In advance of a one-off International Women’s Day screening of My Name is Andrea by Pratibha Parmar, Club Des Femmes are honoured to publish this transcript from a career-spanning interview by Shamira Meghani, which took place on 25 November 2021 at the University of Cambridge Faculty of English Postcolonial and Related Literatures & Queer Cultures Graduate Seminar, chaired by Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell.

My Name is Andrea, directed by Pratibha Parmar

Rio Cinema, London, Sunday 9 March, 2 pm. Book now.

The Rio Feminist Flm Programming Group is delighted to present a recent documentary from one of the UK’s most respected queer filmmakers, Pratibha Parmar. Pratibha will be in conversation with writer, curator and academic Lucy Reynolds following the screening.

*

Visual Justice: Pratibha Parmar in conversation with Shamira Meghani

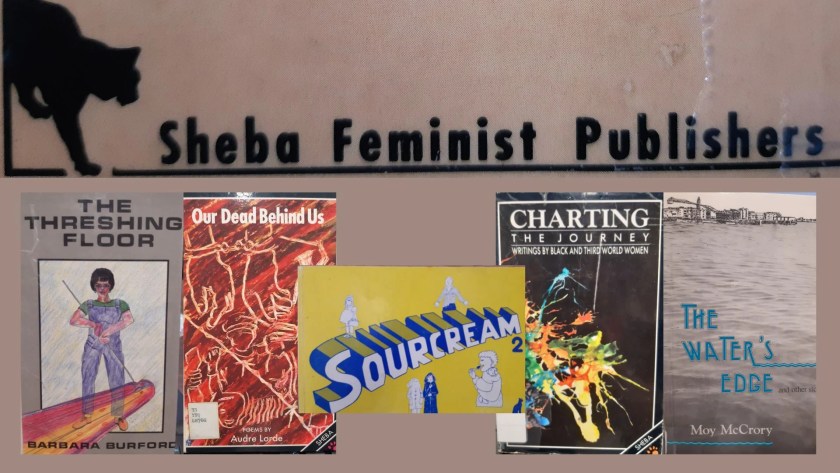

Shamira Meghani: There are so many places that we could begin, and I have wondered whether to ask you about your recent work and then look backwards. But re-reading some of the interviews you’ve done, and essays you’ve written, I’ve realised that there’s a really important reason that in A Place of Rage, your 1991 documentary, June Jordan begins by articulating the constrained context in which her political life began, including not being able to travel outside of New York because she could not assume that she as a Black person would be able to use the bathroom or get a glass of water. Jordan is emphatic that change happened in her lifetime, and that they in the civil rights movement collectively had to make change. Relatedly, perhaps one of the most revealing interviews for me to read was the one you did with others (Menika, Alice, Sue, and Ravinder) on Sheba Press and its evolution in 1986, because at that point, change is clearly in motion as a result of activism. Yet, even at that point, you’re talking about a past from which feminist organising has moved on, but also that people are beginning to take for granted the results of that organising while not yet making the kinds of changes that Sheba Press became known for. And, interestingly at that point, Sheba was spoken of as the kind of ‘conscience’ of the feminist publishing industry: the press which addresses anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-homophobic, disabilities-conscious writing and ideas. So in both those contexts you get the sense that a lot has changed, and yet that more necessary change has kind of stalled.

A Place of Rage is available to rent on Vimeo via Kali Films.

I’d like to put my question into a broader context: it is hard for those of us who were even around at the time to really remember the sort of quotidian texture of life without mobile phones and Internet, and it may be harder for those born after the mid-nineties to imagine a sort of fast-changing, fast politically changing, world prior to mobile telecoms and Internet connectivity, especially given its embeddedness in our first-world context (obviously that’s not the case everywhere). So that point isn’t an accusation about a failure of imagination for those who come after the advent of the Internet, but rather what I wanted to pinpoint was the way that different kinds of material infrastructure impact ordinary, day-to-day activities, and consequently organising. So to return to the subject of your work, and to your own organising work, you and your feminist anti-racist comrades organised using what seem very centrally collectivised tools and strategies, with this kind of outward ripple effect. Now I wonder if you can talk to us a little bit about that time, about how you made collective change, and what you think the context of the time enabled or prevented. And I was thinking, in relation to that, given the change in infrastructure, are there strategies and approaches lost to the present, even as we can celebrate the broad benefits of digital infrastructure to feminist anti-racist organising?

