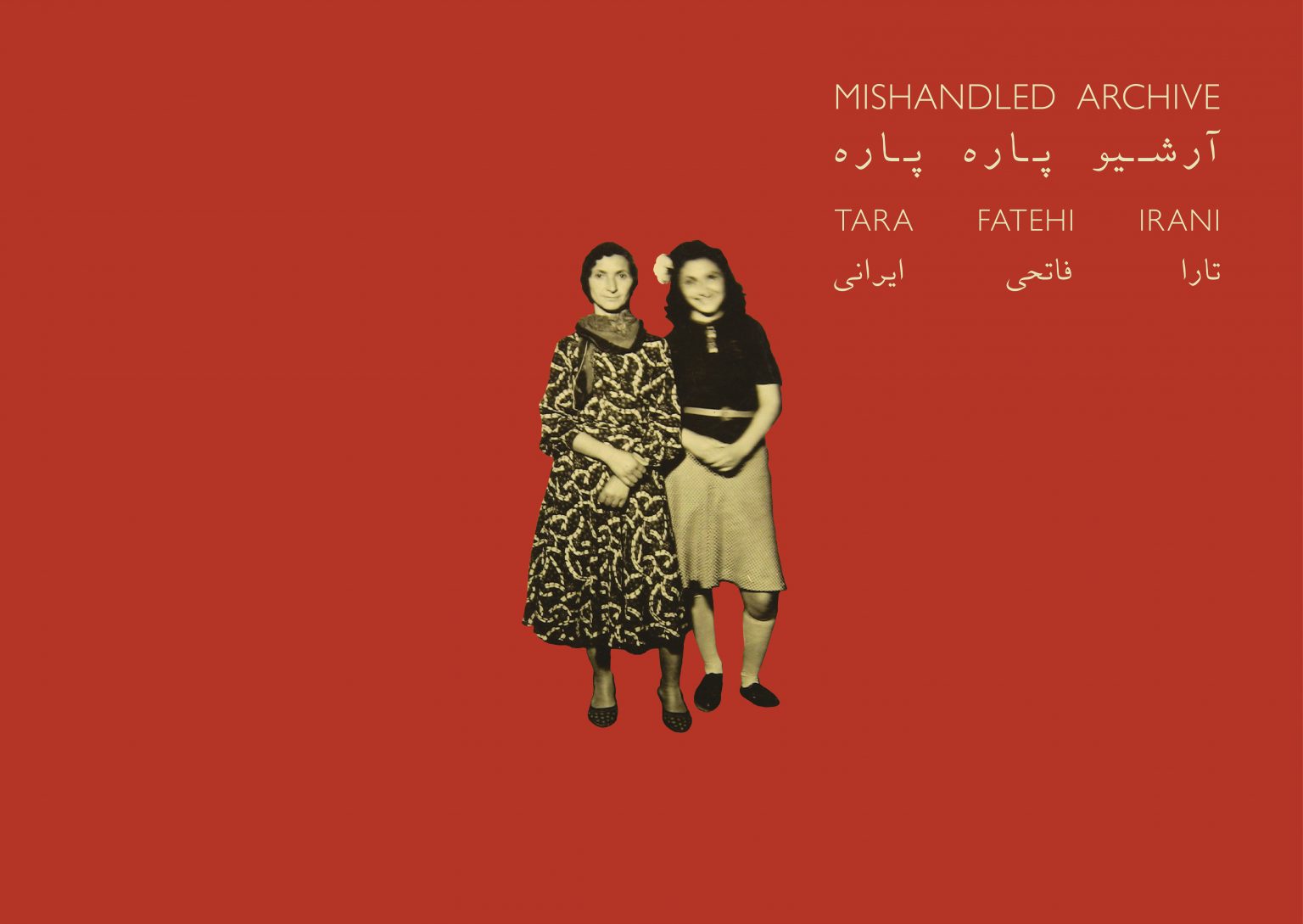

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

Mishandled Archive is a cross-disciplinary project. Learn more from Tara Fatehi Irani’s website, where you can also order the book, including special signed editions. The book is published by Live Art Development Agency (LADA) and supported by Arts Council England.

