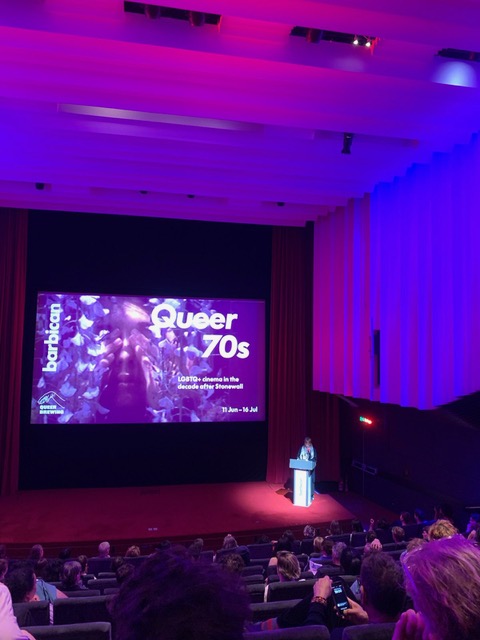

11 June 2025: Selina had been invited by Barbican curator Alex Davidson to select the opening night film for his Queer 70’s season, and now here we were in Barbican Screen 1. We chose to fill the venue’s main screen with a celebration of the legacy of Barbara Hammer, a true pioneer of LGBTQ+ cinema, with a special screening featuring her groundbreaking 8mm shorts Dyketactics, Superdyke, Women I Love and Double Strength, with an extended introduction by Selina.

With a career that spanned 50 years, Barbara (1939-2019) is recognised as a pioneer of feminist and queer cinema. A visual artist working primarily in film and video, Barbara created an unprecedented body of experimental work that illuminated lesbian histories, lives and representations, starting in the 1970s.

The films Barbara made during the 1970s reflect her newfound lesbian identity, sexuality and community. These frank, lustful shorts came out of the women’s movement, and particularly its California Bay Area crossover with hippy culture, which created an incredible era of personal and political liberation. Her filmmaking changed the landscape not only of cinema, but of queer lives and histories. The event celebrated her legacy by pairing her four key shorts from the 1970s with a newer tribute to Hammer by filmmaker Deborah Stratman, working with Hammer’s archival footage with the filmmaker’s permission, and with electric live poetry by Joelle Taylor and a memorable reading by artist/filmmaker Lisa Gornick, all playing to a full house of all ages, genders and sexualities.

Here is a transcript of Selina’s introduction:

Thank you, Alex, for this invitation to collaborate on this special Barbara Hammer event, which is opening the Barbican’s fabulous Queer 70s season. It’s a real honour to present Barbara’s films this evening, and it’s been a joy to work together! The first thing that I want to say, looking out onto this beautiful full cinema, is that Barbara would have absolutely loved this. She loved being the centre of attention. Born in Hollywood, it’s no mistake that her mother wanted her to be the next Shirley Temple!

Barbara was an American queer feminist filmmaker, visual artist and lesbian activist with a career that spanned over fifty years. She made over 90 films ranging from experimental shorts to long-form essay films and feature length documentaries, as well as performances, installations, photographs, collages, drawings. Born in 1939, Barbara did not begin making films until she was 30, which coincided with her newfound life as a lesbian. She claimed to never have been in the closet; in fact, she did not become a ‘lesbian’ until a year or so after making her first film, noting, ‘As soon as I heard about it, I did it’. Her groundbreaking experimental films of the 1970s reflected Barbara’s newfound lesbian identity, sexuality and community.

The films that we will be watching this evening, came out of and through the women’s liberation movement in California, an incredible moment of personal and political liberation for many women, including Barbara. Luckily for us, she documented her life and these times, leaving us a cultural record and memory of that moment. Many of the women in the films were Barbara’s friends, lovers, mentors and part of the lesbian community she was embedded in. The work captures the rush, joy and messiness of lesbian love and sex, women’s bodies, sexuality, lesbian eroticism, feminist politics and consciousness-raising, the power of women together – always with a desire to experiment formally. Barbara had a profound commitment to a cinematic embodiment, she wanted her audiences (and in the 70s it was predominantly lesbian, women-only audiences) to touch and feel the lesbian image-making they were seeing on the screen. This is what she called her lesbian aesthetic. As Barbara said:

My work makes these invisible bodies and histories visible. As a lesbian artist, I found little existing representation, so I put lesbian life on this blank screen, leaving a cultural record for future generations.

Barbara’s work has had a huge impact of generations of queer film scholars and filmmakers; her work remains of fundamental importance for a new generation of artists exploring new voices and new modes of experimenting with the moving image. In the 2000s media artists Liz Rosenfeld, Ingrid Ryberg and duo A. K. Burns and A. L. Steiner expressed their appreciation for Barbara’s body of work. This was an articulation by a generation informed by queer activists’ commitment to trans inclusion and sex positivism, that had previously been seen as in opposition to the context of 1970s cultural feminism in which Barbara’s films were made. In fact, the criticism that always hit Barbara the hardest was the dismissal of her 1970s work as ‘essentialist’: this was something that she found simplistic, and she continued to address these accusations throughout her career.

