By Sara Chambers

To chase down the books in this post, we recommend OverDrive for local library audiobook titles, and Bookshop.org for all titles in print (all 10% off): here’s a Mavis Doriel Hay for starters. For out of print titles, AbeBooks can be a good source of affordable used books. Happy hunting!

*

SOME MUST WATCH, OTHERS WILL READ

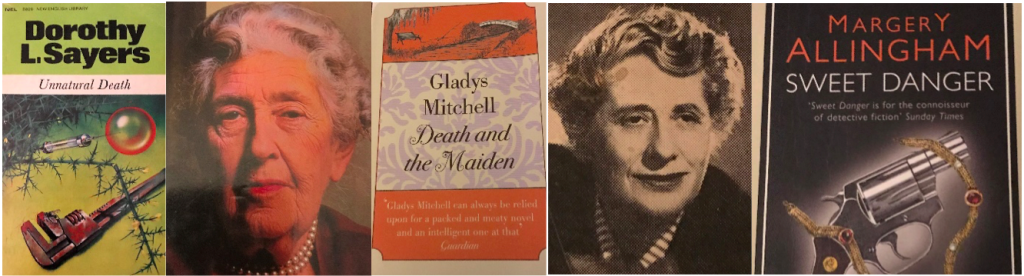

Developing my crime fiction addiction from the largely American female contemporary private eye novels, I gravitated towards that mainly British crime sub-genre I’d previously rejected: the ‘Golden Age’ mysteries. Taking a forensic approach, I started with the classics; queens of the period like Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham and Gladys Mitchell. Then, moving deeper into the margins of neglected female writers of this era I discovered I was hooked and actively sought out new names.

Often dismissed by the literary establishment, and other crime fans as ‘cosy crime’, I found that the sparseness of gore, something that some modern crime novels wallow and bathe in, a refreshing change. Of course, nasty deaths and vicious killers do populate the novels, but vivid descriptions of a serial killer’s/rapist thinking, or pages outlining gratuitous violence against women are not found here. But wicked, dangerous, devious, craven and venal characters are found aplenty and are generally, and satisfyingly, brought to justice.

Not for these books the modern preoccupation with lauding the anti-hero serial killer, who is always much smarter and intelligent that those chasing them; evading justice for years so that they can continue to kill and kill again and again. Not that the plod or private investigators in these mysteries are naturally superior to the killers, just that the murderers, however ingenious, are always tracked down by patient and intelligent detection. Well, OK, private investigators like Miss Marple and Miss Silver are more intelligent than the police, so much so that there is a grudging official acknowledgement of their superiority in exposing the culprit. Speaking as someone middle-aged and looking forward with slight trepidation, I say ‘Yay! Viva the old bags!’

But what about claims that these books contain racism and snobbery. Well, not every story is set in a country house, far from it, and not every book is rife with prejudice. Of course, there are unacceptable examples where derogatory words are used, but not everywhere. An air of general dismissiveness towards ‘foreigners’ can sometimes be detected, but as Linda Semple and Rosalind Coward note in their front piece for the Pandora Women Crime Writer books,

it is a popular misconception that all earlier novels are always snobbish and racist… many… authors managed to avoid, sometimes deliberately, the prevailing views. Others are more rooted in the ideologies of their time and when their remarks jar, it does serve to remind us that any novel must be understood by reference to the historical context in which it was written.

If that sounds like damned by faint praise, I want to reassure you, dear reader, that there are plenty of reasons to read on. Yes, realism in plots and murders may not be always present; how can villages be full of so many murderous types? And how many more ingenious ways are there to kill? But, when was crime fiction ever ‘real’? (There’s a clue in the word ‘fiction’). Settings may be old fashioned, but by and large enjoyable escapism is the order of the day. In these Golden Age whodunnits there are occasionally vivid descriptions of working class poverty, upper class drug addiction, menacing cults, and the awakening of sexualised young women, but nothing that veers into anything too upsetting! Instead, the content of these crime stories helps paint a picture of the privations, activities and anxieties of the time they were written; post the Depression and the Second World War. Not much ‘cosiness’ there!

So, we’ll not go over old ground and write about those authors you may be already familiar with, but rather those you’re not. I’m not a critic, can’t claim to have read every crime story written by woman during the 30s, 40s and 50s, but would just like to share a selection of titles by those either languishing in obscurity or neglected because they’re seen as old fashioned.