*

A reading of day 103 – or the deserted, speaking bride

One of my favourite images from Tara Fatehi Irani’s book, Mishandled Archive, is of a bride seated on the floor. She is very still, very quiet, but her eyes speak. Though her head is tilted upwards, her gaze is aslant to her left, to someone other than the photographer – other than the presumed viewer of the finished photograph. She is gazing at her past; she is gazing at her future, at a future waiting, watching, approaching, soon to replace this moment. A future with her lover, with her husband, with herself beyond the veil, bouquet and dress. But let’s not touch this future past just yet; let’s not anticipate what happens next. Let’s stay with this image – or rather let this image stay with us for a while longer, before it disappears in the dunes of time.

When the body speaks, it betrays the cloth that binds it.

Our bride in the brilliant white dress layering out, spreading away from her like sea foam on a darkening shore, sits in the Iranian desert, Rig-e Jenn. How she has come to be here, lifted from the noise of the wedding, the fuss of her family, the prying eye of the photographer, the longing hands of her spouse, is no mystery. Though she sits on a Persian rug (one of those spellbinding carpets whose flowering arabesques and flowing vines tell a different story), she was not carried here by magic. Something tells us this is not ‘a whole new world’ for our bride. And, although Fatehi Irani herself has deposited the photograph and taken a colour version of it in situ, we sense the bride has always been here, that the bridal state has an affinity with the desert. Quietly she sits, her white gloves pristine, a small bag attached to a slender arm, almost invisible in the gathered fabric, a knowing monument. Has the solitude of the desert stolen in already? Its shimmering silence has settled on the crisp folds of her bridal gown, so that the desert is a dress you cannot scale, its slopes and slacks stretching beyond the frame of a photograph. The desert is a dress that wraps and clasps and flows over our bride, holding then releasing her from this moment in time. Sands rush over her, golden sands that have known and unknown and known again Iranian lives and deaths, treating them all to the same glistening fate. Quietly the sun touches each and every grain, aware of the growing storm within, of the life crawling beneath and fluttering above this black and white photograph, nestled in the dazzling dunes of Rig-e Jenn.

Unbind the body and unwind the cloth; both will fall to shreds upon doing so.

What became of the bride when she slipped off the dress, slipped into playing a wife, I do not know. But the double photograph of her (the black and white one captured again in Fatehi Irani’s colour image) dares to defy the obliterating sands of Rig-e Jenn, precisely because of the archival nature of the project. Archives, whether digital or physical, are designed, in part, to ward off the ravages of time, to obliterate oblivion, to resist the loss we all fall perilously close to and endure in the end. Archives traditionally come in protective folders, boxes, cabinets and drawers, their amassed and artificially amalgamated documents and items designed to reconstruct a story, a moment, a life or lifetime that is, in essence, burned or long buried – often in an unmarked grave. But the narratives that historians, curators and archivists create are never the whole truth – barely a fragment of it: they are but one of a myriad of stories, a multitude of moments, a million-fold of lives, like grains of sands, held disparately and desperately together. The gathered ashes of time in an urn that was never its shape.

If the eyes of archives could speak, what would they say? Positioned outwards, their gaze would be aslant to a figure, a memory, a moment, a simultaneous past and future outside the archival box and inventory. Fatehi Irani knows this about archives; she knows that they look, quite often, in the opposite direction to that which the archivist intends. She knows archives speak in multiple tongues, across multiple divides, with multiple intentions; that archives are plural in nature and will continue to be so with every passing, examining, courting, curious eye. She knows that the small form of a bride, found in a family album, then planted in an unfamiliar location, at once says more and less about her than on that original day, when a photographer turned their lens to behold another woman become another wife. In archives, betrothals of all kinds recur on a daily basis; in archives, the bride and the desert meet again.

Out of parts and scraps and dust, the body rises; it is rebound, reclothed, repurposed with the knowledge of this fall and the knowledge of its rising.

Out of the family album our bride flies, to London, to Iran, to Rig-e Jenn, turning the archive outwards, externalising and literalising its inner workings. By taking the photograph of the bride outside of normative archival parameters, Fatehi Irani reveals what the archive should and does and wants to do: traverse times, places, spaces and bodies: confront, resist and eventually embrace loss. Mishandled Archive, a year-long journey around the world depositing photographs and documents from family archives, enacts this trifold process of confronting, resisting and embracing loss across all its archival iterations. Our bride, therefore, has been housed on a digital database, on Instagram, in Fatehi Irani’s bag, in her new book, and, of course, in the sands of Rig-e Jenn. To see our bride in her latest incarnation (book form) does not so much narrate and expose this journey, with all its various transitions and transformations, as crystallise it and attempt to draw our brides – the many brides she was and will become – together again, on and in and through the depth of the page.

