By Jenny Chamarette

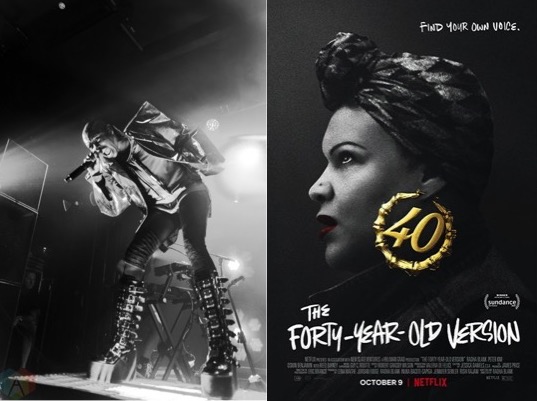

It Takes Blood and Guts by Skin (with Lucy O’Brien) is currently in hardback (£20.00, or £18.60 + shipping on Bookshop.org), in audiobook (narrated by Skin and Lucy O’Brien, prices differ by platform), and ebook (£9.99). If you have a UK library card, you can check OverDrive to see if your library has the audiobook or ebook for loan.

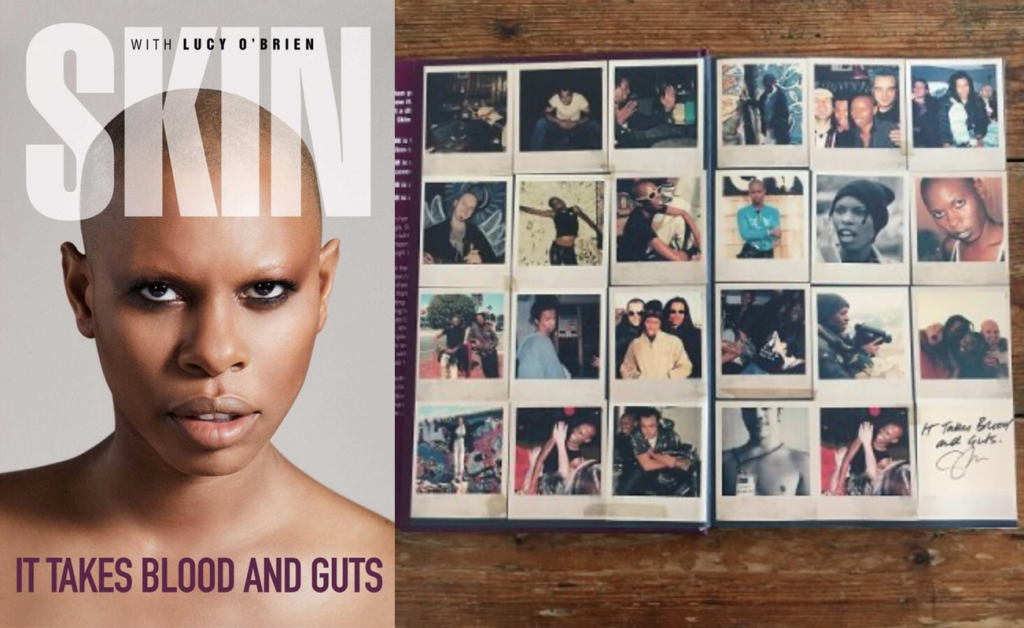

The Forty-Year-Old Version, written, directed by and starring Radha Blank, is available on Netflix UK.

Finding a voice and keeping it

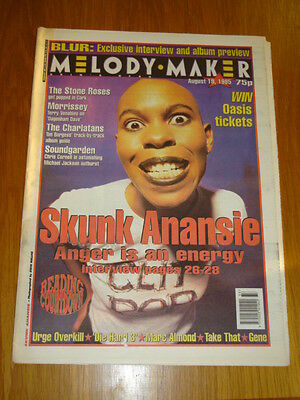

In 1995, I wanted to be a music journalist. I was fourteen: fat, queer, angry, and alone. My home life was messy, and at school I felt suffocated by the latent homophobia that Thatcher’s Section 28 had instilled in every state school in the country. The long-defunct Select magazine was then my music journal of preference: an odd choice when I think on it now, since Select was considered the journal of Britpop — the music movement that Skin scathingly describes in her new autobiography as “a humpback whale […] shooting out a jetstream of floppy-haired white indie bands trying to make it in the USA.” I tried and failed to get into Britpop: even then, something felt tiresomely posturing about those all-male, all-white bands. But I loved Skunk Anansie, Echobelly, and Elastica, and the trip-hop scene that came out of Bristol a few years before Britpop burst. Tricky’s Maxinquaye was a vibrant smack in the chest, dark energy sprawling. Portishead’s sampling took me to another place. And Skunk Anansie’s first album, Paranoid and Sunburnt, let me scream about politics in a way I felt I just couldn’t anywhere else. I didn’t know any other queer people, and I didn’t know many people willing to talk about racism and global politics either.

One of the first things I read about Skunk Anansie was that the lead singer, Skin, was bisexual. Not realizing that music journalism had fallen upon Skin’s sexuality to mark up her difference as a black queer woman in an overwhelmingly white straight rock scene, to me this knowledge felt like a queer beacon shining, giving me new language I urgently needed. And Paranoid and Sunburnt gave me a voice, in a literal sense: my vocal range expanded because of screaming along to it for hours at a time. I’ve never been a singer publicly, but at home I still sing all the time.

