream gay and lesbian world.

Watching Rebel Dykes, you can’t help but draw comparisons to the queer landscape we know now, examining what we’re clinging on to from that time and what we’ve forgotten or thrown away, what we’ve lost. Post-internet it’s a very different world, with very different forms of access and acceptance. Although there are still pockets of queer family all over, how effective are these family structures in creating spaces for outsiders and rebels, when the mainstream is consistently trying to swallow so much of our queer culture. As Lisa Power says towards the end of the documentary: “We’ve gone so far into the mainstream now that we’re losing all our sharp edges.”

Are we losing our ability to be rebels? It wouldn’t be fair to say yes entirely; organisations like the Outside Project and Queer House Party are doing incredible work in keeping our community connected and campaigning, and direct action group Sisters Uncut are bringing queer and trans people together through their activism. But, whether because of the ‘new normal’ evolving from the pandemic, or the fact so much of our lives are now lived online, we’re adjusting to new types of togetherness, new ways of protest, different structures for our chosen family and communities, and it feels like a very different world. Perhaps it’s a lack of the playfulness that comes with taking up, and taking over, a physical space, of using our queer bodies to create mischief, fill rooms, crowd public spaces.

The rebel dykes laid the foundations for so much of our queer culture. After rebel dykes came the Lesbian Avengers in the 90s, Riot Grrrl and Queercore music, Queer Mutiny. It is thanks to them we can be a part of a queer culture that fits us. After growing up under Section 28, it’s a privilege to have access to this film and I tip my (leather) cap to Harri Shanahan, Sîan Williams, and Siobhan Fahey for making such a playful, wild, sexy, and important documentary.

Watch the trailer here: