For no reason we can think of, everyone is currently EXTREMELY EXCITED about Belgian-Jewish lesbian filmmaker Chantal Akerman, and about time too! We’ve been reading all about her (again), and wanted to share some of our faves here.

Club Des Femmes screened her sugar-rush second feature Je, Tu, Il, Elle (Me, You, Him, Her) as part of the first ever Fringe! festival in April 2011, and we toured her first-ever film, the explosive short Saute Ma Ville (Blow Up My Town) as part of Revolt, She Said in 2018, screening it with Vera Chytilova’s Daisies, one of Akerman’s own favourite films. Selina Robertson writes about this magnetic film:

‘I always did what I liked and what interested me,’ Akerman said. Patriarchy, repression, depression, subjectivity, wilfulness, revolt: she ripped up the master’s tools. Akerman changed the way I saw cinema, she showed me a way out. My favourite moments are when she bats her eyelashes at the camera. She is only 18, and she will change the world.

She did, and continues to do so. And she started to change the world as early as 1975 – although it was perhaps only (or mainly) feminist critics and viewers that were attuned. As Laura Mulvey recalls in her recent appreciation of the film:

I would like to… go back to my own first encounter with Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles and reflect on the special significance that the film has had for me over the intervening years. I first saw it at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1975 – a year remarkable for the energy and fertility of experimental film, as it veered between an extreme art cinema and an actual avant-garde. The films shown included, from the United States: Film About a Woman Who… and Lives of Performers (both Yvonne Rainer), What Maisie Knew (Babette Mangolte – Akerman’s, Rainer’s and later Sally Potter’s cinematographer), Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen(Michael Snow) and Speaking Directly (Jon Jost); from the UK: The Amazing Equal Pay Show (London Women’s Film Group) and Nightcleaners (Berwick Street Film Collective); and from Europe: Moses and Aron (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet) and The Middle of the Road Is a Very Dead End (Alexander Kluge and Edgar Reitz).

Alongside these films, all remarkable in their different ways, Jeanne Dielman stood out as something completely new and unexpected. It was the film’s courage that was immediately most striking. Akerman’s unwavering and completely luminous adherence to a female perspective (not, that is, via the character, Jeanne Dielman, but embedded in the film itself and its director’s vision) combined with her uncompromising and completely coherent cinema to produce a film that was both feminist and cinematically radical. One might say that it felt as though there was a before and an after Jeanne Dielman, just as there had once been a before and after Citizen Kane.

