Filmmaker Maz Murray / @maz_murray and writer D Mortimer / @fragile_masculinity in conversation about their recent visual/performance works Thigh Rise [watch it on Girls on Film] and Between the Stacks – the hybrid play/text – accompanied by an introduction by Forest Greenway (they/them), a writer and bookseller based in London.

Lust and loss is a part of everyday experience — The way it is everything at once, you don’t get to choose unless you choose everything.

Nostalgia increases with each misrepresentation, marking the death of the imagination, increasing misrepresentation, but what about when it’s a nostalgia for death? Museums filled with the nostalgia of the gentrifiers: remember when death was all we had — Oh!, those were the days. Is there a difference between nostalgia and gentrification, or are they two elements of the same process of cultural erasure?

—Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, The Freezer Door (Semiotext(e), 2020), 146.

I’m thinking about bodies in spaces and bodies in language. I’m thinking about the failure of language to touch the intimacy of our bodies as they grow to defy expression as in the work of Maz Murray and D Mortimer. Particularly their respective works Thigh Rise (2025) and Between the Stacks (2025).

If nostalgia and gentrification are two sides of the same coin, there is always some small sadness in what is lost. I find the meeting of these two forces as being analogous to queer experience in the flight from the heteronormative principles of living.

Why then is nostalgia often associated with a pleasant sensation of reminiscence. I despise nostalgia in all its forms. Possibly because all I look back on is struggle. But of course within that landscape of the past there were love stories, there was hope. Albeit often embodied against stacks of odds. In the practice of living queer lives in a system that was not built for us we march on always under the spectre of those that came before us. It seems to me a sort of faulty blueprint of a potential life as defined by a culture that was never our path to tread. The built environment mimics the words we use to describe our bodies and our ways of loving each other in their failure to rise up and meet our truth and so we hack the words to express our gender. We hack our environments to express our sexualities all the while trying to liberate ourselves from the conditioning of early life.

In the practice of living queer lives in a system that was not built for us we march on always under the spectre of those that came before us and the oppression that has shaped our movement amongst buildings. However there always remains the reality of how we exist now. Richly complicated and waiting to be expressed. A possibility and – I might argue – an invitation. Meeting this invitation are these two artists. Perhaps nostalgia, fetish and absurdity can offer us the tools by which we draw a line around the negative shape of who we are in the present moment? To try and lean in a little bit closer to who we are in our relationships to one another and to ourselves: to hack the blueprint.

— Forest Greenaway

*

D Mortimer: Hey Maz, I love Thigh Rise, the comedy and absurdity of it. What were you doing when you wrote it? And what gave you the idea?

Maz Murray: It was covid lockdown, of course, and I just had this vision of the boot — the thigh high boot that looks like a tower block. Then came this concept of boot buildings being a reaction to the housing crisis, with giants wearing them to make a bit of extra cash, making it easier to move buildings around. An extreme version of how it can feel to live near loads of new developments, like the world’s being rearranged around you. I was thinking about films where there’s this big conspiratorial revelation about the nature of society and then imagining if that actually happened to me I’d still need to get up in the morning and make rent and go to work – what would actually change? Like if I found out I lived in a boot?

I remember we all had a studio together when you were building the set and thinking how genius it was when you told me your plans for the film. Like the old woman who lived in a shoe or swallowed a fly. I love the size play of it and taking a trans in-joke to its hilarious conclusion (human suppository spoiler). Would you talk a bit about the visual gags in Thigh Rise? And maybe in your other work too!

Yes, I love the way you phrase it: taking this trans in-joke – t4t height difference – to a certain necessary conclusion. I love a visual gag, I love slapstick, I love simple silly humour and I think applying that to transness feels really freeing. I find myself returning to joke archetypes – “Who’s on first?” in Principal Boy; the cartoonish visual of being literally thrown out of a club in Poppets.

