By Martina Attille

Artist Leena Habiballa, is a research-based practitioner who has emerged into the poetics of moving image production and research on knowledge canonisation, language, and care out of an academic grounding in cellular and molecular biology, the science of genetics, genomic medicine, and a PhD in the Biology of Ageing.

Habiballa is one of several artist members of not/nowhere, the artists’ co-operative situated in east London, an area well known for its history of shifting demographics and the complex legacies of homemaking, emigrant and immigrant people who contribute to our economy and culture in the capital city.

Habiballa is an artist working in an artistic context occupied with how the aesthetics of art and voiced critical materialism can create transformative environments for communication, learning, knowledge, and care. This scholarly context actively invites a considered curation of cultural critique and the promotion of moving image production tropes that give individuals, communities, and arts organisations access to emerging ways of thinking about and receiving new knowledge about art methodologies and functions. While suspended reverie (2024), a work of direct animation still in progress, describes the imagination of an artist who is calculating her next formal move through a deep regard for an ethics of reconciliation, Habiballa’s debut moving image work Dead As A Dodo (2022) gives insight into the terra firma from which she breaks interdisciplinary new ground as artist and scientist ‘trying to re-examine my field, its legacy and history’.

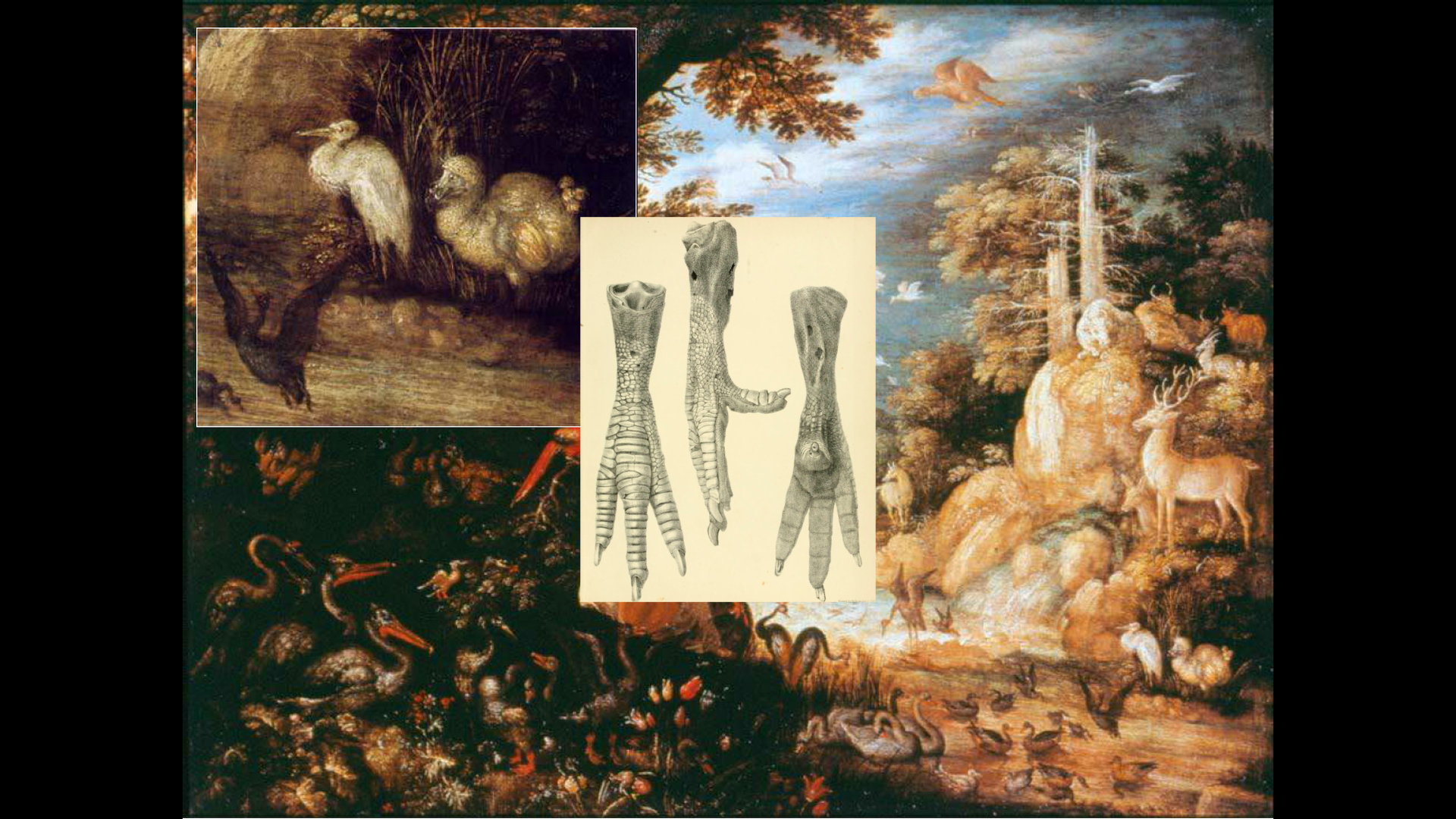

In three remote, exploratory recorded conversations, artist Habiballa gives insight into collaborative practice, freedom of expression, and the agency of language to reimagine dominant narratives. The conversation extract presented here indicates how Dead As A Dodo was inspired by reading a book of poetry by Zaina Alsous during the COVID-19 pandemic, during a lockdown phase. The performativity of Zaina Alsous’ poetic style raised questions for the artist about why the dodo had to die and the agility of the written word. Consequently, expansive reading and picture research engendered a concern for solidarity with the environment and to see things from the dodo’s perspective having lived on the island for many years without any problems, rather than that of the colonial imagination in which the bird ‘had to go’ resulting in their extermination by settlers in a settler colony. Habiballa presents Dead As A Dodo to think about the natural world as something deserving of mourning.

In conversation with the artist, framing the use of artistic methodology is key to entering the promise and delivery of Habiballa’s contribution to arts in the UK. Here is a season worthy of note. Transnational utterances and exchange are relevant to a time, such as this, of the political remapping of geopolitical borders and the interdependence of our systems of trade and commerce, which includes art and science as much as it does the trade of food, fuel, minerals, and other commodities. Habiballa’s moving image work is contemplating deep ethics, a deep longing to fathom and respond to nomenclature and appellation, the powers of language to bring into being, position and control ideas and things including objects and subjects that emanate from language as performance and action. In other words, the artist has stepped into a Derridean paradigm in which she answers an aporic call that awaits an arrivant (Derrida 1993: 65), with her response, here I am, artist. Here I am, open to an existentialist awakening in the midst of hierarchies of death and dying, open to the limits of truth or death where we wait for ourselves and each other.