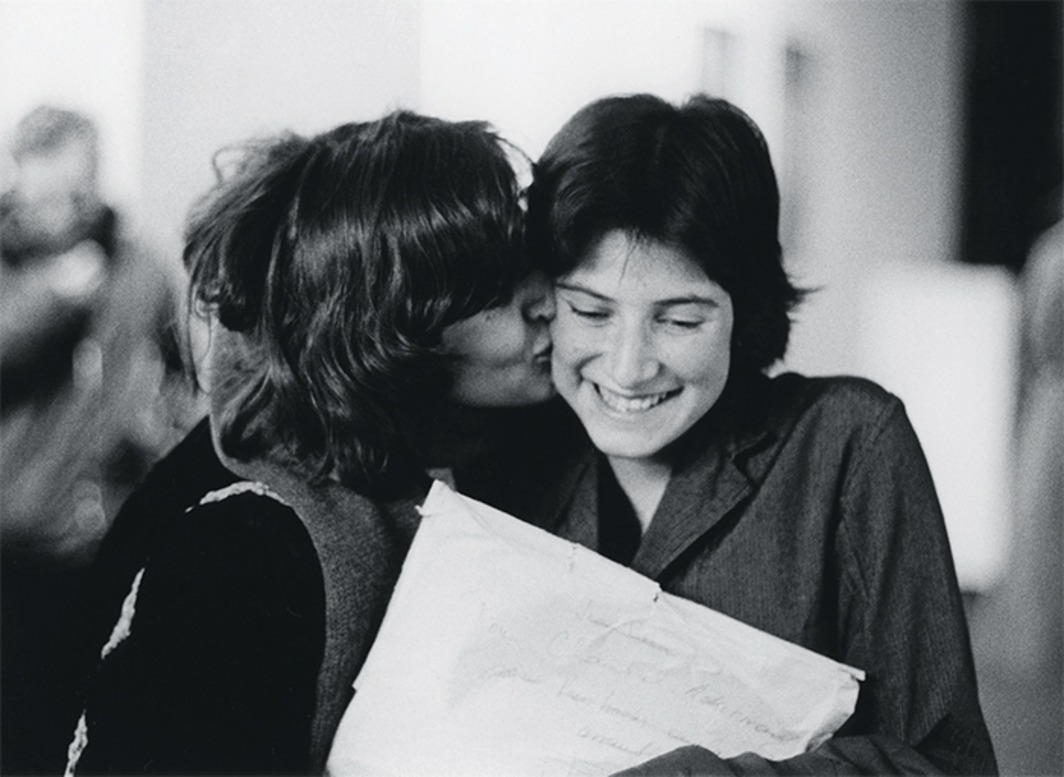

Of course, the legend that is B. Ruby Rich also knew that Akerman was a world-changer as early as 1976, when she conducted an epic interview with her for Video Data Bank in Chicago, recently set up by Rich’s neighbours Kate Horsfield and Lyn Blumenthal, who captured the event on Portapak video for posterity. You can read the whole interview [PDF] which was transcribed as part of the Akerman dossier that Rich edited as a tribute to her friend after her shocking death in 2016.

In the interview, Rich and Akerman negotiate Akerman’s complex and changing relation to the words ‘feminist’ and ‘lesbian’, a negotiation that Rich prefaces by noting that Akerman’s reception within feminist film circles had been electrifying and possibly overwhelming. She writes that:

Chantal was certainly a figure to champion: tiny, impossibly young, full of passion and genius, and, as rumor already had it at the time, a lesbian. Certainly, she went on to center her life around women and a selection of exceptional male collaborators. Foremost were her mother and aunts, whom she so often referenced and who deeply influenced her work. There was [Jeanne Dielmann star] Delphine Seyrig, whom she’d meet for breakfast day after day, week after week, until her death from cancer at the age of 58. There was her longtime producer, Marilyn Watelet, first glimpsed that week in Chicago when she flew over from Brussels to stay at my loft with Chantal; her longtime editor, Claire Atherton; and of course, her life partner, the cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton, who so deeply influenced her life and cinema.

Akerman’s commitment to building film family and her evasion of fixed labels may not be contradictions, but perhaps both related – as Leshu Torchin notes in her nuanced reading of Jeanne Dielmanas a Jewish film– to Akerman’s mother’s family’s experience at the hands of the Nazis, the shifting subject of her final film No Home Movie. As Torchin writes,

The relationship of Belgian Jews of Chantal Akerman’s generation to Belgium is a fraught one… [A][ cloud of sadness, adjustment, and instability surrounded [them]. Arguments for their non-Belgianness were pervasive. They had come from D’Est where war destabilized all national boundaries. My mother’s answer made it clear ours was a different national story, especially from the perspective of her generation.

When I saw Jeanne Dielman for the first time, I recognized my own experience. I was 14 or 15 years old. I went to the Brattle Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, intrigued by the description of the film, which focused on a Belgian sex worker. What I saw was unexpected. I was entranced even then.

The mise-en-scene evoked the meticulously managed homes I knew. It is hard to know whether my family dedicated themselves to this intense organization of space to ensure belonging or to stave off the trauma infusing the corners of their lives.

A kaleidoscopic, world-making filmmaker who revolted against all boundaries and blew up all towns, we hope and know that Akerman will continue to be watched and written about in ways that continue to nuance and expand our understanding of her work, as she nuanced and expanded our understanding of the world. And we will keep screening her films!

Want to read more & more? We recommend A Nos Amours’ handbook that collects their incredible Akerman 2013–15 screening programme, edited by ANA founders Joanna Hogg and Adam Roberts, and described by Sandy Flitterman-Lewis as ‘an actual monument in and of itself, one that memorializes and celebrates a body of work and a cinematic auteur in an enduring way.’