The big gag (pun intended?) of Thigh Rise is the sex scene at the end, which is so simple and silly and base but to me quite beautiful. The practicality is first brought up in a slightly mean way: Paul, the tiny guy, is mocked by Grace’s giant boyfriend who questions how they would be able to have sex. Which is not very imaginative of him, but honestly a fair question if we’re taking this fantasy concept and trying to apply it to real life concerns. This is also the moment where the trans allegory is made explicit in a more emotional register – like, this is a prurient thing someone would say to a straight trans couple. So Craig, the giant guy, says it as a joke, which leads to a slightly tragic moment. He’s punctured the fantasy and neither Grace nor Paul are confident enough to back themselves – yet.

To rebuke Craig we then need to take their romance seriously at the end and show them having sex – I didn’t want it to be too chaste and fairytale. So we shot this scene where Paul is supposed to be inside her ass, fucking her with his body: we used a pink plastic tunnel and I think it works pretty well. It was also important to me that he was the top in the dynamic as much as physically possible. And in that way, their relationship makes perfect sense. He’s exactly the right size. Then if you watch it again, you’d perhaps be mindful that when he’s standing on her hand it’s quite evident how he could be making himself useful later on.

In Forest’s introduction, they mention how the

built environment mimics the words we use to describe our bodies and our ways of loving each other in their failure to rise up and meet our truth and so we hack the words to express our gender. We hack our environments to express our sexualities all the while trying to liberate ourselves from the conditioning of early life.

In both our works (TR, BTS) there’s improvised ways of living and making work for trans people in the city. You’ve literally melded the building and the body with your house boots. (Boots the house down.) Do you see a correlation between hacking the body and hacking the city in the film/ in trans life?

I might try and answer these thoughts by looking at the difference between Paul and Grace, the two main characters in Thigh Rise. Paul, the tiny guy, is a trans guy who’s kind of done everything ‘right’: I imagine him as mostly stealth, he talks about getting this part ownership flat, the closest thing to property ownership he can manage; he’s paying the mortgage, he’s not getting out much. The set I made for Paul’s neighbourhood is analogous to parts of London that are economically deprived and ethnically diverse where private new build developments just get thrown up without any infrastructure to support this influx of people, people who are usually whiter and more middle class than those who live in that area. Being trans doesn’t necessarily preclude him from being part of this influx – progress! Grace, the giant, is a trans woman who’s hacking her way through the city by wearing the boot buildings. She’s also implied to be a sex worker and generally involved in informal economies, which is pretty common for trans people, and speaks to how the foundations of ‘the city’ are built on sex work, informal economies and the underclass.

At the beginning of the film, Paul is very unhappy and, although I try not to hammer it in too hard, he’s sitting on the ledge of his window because he’s contemplating suicide. Trying to fit into the correct way to live, despite transgressing this path by being trans, is not working out for him. Suicide is such a trope in trans stories (fair enough – the stats aren’t great) so I was interested in deploying it in a slapstick way – a bit like in Cracking Up, the Jerry Lewis film. This also gets the topic out of the way early and doesn’t link suicidality to like – the horrors of trans life – but the horrors of an empty assimilationist life.

In casting, I chose Silver and Alexis because they were great for the roles, have chemistry and look good together. I wanted to create a sort of trans Love Island couple, to veer away from ‘queer aesthetics’, which meant Silver had to dye his hair back brown and cover their they/them knuckle tatts. And then I also wanted to contend with the reality of Silver being white and Alexis being mixed Black, and her presence signalling an archetype of the ‘Black Trans Woman’, who is so often turned into a political symbol, both in her absence and in her presence. So we have these two symbols – the white trans guy who’s stealth and has achieved a level of economic stability and normality, and the Black trans woman who’s engaging in informal economies. These symbols exist politically and academically and in annoying films by cis people. It’s probably about as subtle as a hammer, but I was operating in this B movie register, which perhaps allows for that.