Martina Attille: Your film was quite moving, because the Dodo story is pretty much unknown, isn’t it? What’s most depressing is a sort of misinformation, that this bird could have been mourned in a different way, that there was actually human agency in these animals disappearing. If we knew that, it may have kept us vigilant.

Leena Habiballa: Thank you. I also didn’t know that story about the Dodo until I read it in Zaina Alsous’ poetry collection. I grew up with a particular story in school, that these birds, native to Mauritius, didn’t have the instinct to fight back because there were no predators on the island. The accounts we were given painted them as stupid, bumbling creatures – big and ugly and clumsy – that couldn’t fly despite having wings. That was justification for their extermination. Its extinction wasn’t framed through the genocidal acts of Dutch settlers who had transformed Mauritius into a penal colony and exterminated this bird for sport. In effect, I was socialised into accepting a colonial logic, and seeing colonial death as natural and normal.

I made this film in response to a filmmaking prompt on race and identity. I wanted to decenter the human in the retelling of colonial history and think about race as a colonial category, the process of colonial naming, of creating a hierarchy of life in order to extract from and dominate it. I thought the Dodo was the perfect example of that kind of race-making in nature. The natural world is just as much a colonial subject as we are (though this distinction is itself colonial), and often is the training ground for some of the worst technologies of colonial violence, before it reaches us. I wanted to think of the natural world as something that is deserving of mourning as well, not just because of parallels between the Dodo and the racialised human as colonial subjects, but in its own right.

MA: I appreciate that term race-making, as something that’s actually produced, and requires people to be accountable for its production. This continuously falls on the racialised subjects rather than on the “race-makers”.

The poet’s line in Dead As A Dodo about “entering the empty cage, hips first,” evokes the sense of using the Dodo as a way to dismantle the colonial imagination but also as a way to filter through the liberalism of speaking about racialised institutions and racialised language. This metaphor of the empty cage is one, I think, in which you enter, as a scientist and a person who is interested in social justice and the moving image. So my question is, do you enter the empty cage as a scientist emerging into an artist?

LH:

I think I enter it as both. I think I enter as an artist trying to re-examine my scientific field and its legacy and history. I think it’s an attempt to use a different mode of being, an artistic mode that allows me to renew my approach to my field in a more imaginative, embodied, and sensory way.

As a scientist, I was really interested in what the scientific justification for the eradication of the Dodo was by British, Irish and French naturalists working in the 19th century. They painted Dutch settlers as seekers of knowledge, these men who made great sacrifices to further our understanding of the natural world, effectively spinning genocide as a noble, intellectual exercise. Science makes meaning of death through social process but sees itself as immune from political and social forces. It imagines that it exists outside of these realms and – at least in the way I have practiced science – it alone cannot hold their interrelations and co-constitutive nature. In that sense, it rarely interrogates the categories it creates of the natural world.