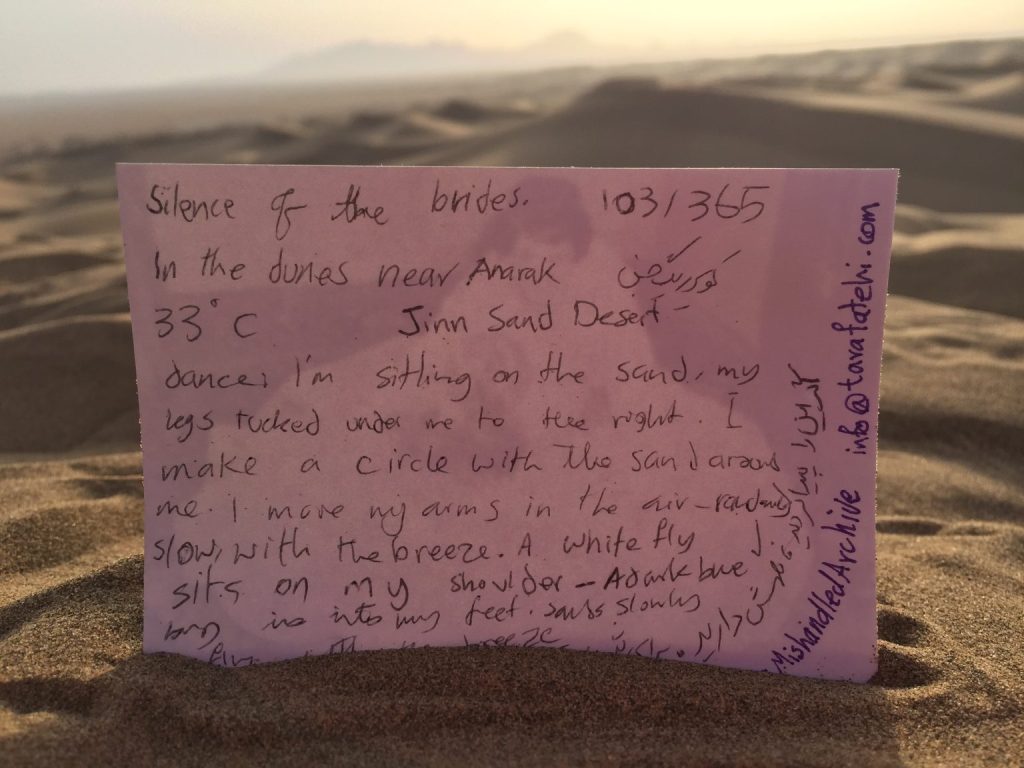

‘Silence of the Brides’, as Fatehi Irani calls this emplaced photograph, fills a whole page of her beautiful multi-landscaped book. Our bride, like the rippling contours of desert surrounding her, stretches and slyly expands on the paper, taking up space in a way that her digitised and Instagrammed incarnations cannot. She is number 103, we are told, of 365 days’ worth of photographs placed in fields, onto tree branches, lampposts, brick walls, table legs, pavements, desks and chairs. Our bride – or this development of her – meets her end – or beginning – in the Iranian desert, but other people, other photographs, are displaced and found on the streets of Peckham, on plane journeys over Lake Como, on the rail of a bridge in Zurich. ‘Silence of the Brides’ exists in 33-degree heat, on the 13thApril 2017, but our bride in the original photograph appears ready to wed in 1950s/60s Iran, in a cooler clime, era and environment than those she eventually migrates to. This is the beauty of Mishandled Archive, in all its manifestations: these bodies, from another time and place, many of whom are no longer alive, still move in their removal to an anachronistic region; they still speak to us, still gaze at and beyond us, and we, in turn, speak and gaze back. Our bride, with her speaking eyes, moving to the nowhere and everywhere, the timeless and time-filled zone of Rig-e Jenn, to the geological boundlessness and existential boundedness of the desert, still speaks, still looks to the side of her and says: ‘I’m where I’ve always been’.

Blown halfway across the world, enduring wars, famine, winds of change, tides of political turbulence, the rebound body begins to unravel again, leaving a strand here, a whisper there, a footprint, a smile, a crumb of a glance at what comes next.