When I thought about bringing these two characters together, I was reminded of a conversation I overheard in the waiting room of 56 Dean Street. I was sat a bit away from this group of trans women, we were all waiting to get our bloods done, we were all self-medding I can assume. And the women, who seemed to mostly be from Latin America and had a very femme, done-up, doll aesthetic in the earlier pre-T shirt sense, were in real time discovering the concept of trans men. I heard one woman describing testosterone replacement therapy, another explaining top surgery and another explaining bottom surgery. Then the last woman said: ‘Well, where are they?!’

To me, it showed how we can still live such parallel lives in the city – often along lines of gender, class, race and migration – within something that could be described as ‘the trans community’. We were brought into the same space by a shared engagement with informal economies: use of black or grey market hormones. With Thigh Rise, I didn’t want to go too naive ‘love conquers all’ within this dynamic, so there’s a fake-out ending where we get a happy ever after, and then we get a joke about trans guys being gay and both characters kind of returning to their initial economic positions. But then the women get to destroy the city that’s been built on their backs legs.

When we were getting kicked out of our studio, the security guard of the building couldn’t tell us all apart (three white trans mascs roughly the same age) which led to some absurd run ins. Misrecognition is a hallmark of farce, as are entrances and exits. I feel these feature largely in both our pieces. And contribute to the surreal, off-key nature of the works. I actually thought of you to direct the film part of Between the Stacks because of this city surrealness that’s in Between the Stacks too and is so potent in your work.

That was so funny (sad). I remember it well: I got locked in the studio because I didn’t know the opening times (duh) so I came downstairs and the whole building was locked. I was spooked. So I had to go through this fire exit which took me into the library which I also wasn’t expecting. And this security guard was seriously pissed off at me in a way that did seem to not really be about me. He was like YOU! IT’S YOU AGAIN! YOU’RE ALWAYS STAYING LATE! And I was like oh no, sorry, I just got here, and he was like NO I’VE SEEN YOU BEFORE. THERE’S PEOPLE SLEEPING IN HERE, THERE’S PEOPLE FUCKING IN HERE. SO NEXT TIME JUST STAY IN HERE. And I was like oh no, please can I leave now, and to be fair he did let me out of the library. But then things got conspiratorial and – if I’m right in remembering – we were accused of having sex in the studio! Which again, looking back on it, just so clearly seemed trans/homophobic, but at the time was just bizarre enough to kind of baffle me? And then Space Studios served us an eviction notice which they sustained even after they admitted that they (again, farcical) had got us confused with someone else who had actually been sleeping/fucking in the studios. (If that’s you – bravo, please contact us for research purposes: Between the Stacks 2, here we come.)

In the film segment of Between the Stacks I directed, you and Silver have been transformed into pups owned by Wet Mess’s evil Dickensian slumlord. The switch from live performance to film creates this extra transformation where we as the audience have a remove from you and Silver being in space, speaking to us, speaking to each other, feeling your bodily presence, to then seeing you through a projection, mute and pupp-ified by Izzi’s amazing costumes. And the way Alfie shot it, in quite a hectic choppy way – switching from bird’s eye CCTV-esque vision to up close slobber cam – puts us in a very different relation to your bodies. It’s much more voyeuristic.

It’s like we as trans people are ghosts haunting our own city. And those fault lines between who sees us, how and when, can be absurd and tragicomic as well as devastating. How does time operate in your work, and do you see your self in a cohort or legacy of trans filmmakers/writers playing with time and reality?

Thigh Rise takes place mostly over the course of one night, as does Poppets – flashback/time jump aside – and Hormonal. Principal Boy exists within this one theatre space, where time moves differently. Practically, time has passed between the audition which makes up the bulk of the film and the end performance – but we don’t have access to that time, we are stuck inside the theatre. I’m drawn to this one-crazy-night format because I like the idea of staying inside an escalation, creating a moment where reality breaks and a new logic has to be followed. This moment of transcendence from routine, a chance encounter, skiving off your job, following someone, doing something when you aren’t sure why.