Pratibha Parmar: It’s fantastic to be reminded of the optimism and the level of hope that we had as communities of resistance at that time. Thinking about my own roots of community activism, the groundwork for that was laid by the fact that I am the daughter of working-class immigrants to the UK. We came at a time in the sixties when Enoch Powell had made a speech about Rivers of Blood, and I was called a Paki within the first few days of being in the school playground. I was naïve as a twelve-year-old, I didn’t understand what that meant, so I retorted back saying, ‘Well, no, I’m Indian, I’m not Pakistani, I’m Indian!’ I think I just had to find a really quick way of understanding and protecting myself, and that’s partly where my desire emerged to find a language, to find communities, that could help me understand what my positionality was at that time as an outsider.

Over the years, my community activism was nourished by exposure to African American women writers and activists. Reading Angela Davis was very much part of my growing consciousness around class and race. You know, my mother worked in a sweatshop and earned ten cents sewing a pillowcase, before she was made redundant. Later she had an industrial sewing machine at home, and there was immense pressure on her as ‘the man’ was coming to pick up the clothes the next day. She’d be up until midnight, and we would be up with her, cutting as the garments came off, folding and putting them away. So I had that visceral experience of class exploitation, and how it’s gendered and racialized. When I went to the University of Birmingham as a postgrad student, just as Stuart Hall was leaving, I was trying to find the language and theories to articulate that. My thesis at the time was on South Asian women and race, class and gender, and how that played out on the factory floor. And of course then the Grunwick strikes happened, and all that was very much part of my politicisation and community organising. I was discovering feminism, which got more and more delineated when trying to understand the nuances and complexities of what it meant to be a feminist to me. At the same time I wanted to understand my burgeoning queer identity, and looking for community to be in solidarity with, for emotional structures of support.

With Sheba Press, what did I know about publishing, what did any one of us really know about publishing? Obviously we knew editorially what kind of books we wanted to publish, what kind of stories, which writers we wanted to encourage, what we saw missing in the feminist publishing world: the glaring absence of women of colour’s voices and writings. But then to actually learn how to prepare the manuscript for pagination, what were font sizes, how to create publicity materials, that was another thing altogether. Going back to my undergrad days in Bradford, there was a community silkscreen workshop where I remember designing these posters for anti-racist meetings we were going to be holding, or for the march we were doing against the fascists. With a few other people, I was literally going on the printing press and silkscreen printing hundreds of posters, going out at night with buckets of glue and a big broom, and sticking these posters up all over the city, anywhere we could find a space on the wall. But you just did that, you know, you find the means through which you can communicate.

I think digitisation and access to the Internet have actually expanded the reach of ideas and activism. I’m thinking about the climate change activism of so many young people, particularly the indigenous young women who are at the forefront of the climate change movement, and that incredible turnout in Glasgow recently. That might not have happened on that scale, and with those kind of international alliances, were it not for the Internet. Of course, we could always talk about what kind of surveillance we leave ourselves open to. But at the same time, three white supremacist men just got sentenced for Ahmaud Arbery’s murder when somebody came up and showed the video that they had taken on their phone of what happened. So there are ways in which new technologies can work in our favour for justice.

SM: I like that. It feels like it’s got some of the optimism that you were talking about, and we could all use a lot more of that.

PP: Absolutely. I mean we’re seeing this move globally towards fascism and to the right, and it’s against the tyranny of despair that activism has to be our solace and our salvation, and our way forward in imagining and continuing to imagine different kinds of futures.