‘Silence of the Brides’ is an enactment, rather than an interpretation, of what Fatehi Irani demands of the archive and her, our, relationship to it. A reanimation of the archive; an inter-connected or inter-invigorative encounter and mode of relating are what Fatehi Irani both proposes and brings about through Mishandled Archive. Using Fred Moten’s concept of ‘appositionality’ (which he defines as ‘an almost hidden step (to the side and back) or gesture, a glance or glancing blow’, as noted in her introduction, p.14), Fatehi Irani encourages and fosters relationships, affective modes of relationality, even on the cusp of detachment, dispersal, distance and disconnection.

Releasing ‘Silence of the Brides’ to the hushed plains of Rig-e Jenn, it is recaptured; in the moment of parting with her, Fatehi Irani, the artist-turned-archivist, and we, the viewer-turned-archival-witness, are reconciled to the bride. Side by side, in this appositional state and act, we, like Fatehi Irani, connect, despite all disparateness. The bride’s side glance, her eyes talking – stepping – to the side – holding true to this line of past and future sight, calls us into this appositional relationship, into her past-now-present state, into a ‘creative’ imagined ‘future’, as Fatehi Irani would have it. The draw of the appositional gaze; the (e)motive pull of the (mishandled) archive.

What of the bodies, unclothed by time, unravelled by misfortune, uncollected, unassembled, unsung and unfound? In the desert you will find them, founders of new lands, reassembled, recollected, recollecting; singing to us in a thousand flickering tongues.

As with each and every photograph (and the odd document), ‘Silence of the Brides’ is accompanied by a dance. This micro-performance is then translated, (an)notated, onto the back of the photograph, a ready invitation for the next passer-by, but also a further archival inscription furthering affective appositional relations. In the book, Fatehi Irani has placed these “scores” next to the image (as depicted on Instagram), complete with an index of hashtags, likes, numbers and information that date this daily mishandling of her archive, differentiating it from those that came before and will come after. These dances are not so much a parodic or surreal reinvention of the minute motions someone goes through when engaging with archives – though they could be, if you want them to be. Rather, these momentary, site-specific choreographies are instinctive responses to and bodily reminders of the emplaced photograph at hand. With her own body, Fatehi Irani honours the bodies visible and visited before her. With her body she reminds us of their bodily past, their conjured bodily present and their fantasised bodily future – and our own. ‘Silence of the Brides’ dictates the performed ritual from start to finish: Fatehi Irani ‘sitting on the sand’ her ‘legs tucked under’ herself ‘to the right’ does not so much as emulate the bride as seek intimacy in paralleling her – the intimacy of imitating a loved one having watched very carefully how and what they do, imbibing it to such an extent that your own body, your own speech, your own left-looking gaze reflects and reproduces their actions, their phrases, their distinct way of being.

Could we say they are the affectations of affective appositionality? Fatehi Irani then makes ‘a circle with the sand around’ her and we are instantly seeing the material ripples of the dress, its seams and encasing panels, extended and taken out to this seamless space of sand and sun. But this circle, Tara’s circle, our circle, with the bride, holds us with her and to her, takes us into the cycle of her life, spanning and circumnavigating together the many stages of an existence, of our existence. As one. Fatehi Irani recalls a ‘blue bug’ by her feet, a ‘white fly’ on her shoulder: life as she knows it in that instance breaks in, cuts the circle, returns us to the little rituals of a ‘silent’ desert humming and teaming with other entities, other experiences. [In squared parenthesis, Fatehi Irani grabs sand, letting it fly into and with the wind – and we recall the wedding, sugar rubbed onto Iranian fabric, the customary superstitions of salt thrown over shoulders, glasses and plates thrown on floors, against walls, confetti poured over newlyweds, the throwing of a party, a celebration, falling excitedly into place once more].

What do these tongues, these bodies, unclothed in silence and reclothed in sound, in singing, say? How can we say the desert is a song-less place when it is brimming with bodies, with people, with lives, as innumerable as the sands that shape it?

From this embodied encounter, our bride is no longer still. She moves in speech, in writing, in type, in her – and our – gaze. Some may see her residing in the desert as a final banishment, as a silencing – the kind of silencing that comes after marriage to a person, an ideology, an occupation, a judgment, a faith. But our bride speaks more loudly from this place, from ancient lands that are ever shifting yet remain; in lands that have been taken up in storms, thrown down and resettled in slaking rivulets of sand, smoothing over what was creased, like a dress, like a bridal gown, like a clothed form of a once shy, now confident, woman. Our bride is wedded to this place of rest and wonder and gold. She looks aslant, surveys all she is mistress over, smiles, softly sings, mingling words and notes and voices with the growing wind around her.