I do feel like trans filmmakers – or maybe I should say, trans filmmakers whose work I vibe with – have such a different relation to time than cis filmmakers making work about trans people. We’re supposed to have surpassed some of the cliches but to me contemporary cis filmmakers are still so obsessed with the before/after, the reconciliation of the past and present in the most reductive way imaginable. This makes me think of the time jump in Between the Stacks, which takes us from this romantic montage of yours and Silver’s heyday in the studio to a time after the studio’s destruction when an Essex geez estate agent is showing posh girly Patricia around the space. And the transformation of you and Silver is of human to pup, rather than F to M, etc.

I find it very cheap and lazy in regards to the language of cinema to follow a one-gender-to-another-over-time narrative, it’s like the screenwriter handbook version of trans experience. My experience of reality has changed so much over the last 6 or 7 years in ways I couldn’t define in concrete terms, let alone fit into a neat little visual. There’s so many different points of transition, a million forks in the road. I think something like Stress Positions articulates this well. Director Theda Hammel draws a relation between gayguy Terry Goon and trans woman Karla; Karla describes her transition as a break from gayguy life; a choice she made to escape, or at least improve a shit situation. And I found the different ways she interacts with, is treated by and/or read by the various characters – her cis lesbian partner, gayguy bestie, chaser-y delivery guy and the as-yet undefined Bahlul – to be very well observed and compelling.

The time in which I would receive like 5 different types of treatment based on different perceptions of my gender which I also had to guess in one day is – for the moment – less present. Although I have a sense this could really change with the current political moment, changing access to healthcare and a heightening scrutiny. For now, a relatively passing white trans masc existence leads to some farcical experiences, which when I stop to think about it is a level of extra labour and bureaucracy that a cis man wouldn’t have to deal with. So it is quite strange to pass as something in certain contexts, and see the similarities between myself and cis men, but also feel that I really have no idea what it’s actually like day to day to live that way – without any of these administrative tasks, in a different economic reality that I probably don’t even realise is entirely linked to my transition.

It’s funny when you can see a grand narrative but not always clock it in your own life because it’s like, well, I’m a person with agency and I’m out here living my life, I’m not a statistic or a victim and I don’t see myself in this bogeyman in the media. But there’s a lot of people for whom the media landscape is the only way in which they’ve interacted with trans people, knowingly. And that can feel like a slightly ghostly existence. There was a time maybe 6 or 7 years ago where I thought if only there was a way to acknowledge other trans people in public in a way that felt safe and friendly. And then in London at least, there suddenly seemed to be so many trans people about that this concern felt quite silly in retrospect, perhaps was just a reaction to my own inexperience, and was also kind of inconceivable to certain younger/greener trans people I spoke to. Now, I’m starting to feel it again. But I don’t want to accept that reality.

It’s been a while since Thigh Rise and lots has changed. (We got kicked out!) (You’ve made another hit film!) Trans people have been fucked over more by this government. How do you view the piece now? And has its resonance changed for you?

I like Thigh Rise, I like its sets and costumes and vibe and it feels like a whole world unto itself. I feel proud that I made it happen without any backing and got it finished. I think everyone in it is great and it was shot beautifully by Rosie Taylor. I also love the soundtrack made by Cix and I think it achieves some of what I set out to do.

I think I learnt a lot about scriptwriting from Thigh Rise, in that I tried to be as economical as possible in getting across the main concept, the romance and the conflict. I’m not sure I totally achieved this because it’s so easy to be self indulgent when you’re literally doing a passion project. When you’re otherwise trying to be economical, these little indulgences – clinging on to a joke you like, lingering on visuals – really stand out. It’s also quite funny to be doing a pastiche of something that was never intended to be that good – like a B movie or an exploitation movie. I like the strange off-kilter quality that going against good taste achieves, but I also want to be able to deploy it a bit more mindfully in future projects, as I think we’ve probably reached a saturation of intentionally camp camp in culture. And like Forest says, fuck nostalgia.