Barbara made a big impression on my career as a film programmer and queer activist as well. I first met her when I was programming at Flare (formerly the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival) in 2003. We had invited her film Resisting Paradise to the festival, a film about the intersection of art and life during World War II, and how to resist as an artist. To my delight, she came to London to present the film in person. I hosted the Q&A. It was then that I realised that a Barbara Hammer screening is a real happening. My carefully planned post-screening questions were quickly ambushed by Barbara, as our Q&A turned into a A&Q led by Barbara, engaging her audience and me in conversation! At one point, Barbara piercingly looked at me and said, ‘Selina: what are you doing to do to resist?’. It was at that moment, as I tentatively mouthed the words, ‘Show films’, that I realised that film programming could be both personal and political and in fact this is what I must do, show political films politically, show queer films queerly.

After this memorable public encounter, we stayed in touch on email. My partner’s sister was studying at NYU, and so I got to spend time more time with Barbara in New York during the 2000s. I visited her downtown studio, she gave me her hand-typed filmography and some press clippings about her work, she gave me some of her films to watch and showed me some which she was digitising in her studio. She was already thinking about her archive and legacy. We ate cheap lunches together, we talked about cinema, books, her recent cancer diagnosis, what was going on in London in the feminist, lesbian/queer film scene and the experimental film scene: two circles and communities she inhabited. She was so warm, direct and friendly; she was incredibly flirtatious and gently challenging too. I remember blushing a lot, happy to sit in her orbit. Over the years, I programmed her films, wrote about them, interviewed her, advocated for her as much as I could. I was happy to have helped in some way to be a stepping stone for her 2012 Tate Modern major survey, ‘Barbara Hammer: The Fearless Frames’, curated by Stuart Comer. When she was coming to the end of her life, I wrote her an email to thank her for her inspiration, her films, her life force. I didn’t hear back but I imagine she would have read it.

Last Friday, in a lucky moment of online and IRL cine-synchronicity, Le Cinema Club, the online streaming platform put up Barbara’s film Audience (1993), her brilliant, funny, thought provoking and flirtatious film about her encounter with her public. Here we see the work that Barbara put in to create lesbian audiences for her films.

For many years, Barbara was almost alone as an openly lesbian filmmaker. Virtually excluded from the boys’ club of the film avant-garde, she showed her work in women’s bookstores, coffee houses, and women’s studies classrooms, often organising the events and carting the equipment too. Determined to promote women’s media, she organised weekend workshops and classes to teach women filmmaking skills and set up screenings of women’s avant-gardists of the past, including her touchpoint, Maya Deren.

In Audience, we watch Barbara film her audiences before and after screenings of her 1970s works in London, Montreal, San Francisco and Toronto. As a film programmer, this has always been one of my favourite films of hers, because it offers a rare insight into the newly-constituted audiences for lesbian experimental cinema, and the diversity of opinions and experiences expressed. One memorable section is when Barbara comes to London to screen her films at the London Film-makers Co-op. Women are sat on the floor and in a round semi-circle of chairs – cue baggy jumpers, big hair, smoking. One woman contrasts the joys and energy of the San Francisco lesbian scene with the realities of feminist organising in London. ‘Many lesbians are poor’, she says, ‘they’re depressed, the weather is not that great’. ‘Chips are awful’, another person interjects, ‘chips are awful… right’, the woman continues, ‘it’s very easy to get very heavily involved with hard work’. I wanted to quote this bit from the film because it shows how radical Barbara’s films of the 1970s were.

‘Amid fraught debates about representation of sex and sexuality’, Laura Guy writes, ‘a culture of suppression engendered by state enforced censorship, Barbara embraced pleasure as a vital part of lesbian feminist politics and experimental filmmaking.’ This was the shock of the new.

This evening will run a little differently: we will be showing a couple of films at a time, then break intermittently for readings by Lisa Gornick and Joelle Taylor, who I will properly introduce later.

