By Helen Charman

Fetch the Bolt Cutters is available to stream on Spotify and can be pre-ordered on CD and double LP from Rough Trade.

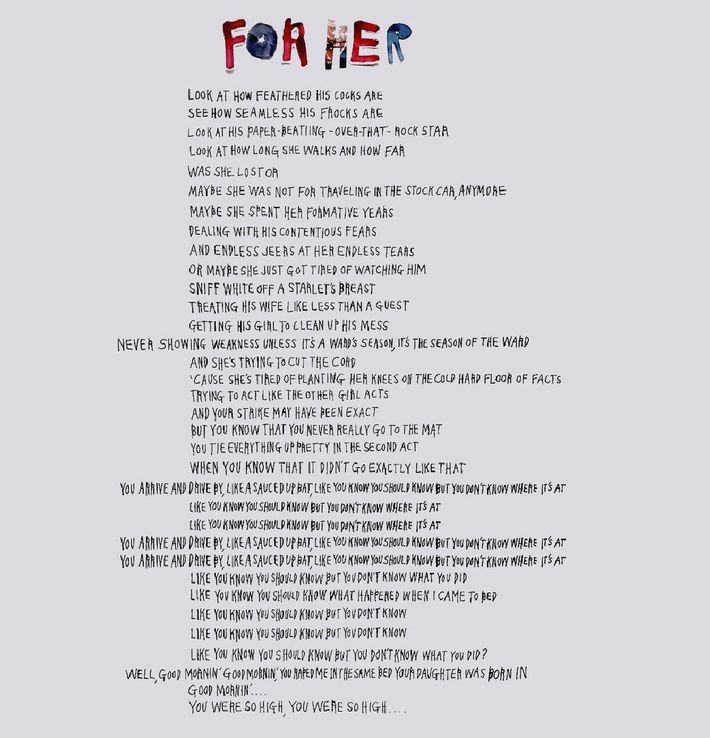

A friend — the friend who first introduced me, nearly a decade ago, to Fiona Apple’s work — described the experience of listening to Fetch the Bolt Cutters as ‘like being on fire, but wearing a fireproof suit’. There are different moments of ignition for every listener; for me, it comes most vividly in ‘For Her’, as Apple’s speaker returns to the site of trauma with a powerfully discombobulating sample from Singin’ in the Rain: ‘Good morning / good morning / you raped me in the same bed / your daughter was born in’.

As its title suggests, the song is a kind of collective offering, a representation of sexual violence as a shared burden: in an interview with Vulture, Apple stated that the song contains the amalgamated stories of multiple women. In that same interview, she continues:

Even though it’s an awkward thing to say in a song — “You raped me” — some people need to say it out loud in order to understand that’s what happened to them. And my hope is that maybe some women and men will be able to sing along with that line and allow it to tell the truth for them. Because sometimes it’s just really hard to say, especially if you don’t want to hurt the person who did it to you. It’s hard to say something that harsh about it.

In this way, the mantra-like repeating lines of ‘For Her’ — ‘Like you know you should know, but you don’t know / Like you know you should know, but you don’t know what you did’ — mimic, almost, the pathways of neural recall accessed by psychoanalysis: the resurfacing of repressed experiences, although here the repression belongs to the aggressor. It would be too simplistic — it would do Apple a disservice — to settle for an interpretation of this communality as a straightforwardly positive move towards resolution: ‘It started out me wanting to write something about my own feelings,’ she told Vulture, ‘but it was just too hard. I wanted to make it about not just me but about other people […] I needed to have a bunch of other women singing with me on it’.

Self-assertion can take too much of a toll, particularly when ‘justice’ — unreliable at the best of times — is not necessarily the outcome you are seeking: ‘if you don’t want to hurt the person who did it to you’. In ‘Relay’, the song almost splits itself into a round, as multiple versions of Apple’s voice alternate between a list of resentments ‘I resent you for being raised right / I resent you for being tall / I resent you for never getting any opposition at all’—and the frantic repeated assertion that violence begets violence, that retribution is never as cleansing as you think: ‘Evil is a relay sport / When the one who’s burned / Turns to pass the torch / Evil is a relay sport…’

Part of the mythology that surrounds this album is the fact Apple, who is now famously ‘reclusive’ in her retreat from public life, recorded it all in her own house: in an NPR interview, Apple referred to the house as ‘the womb of where I’ve developed into an adult’. It’s striking she uses the language of maternal enclosure: the womb/house is a place that forecloses any question of isolation or, indeed, of individuality. On ‘Newspaper’, her sister Maude provides the backing vocals whilst breastfeeding. This song sees Apple’s speaker addresses a woman who has been treated badly by their shared former partner, articulating feelings of simultaneous distance and proximity, of intimacy born from a shared experience of violence: ‘When I learned what he did, I felt close to you / In my own way, I fell in love with you / But he’s made me a ghost to you’.

The wounded, staccato chorus illustrates the futility of these attempts to connect, as Apple howls prophecies that won’t be heeded from her solitary vantage point:

And you’re wearing time, like a flowery crown

Sitting that, sitting that big cat down

And I’m alone on the summit now

Trying not to let my light go out

Aloneness does a lot of work in Fetch the Bolt Cutters, an album that, itself the long-awaited product of Fiona Apple’s isolation, was released in the midst of the mass social dislocation of the Covid-19 pandemic. How can we talk to each other about difficult things? How can we talk to each other at all? The thwarted impulse to connect — present, too, in ‘Ladies’, as Apple mourns ‘yet another woman to whom I won’t get through’ — structures the entire album: heralded by many critics as a piece of work rooted in generative collective rage, to me it sounds more like a documentation of the difficulty of finding lasting ways of transforming harm into communality, of striking the balance between self-accusation, closure, and solidarity.

Perhaps it’s only in such a space of entanglement as the ‘womb’ of her house that Apple could document her attempts to connect with other people through and despite distance, resentment, and violence, without seeing their rejection as a value statement; document the importance of trying to bridge a gap you suspect to be unbridgeable, and the moments of shared purpose that can bolster solitude: ‘And I know none of this will matter in the long run / But I know a sound is still a sound around no one’.

There is an almost-maternal protective impulse present, too, in Apple’s focus on articulation: ‘I’d like to buy you a pair of pillow-soled hiking boots / To help you with your climb / Or rather, to help the bodies that you step over along your route / So they won’t hurt like mine’, she sings in ‘Under the Table’. Unable to fulfil this preventative objective, the motif of vocalisation throughout the album — ‘Kick me under the table all you want / I won’t shut up’ — and its title, which itself references a scene in The Fall where Gillian Anderson literally breaks down the door of a sealed room where a young woman was tortured, offer instead a kind of furious relief; familiar, perhaps, for those listeners who have their own experiences of the long and weary struggle to find a name for what has happened to them.