What are you making now?

I’ve just written a book called Jaw Filler with Charlie Markbreiter, coming out with Montez Press this November. It’s a trans sci fi detective novel written from the perspective of multiple trans characters all enmeshed in this twisty heightened narrative.

I’m also working on a performance and will be making another film over the next year as part of a long term project with Studio Voltaire.

Writing the novel has been really instructive to these other elements of my practice. There’s things you can do in a novel that you really can’t do in performance or film, for one thing I joked a lot that I really went high production value in the novel. The limit was my imagination, rather than like ‘how do I shoot a car crash with no money?’, etc. It also taught me a balance between treating one’s characters and the worlds one creates seriously, while still having fun with tropes and archetypes. Because I often find trans character studies or slice of life films rather tedious, I tend to overcorrect and throw out the entire concept of character development.

Spending so much time inside the minds of the characters in Jaw Filler helped me reconsider that. I’m not sure where that leaves me in regards to the next film project, but I want to make something that engages with the medium in an intentional way, and I want to reflect on how I portray transness. In the novel, you’re inside these characters’ heads and there’s only limited descriptions of what they look like, which is also unreliable because it’s coming from themselves or the perspective of other characters. In film, to a certain extent what you see is what you get – even though film provides an opportunity to lay out its own rules of engagement.

For example, Divine in Female Trouble is a young girl and everyone treats her accordingly, so while there is humour and absurdity to her presence, as a viewer we can take her seriously in this role because the film is telling us how to see her. What I’m more used to seeing is: camera is pointed at a trans person, and you’re either supposed to be able to tell they are trans because the character is trans, or it isn’t spoken of at all and their presence is supposed to signal some kind of affirmative action. I thought a lot about trans representation and took it somewhat seriously as a labour issue in Principal Boy, and now I want to move on from that and create my own language of engagement rather than critiquing the existing ones, especially as they’ve been cut off at the knee before they even began. The DEI era, the visibility era, the aspirational assimilation era, the trans content boom, whatever you might call it, is over.

And do you have a studio! How do you find time to create in this city?

I’ve just moved out of my space at Studio Voltaire, which I had as part of a scheme for low income artists. I had it for two years and it was great, although towards the end I did feel a burden of responsibility to be making the most of the space. It was kind of double edged, I felt I should be excelling professionally – having studio visits, which I find confusing, with important people – and also living out this artistic fantasy of shutting myself in the studio and creating with freedom and abundance. Neither of these things really happened. I took a lot of naps.

It’s hard to find time to create: I’m realising more and more that I need time to be bored, to let my mind wander. And the stress of navigating part-time work, freelance work and creative work – some of it paid, some of it barely paid, some of it not at all – doesn’t leave much space for that. This intuitive mode of creation is also deeply incompatible with institutions and funding structures, which force you to have a very strange relationship to your own ideas. You’re basically making the work in your head, reaching its endpoint, just to write a funding application, and then maybe you won’t ever get to make that work. Or if you’re successful and you do, it’s honestly probably not going to be very good because the entire creative process has been truncated into this series of imaginary focus groups between you and the Arts Council Social Good & Efficiency Scale. Or by a random charitable/arts organisation who set themselves up as another toll on the road to the Arts Council money pot, with their own even more specific set of requirements. By the time you get funding, it honestly doesn’t really matter if the work is ‘good’, just that you make it and then fill in your evaluation form.