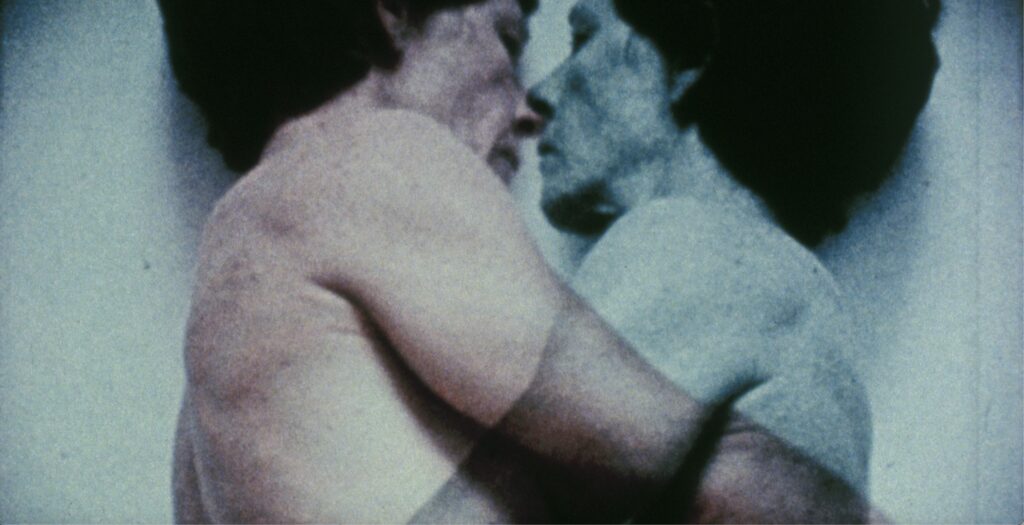

But first, we will begin in 1974 with Dyketactics, Barbara’s now-classic love-making film, a tabula rasa moment for lesbian experimental cinema. With its 110 lesbian images in four minutes, Barbara has called this look at female sensuality and sexuality, ‘an erotic lesbian commercial… a coming out film, celebrating what it was like to make love to a woman’. The camera is a living, moving presence capturing and framing and reframing caress and touch. After which we will watch Superdyke from 1975, likened by Barbara to a Bugs Bunny cartoon. We follow a group of shield-bearing Amazons (prototypes of the 1990s Lesbian Avengers) around San Francisco and then to a romp into the countryside. Her frenetic handheld style gives the film its humour, pace and energy. As with all her films of this era, it provides an amazing document of and insight into the lesbian subculture of the 1970s.

*

Welcome Lisa Gornick to the stage to read Barbara’s words from her memoir Hammer! Making Movies about of Sex and Life, published by the Feminist Press at CUNY from 2010.

Lisa Gornick is a filmmaker, artist and performer. She often combines all three in her films and live performances. She has made three award winning essayistic-comedy features: Do I Love You? (2003), Tick Tock Lullaby (2007), and The Book of Gabrielle (2016). Her short films include ‘Dip’ (2010) and ‘My Primary Lover Never Hollywood Kissed Me’ (1998). Since 2016 she returned to live performance using real-time projected drawing, music, speech and song.

We will now watch Women I Love from 1979. Working from Barbara’s comments that ‘the camera is a personal extension of my body, my personality’, this erotic yet playful film features Barbara’s four lovers captured over a five-year period. Love-making appears not isolated, but as part of a continuum of nature and intimacy.

*

Welcome Joelle Taylor who will read some extracts form C+NTO & Othered Poems.

Joelle Taylor is the author of five collections of poetry and one novel. Her most recent collection C+NTO & Othered Poems won the 2021 T. S. Eliot Prize, and the 2022 Polari Book Prize for LGBT authors. C+NTO is currently being adapted both for theatre, and into a television screenplay, and was featured on the Radio 3 documentary Butch. Joelle was recently honoured with a DIVA Award for Outstanding Contribution and was named in the 2025 Pride Power list.

Our final films in the programme are a shift in tone, more melancholic, self-reflective, and open-ended. First, we will watch Barbara’s film Double Strength from 1978. Another one of my favourite films, this is a poetic, touching and passionate study of the rhythms of a lesbian relationship. Barbara was in a relationship at the time with the choreographer and performing artist Terry Sendgraff. We see and feel again, the ways in which Barbara creates new cinema forms to express this experience visually, emotionally and intellectually.

Our closing film is by artist and filmmaker Deborah Stratman, Vever (for Barbara) from 2019. The film grew out of abandoned film projects by Maya Deren and Barbara Hammer. Stratman shot it at the furthest point of a motorcycle trip that Barbara took to Guatemala in 1975 and laced through with Maya Deren’s reflections on failure and encounter in 1950s Haiti. When Barbara knew she was dying, she worked with the Wexner Centre for the Arts, in Ohio and asked three artist-filmmakers to collaborate with her on three of her unfinished films. Barbara asked Deborah to work on her abandoned Guatemala film project.

*

Club Des Femmes were honoured to be invited to bring our Barbara Hammer programme to Outburst Queer Arts Festival 2025 in Belfast. We selected two of Barbara’s 1970s films – Dyketactics and Double Strength – and paired them with two of our favourite contemporary films about queer collectivity and sexual liberation: Liz Rosenfeld‘s Untitled (Dyketactics Revisited) (2005) and Alli Logout‘s Lucid Noon, Sunset Blush (2015) to celebrate what we called “50 years of lesbionic cinema.” Not only did we have another full house on the night (including a queer basketball team!) for the films and for Selina’s introduction, but Liz Rosenfeld joined us in person to speak about their film, and about their own artistic and personal relationship with Barbara.

*

And there’s more Barbara to come! We’re breathlessly awaiting Brydie O’Connor‘s feature documentary Barbara Forever (2026), which premieres at Sundance next week (24 January) and will have its international premiere at the Berlinale in February. News on UK screenings, coming soon…