Reading Skin’s new autobiography, It Takes Blood and Guts, brings back these memories, and it’s a mixture of pain and elevation to dredge them up. Especially remembering the vulnerability I heard (and still hear) in Skin’s voice as she sang One Hundred Ways To Be A Good Girl: “I caused a major war just by talking/You flew into a rage, cos that’s everything you know.” That fear of violence turned inward spoke directly to my experiences growing up in a dysfunctional family. Skin explains in It Takes Blood and Guts that this was the one track she managed to record in the studio before taking time away to calm severe performance anxiety. I find myself connecting the dots between Skin’s quavering voice, heard by my lonely, fourteen-year-old, queer-girl self in 1995, and the authority I hear in her ownership of that vulnerability as she narrates it in 2020. To say that this gives me feelings is an understatement. I’ve played Skunk Anansie’s first two albums many times over the years, but Skin’s unapologetic tenderness gives me permission to listen again with the raw heartbeat of my inner adolescent.

Skin is admirably honest about the craft and labour of her work as a musician: the three years of songwriting, five days a week, that lead to her forming the bands that eventually lead to Skunk Anansie; the mistakes and the dismissals, as well as the joys. She writes openly about the racism that she and fellow band member Cass experienced within the industry and globally as they toured and travelled, but refuses to allow it to dominate her story. That story powerfully transmits her constant desire to expand her technical repertoire as a music-maker, from her early experiences of music production to her excursions into electronic music and DJing as a solo artist in the 2000s, to the band’s co-production of their fourth and fifth studio albums. There’s also a powerful weaving of political energy and activism throughout the book, from Skin’s early anti-apartheid activism to her participation in education campaigns to eliminate FGM, from attending Nelson Mandela’s 80th birthday party, to becoming a patron of a charity helping child soldiers to heal, to responding through her songwriting to the Occupy movement and the rise of right-wing extremist politics in the 2010s.

I was drawn into It Takes Blood and Guts by my teenage heartbeat; I stayed to learn about the evolution of Skin’s creative expression across music, fashion, film and performance, and her embrace of both grunge and high fashion, pop and rock, guitar and electronic music. I love that she refuses to settle into one mold, and that, at fifty-three years old, she is at peace with this. On songwriting, Skin writes, “Sometimes a song is like a puzzle, a lyrical Rubik’s cube you’re trying to solve, and sometimes it just surfaces, clear and spare and whole.” (p.156) I feel she could be talking about any kind of writing process: finding the empathetic balance between voice and rhythm.

I’ve also found the urge to reconnect to a younger voice in Radha Blank’s self-directed The Forty-Year-Old Version, which uses music, rhyme and writing as tools of agency, self-worth, re-connection to origins and to vulnerability. Blank’s semi-autobiographical film, executive produced by Lena Waithe, was released on Netflix in the UK back in October. The film situates writer-protagonist Radha in mid-life inertia, her first success as a playwright a decade or so behind her. She yearns for critical success, but refuses to provide the performances of “poverty porn” that the cultural whiteness of arts patronage demands from the Black artists it endorses. The Forty-Year-Old Version speaks to the complexity of finding and keeping an authentic creative voice over decades of effort, and the slow-drip racism that frustrates and erodes it. It follows Radha as she enters a new period of creative reinvention, caught between the possibility of a successful Broadway show that eroticises her home neighbourhood into a palatable theatrical hit, and the authenticity she finds in returning to the hip hop rhymes of her adolescence.

Blank’s performance of her semi-autobiographical alter-ego is gentle and exceptionally precise; expansive enough to acknowledge grief in the loss of her artist mother (Blank’s mother also died in 2013), and to hold space on-screen for the tenderness of protagonist Radha’s relationships with her brother, and her gay American-Korean agent and best friend, Archie (Peter Y Kim). Radha’s looks to camera, and the cuts to still images of Blank’s mother’s artwork, and photographs of her younger self, never break time with the rhythm of the narrative. Blank is a brilliant, beat-precise rapper, and a dextrous, beat-perfect filmmaker too. Some reviews have gently critiqued the film for being too sprawling, but I love its refusal to meet the 90-minute metrics of a standard mainstream offering. The Forty-Year-Old-Version’s 123 minutes bolster the sense that it is about Blank’s unique voice in community with others, its generosity of spirit extended towards Harlem as a physical and spiritual home, and the hip-hop artists who uphold Blank in her transformation.

I delight in the body-positivity of The Forty-Year-Old Version— while the on-screen Radha sips weight-loss drinks, her students and her younger lover, D, are amused and bemused because they adore her exactly as she is. And I also love the intergenerational honouring. The soft black and white filming plays upon Spike Lee’s aesthetics for She’s Gotta Have It (for which Blank has writing credits on the television series). Blank honours the contributions of younger BIPOC women to contemporary rap and hip-hop in sequences that include Queen of the Ring femcees and battle rappers. The film does all this with buoyancy, humour and wit, affirming protagonist Radha’s creative paths without a mainstream film narrative of meteoric ascent. The Forty-Year-Old Version wears the lived traumas of racism, sexism, classism and homophobia lightly, refusing to parade them as another version of poverty porn, and instead acknowledging these experiences as the rich and ambivalent embroidery of Radha’s mid-life re-emergence.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that It Takes Blood And Guts and The Forty-Year-Old Version have stuck with me while I experience my own mid-life inertia, as I reflect on the unseen power of my adolescent voice and look to rebuild my own creativity. And it makes sense to me to seek out the wisdom of Black women musicians and artists to do that. Music has the capacity to broadcast internal emotional energies with the intensity of a fire-burst, re-igniting elsewhere in bodies very different to their originators. In the body of a fourteen-year-old queer white girl from the outskirts of London, for instance, when they emanated from the body of a Black bisexual rock frontwoman from Brixton, or a forty-year-old Black playwright/hip-hop artist from Harlem. And in my body now.