It can feel like it benefits you less to make work that has any level of complication – like it’s better to find a niche and stick to it. And in my silly world, that’s often related to identity: translating your identity in a fairly reductive way, which also invites Elite Capture. If I was a normal guy, maybe it would be choosing one really specific niche research interest and just keeping with that. Or pretending I was really good at working with an oppressed group of people. I feel quite queasy having to pretend my work provides some kind of social good for trans people, even if I think, in its own way, it does. On a material level, I try to hire trans people and collaborate with trans people, but I hate the way funding bodies and the professionalisation of art pushes you to make huge formal progressive claims for things you should just be doing because you think it’s right. It feels very cynical, under the cover of something earnest. Which I hate!

None of this would really bother me if I could live an OK life through entry-level part-time work and a few bits of art here and there. But it seems like even people who seem outwardly successful in the art world – the publicly funded side of the art world, as I don’t know much about the commercial world – are struggling monetarily, unless they have a well-paid day job, or – yes – inherited wealth and assets. And then this idea of the struggling artist can provide cover for people with a well-remunerated day job or inherited wealth to compete with people trying to make a living from these underfunded arts opportunities. It’s a very uneven playing field. One thing I found really helpful about the space at Studio Voltaire was having an environment to talk to people about these material concerns, about the practicalities of making a living as an artist. I hope I can find a space like that again; I learnt a lot.

*

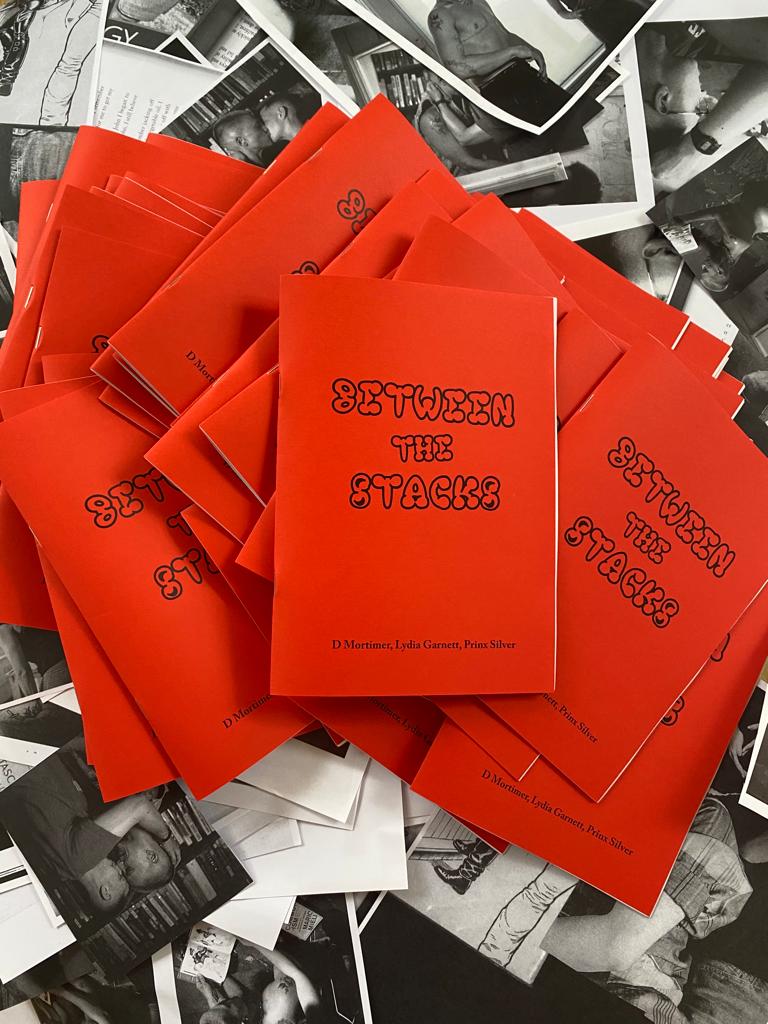

Visit Maz Murray / @maz_murray and D Mortimer / @fragile_masculinity to learn more about the artists’ work and to buy the Between the Stacks zine and T-shirts!