SM: Thank you. That’s so enlivening, I love it. Okay, I’m going to ask you about the aesthetics in your early work. We can think about the role of women in contexts of care – especially care for others – as being naturalised, and I think a lot of your work has been about denaturalising that care, but without diminishing the necessity and value of care. The place of care seems to me to have always been circumscribed by immediate concerns of care within the western family unit, whereas your approaches to care seem to extend far beyond that, in that there is a resonance through your visual politics more broadly. For example in Sari Red, a short poetic video work from 1988 which commemorates the racist killing of Kalbinder Kaur Hayre in 1985, your attention to cultural specificity takes care to juxtapose images of blood splashed with a red sari and its intricate careful embroidery work, likely to have been made by the hands of women. By contrast, in A Place of Rageyou intersperse images of Angela Davis at work more formally, with her running, working out at the gym and playing squash, and essentially practicing self-care. But I want to say that more generally, there is often an aesthetic tenderness afforded to your subjects that characterises your work. I wondered if you could say a little bit more about this, about the way your aesthetic approaches and choices are informed by a politics of care, and how you understand that and what you do with that.

Sari Red is available to rent on Vimeo, via Kali Films.

PP: I love that phrase ‘aesthetics of tenderness’. In the early years I wished I had gone to film school. I got as far as an interview at the National Film School in England, but I ended up having a very heated discussion about ethnographic filmmaking. I came in and said: no, we have to question these visual representations of what you see as the other. So I never got into film school, I learned by just doing it. Sari Red was made with a Hi8 video camera. A politics of care or aesthetics of tenderness might have come through the fact that I had the camera and I decided what affected me, what was painful to my heart, in what I was seeing around me. Kalbinder’s murder was something that I’d read about, that I knew about, and that had affected me deeply, because I thought it could easily have been me, it could have been any one of my friends. When anyone shouted racist terms at us on the street, our instinct was to shout back, and Kalbinder shouted back and got killed for it. I embodied her murder and her absence, and I thought: her life cannot just be another number in the index of racist murders. I wanted to do some kind of memorial to her, and the work comes from my need as a South Asian queer woman at that time to document that, as much for our communities as for myself.

My choice of subject matter, and then how I approach it, comes always from being on the inside of it, rather than being an objective outsider looking in. I’ve never been that kind of filmmaker, who’s supposedly objective. I cared about Kalbinder, who I didn’t know, but I cared about her. So I just wrote this poem, and then I put images together. That was one of the first videos I made. Suddenly it was in film festivals, and it was bought by MoMA, Museum of Modern Art in New York, and I was being hailed as this video artist, and I had to look up: what is a video artist? I had no idea! Anything I have done comes from a sense of outrage at injustice, and a need to challenge that injustice in whatever way I can, from being an activist on the ground to doing feminist publishing. I eventually landed in the space of the moving image, which for me is a natural arc. I think about my films as spaces in which I have attempted to do the work of visual justice, where the lens is one of a queer feminist of colour.

SM: I think you really have. It sounds very much as though the point is that you are within texts, your camera, your lens, your way of looking. That kind of aesthetics is actually drawn from your person, your being part of the communities that you’re making documentaries and films about. I’m going to ask you one more aesthetic question, because I’m interested in this crossover of politics and aesthetics. I want to ask you about beauty, actually, because in A Place of Rage you’ve got these very strident voices: Davis narrating her story of arrest and liberation at the hands of people’s dissent, and Jordan powerfully delivering her searing poetry. It’s really important that we hear those, but you’ve also interspersed down-to-earth images of both going about their lives: Davis with her dogs and Jordan making her way onto public transport. These sections also include the faces of young black women, one after another, smiling, connecting with the camera, and somehow owning the light across their faces, which I think partly comes from the way that you’re looking. Can you say a bit more about these aesthetic choices of yours for the documentary? What for you is the importance of beauty, perhaps even joy, in the context of the hard politics of race, gender, and the body that your primary subjects are speaking on?