Political and social theory gave me the language to understand the different hierarchies of life that continue to be concealed in scientific language, the colonial legacies that are obscured by scientific practice. But, I wanted to transmit this information and insights in a way that was imaginative. There is already embedded within science this idea of narrative and storytelling to make data legible and interesting to people, so I thought why not pursue this outside of its utility within my scientific practice.

MA: You’ve got the sound of the Dodo that becomes intense towards the end. What, in fact, is that sound? There are no recordings of the Dodo, are there?

LH: In my research on the Dodo, I came across groups of scientists who looked at its anatomy and tried to recreate its sound based on their reconstruction of the vocal cords. I found this really disturbing. It felt like it was part of the same colonial apparatus, owning the whole life of this Dodo – deciding when it should die, deciding when it should come back, how we re-encounter the Dodo through sound. I found this really violent. So, I wanted to completely distort that process and invert its logic by revealing its grotesqueness.

By playing with the sound and creating these really harsh pitched and deep distortions that challenged the idea of a perfect scientific reconstruction of an extinct animals’ sound without a reckoning with its colonial history.

Another project I came across in my research was attempting to revive the Dodo in this Jurassic Park way. And it’s so interesting because I think it completely misses the point — you can’t restore this animal as an individual creature without restoring its community and environment, which has also been obliterated. Not letting it rest and bringing it back to assuage our own guilt about exterminating it is its own kind of violence. Do we open this door to reviving extinct creatures, or do we leave it and try and learn something from its history? I do think that science is limited by its own troublesome relationship to history.

MA: Speaking personally as somebody who is engaged with your work and our conversation, I really value your professionalism within the scientific world. And I value your critical perspective, to inform not only your artwork but also to inform the scientific community so it can open up conversations for people who want to come into the scientific field and maybe anticipate some of the challenges that they’re going to encounter.

I was quite curious about what you picked up from the poet mining English for her own purposes and having access to another language and how you identified with that as a bilingual or multilingual person.

LH: Zaina’s book helped me articulate for myself how language is shaped by power. It’s through her unpicking of the language around the Dodo that you begin to see how a certain reality or memory of the Dodo is constructed, and how deeply embedded it is in a certain colonial imagination or psychology. I think she was playing with the logic of the language itself, in its ability to shape and define something, its ability to categorise. She was completely blowing that apart and introducing questions, dismantling any idea of certainty or linear temporality. She uses past tense and future tense and present tense all in the same construction, blurring the line between the colonial past and the haunted present.

And in interrogating death, and how we make meaning of death, I see the poet as trying to exploit really limited spaces or cracks in the language to weave something else – maybe a decolonial language. I don’t know if it’s possible, but I think it’s an interesting, generative question that leads to interesting, generative experiments and possibilities beyond the ones we’ve been given. This “mining” is a necessary exercise in expanding our imagination, even if it’s not one hundred percent possible.

And I think that is the point. To see beyond what is already there, or to see the fractures in what appears to be impenetrable. Finding these little ways to breathe within the language and to reinsert herself back in history.

About not/nowhere

In 2018, not/nowhere became custodians of equipment for film production, post-production and optical printing that was formerly managed by no.w.here and originally installed at the north London premises of the London Filmmakers Co-op, an artist led organisation active from 1966 to 1991 producing seminal work out of an aesthetic of material experimentation with 16mm film. As new custodians, not/nowhere embarked on a creative programme of public workshops led by not/nowhere artists and invited guests. On the 5 March 2025, members of not/nowhere, including Habiballa, held an Open Day and welcomed into their studio a full house of artists, curators, educators, and general public all responding to an open invitation to learn about not/nowhere’s analogue operations, their research and timeline for funding to design and construct an architectural solution for a safe and sustainable eco processing laboratory and a chemical laboratory. The onsite event was followed by an offsite research visit to UCL East for further public discussion on creating an ecosystem cartography of production resources available to those using analogue products and processes for artistic expression. The Open Day was supported by University College London’s Community Seeding Fund.

Words Cited

Alsous, Z. (2019), A Theory of Birds: Poems by Zaina Alsous (University of Arkansas Press).

Derrida, J. (1993), Aporias, translated by Thomas Dutoit (Stanford University Press).

Martina Attille is a filmmaker and Arts and Humanities Research Council Techne scholar, registered at UAL Chelsea for her practice-based PhD thesis, Africandescence.

This is an abridged version of a longer interview, edited here for clarity and brevity.