PP: Let me answer your previous question about self-care. So one of the things I learned from being around Angela Davis, June Jordan and Alice Walker during the making of the film, and just before that as I entered into their lives, was how self-care for them was generative, it was a mode of survival, it was what fed their inner resilience. I learned about the relationship between them as political beings, public figures and their commitment to their bodies, to self-care, which was not in any sense a narcissistic commitment, but one that allowed them to continue the work they did and do in the world. It was really important for me to show that nuance and complexity in representations of who they were.

In terms of the beauty and the joy, here in the US the fashion for documentary films is to find a character and follow them over the years, and create a narrative around them. My own kind of filmmaking – which I’ve sometimes called a diasporic style because I’ve imbibed so many different aesthetic influences that have then fed into my lens as a filmmaker – addressed the negativity around how women of colour were represented at that time, though I think things have since shifted and changed. It was crucial to me to capture beauty, not in a physical sense but in terms of the hopes and dreams that all these young women had. A lot of those young women in A Place of Rage were students of June Jordan or Angela Davis. I watched how they were watching them in class when Angela was giving a lecture or when June was giving a lecture, and I saw the hope and beauty that created in them, the inner beauty that shone out in the way they related and looked up to Angela, or looked up to June. I just thought it was so beautiful -I wanted to capture that. And you know joy is essential, as we were saying at the beginning: without joy struggle is not possible.

SM: We’ve talked about what you’ve been doing before, but I want to give you a chance to say what you’ve been working on most recently. Which discourses and debates are you reframing in your new work?

PP: I have been working on a film called My Name is Andrea which is a hybrid documentary, a kind of drama and documentary, based on and using the writings of Andrea Dworkin. She was a white Jewish feminist, who was one of the most controversial feminist figures, I think, of the seventies and the eighties. The film isn’t about her, but uses her life and writings as a vehicle to address issues around femicide and violence against women and girls globally, because that was the theme of her life and the majority of her writings. I am also changing my discursive approach. I have always centred in the frame experiences of LGBTQ people of colour, but for the very first time I’m centring a white woman and a white feminist within the frame. And it’s been a really fascinating exploration, not least because everything we think we know about Andrea Dworkin we don’t, we really don’t.

Towards the beginning of my film there’s a clip from when she was invited to Cambridge University to a debate on political correctness. She gives this ten-minute speech which begins by quoting James Baldwin and completely dissecting how whiteness was created in America through the genocide of the native people and through slavery. It was a revelation to me that this white feminist – who I had thought was very essentialist, very singular in terms of how she saw women’s struggles – was talking about the creation of whiteness. I think it’s also interesting to look at her now when radical feminists are quoting Andrea Dworkin in support of transphobic arguments, but when I spoke to Roz Kaveney, trans writer in the UK, she pointed out a paragraph in Dworkin’s first book about a spectrum of sexualities, a spectrum of genders, how nothing is fixed in any way. She talked about transsexuals and transsexual rights, because at that time the language was different. And then I found this radio interview where she’s talking about how she is compelled by the ideal of a genderless society and how she finds the words ‘male’ and ‘female’ quite toxic and reductive. And I was like: people who have been claiming they know Dworkin don’t know her really.

There’s this demonization of a feminist who was problematic – my film isn’t a hagiography or anything – but she had some really interesting things to say about violence against women, about structures of patriarchy, which went across so many different layers of meaning. I also think this is a very interesting historical moment to revisit 1970s and 80s feminists, some of whom have been reduced to a stereotype of what they had to say, when in fact there was so much that we could learn from them, and we have learnt from them, that we have inherited from them, but we don’t even know it.

SM: It sounds like your bringing your lens to Andrea is going to give her back to us as a comrade, of a kind that people have forgotten in lots of ways, which is great. Thank you for such a rich and enlightening discussion, it’s been a real privilege to talk to you.

PP: Well thank you so much, I really enjoyed all your questions.

This is an edited transcript of a discussion between Pratibha Parmar and Shamira Meghani held at the University of Cambridge Faculty of English Postcolonial and Related Literatures & Queer Cultures Graduate Seminar on 25 November 2021. The event was chaired by Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell and introduced by Alina Khakoo. The transcript of the contextual introduction is available here [PDF].