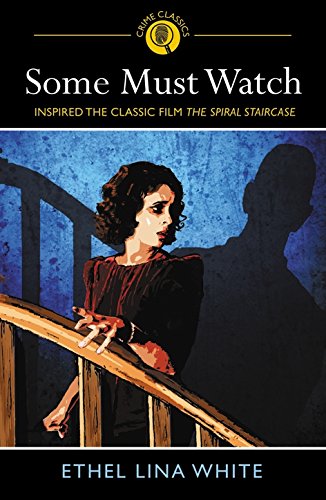

Ethel Lina White was one of eight children, born in Abergavenny in 1890. She attended art school and took up writing after quitting her job in the Ministry of Pensions. She was a popular writer in the 30s and 40s – you may be familiar with Alfred Hitchcock’s 1938 film The Lady Vanishes which was based on White’s The Wheel Spins. Interest in filming her books increased, and in 1946 Robert Siodmak directed The Spiral Staircase. The film, based on White’s 1933 book Some Must Watch, shows a homicidal maniac killing disabled women and who attacks the mute heroine. Close, but not quite on the money I’m afraid. The novel, one of my all time favourites, is a blistering examination of pure, murderous misogyny; it’s not only female disfigurement that the murderer is repelled by, but any young women who has the misfortune to fall in front of this scumbag’s gaze. As the book’s heroine Helen finds herself almost alone in the house, she realises that she’s trapped inside with a killer. Trapped, but not quite facing the murderer alone… The dénouement feels like an understanding that women have to take matters in their own hands; vicious killers need to be put down. Dead.

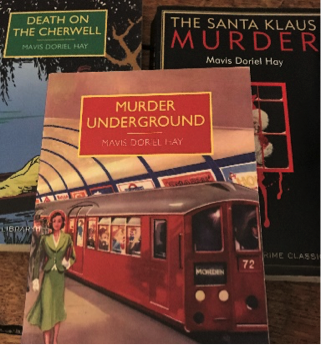

Mavis Doriel Hay didn’t have a very extensive output; only three crime books (which have been handily republished by the British Library under their Crime Classics imprint). Born in Potters Bar in 1894, Hay attended St Hilda’s College, Oxford and later published a number of works on handicrafts, especially quilting. However, during the thirties she wrote three mystery novels. For me the best was her first, 1934’s Murder Underground. The story involves the death of an unpleasant resident of a private hotel in the local underground station. Dorothy L Sayers was a fan, noting that the book featured a character called Basil, “one of the most feckless, exasperating and lifelike literary men that ever confused a trail.” The feckless Basil, led by the “trim and alert” Betty, endeavours to discover who killed Basil’s unlikeable Aunt, together with helpful tips from various residents of the hotel.

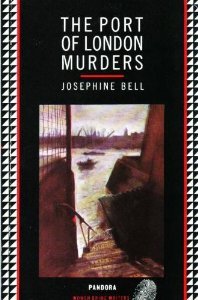

Doris Collier, born 1897 in Manchester, was a GP in Greenwich when she started writing. Using the pen name Josephine Bell, she began writing crime novels, many of which made reference to medicine. Forty odd books mark the impressive output of someone who was there at the beginning of the Crime Writers Association (CWA), an organisation whose ‘Golden Dagger Awards’ are the UK’s top crime writing awards, and was chair 1959-1960. The Port of London Murders, written in 1938, features a dodgy doctor working amongst a backdrop of sordid poverty along the river Thames in south east London. Amid the description of the pernicious effects of drug addiction amongst the middle classes and the vivid portrayal of life in soon-to-be-condemned squalid housing, the reader encounters a nasty murder dressed up as an accident, and the shocking disappearance of the investigating detective. And what does the finding of boxes of fancy negligées washed up in the tide have to do with anything?

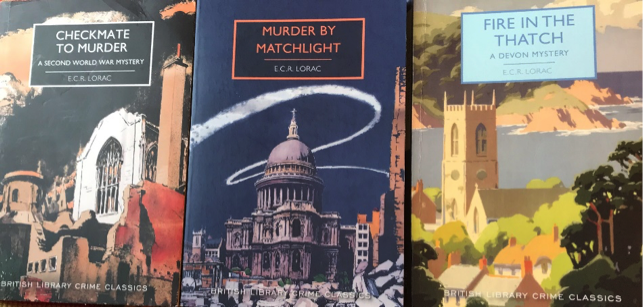

E C R Lorac was one of the pen names of Edith Caroline Rivett, a prolific writer of crime fiction between the 1930s and 1950s. Other names she used were Carol Carnac and Mary Le Bourne. Born in Middlesex in 1894, she published her first novel in 1931. Fire in the Thatch, which came out in 1946, is as Martin Edwards describes in his foreword for the British Library re-issue, “an enjoyable example of E C R Lorac’s ability to impart a distinctive flavour to the traditional detective story.” Using her regular detective, Inspector Macdonald, this Devon-set mystery set during the Second World War paints a striking portrait of a rural setting blighted by a terrible event. Bats in the Belfry, Murder by Matchlight and Checkmate to Murder are all set in roughly the same area of north London, although Lorac did set other novels in Lancashire, were she later settled to be with her sister. She remained unmarried.

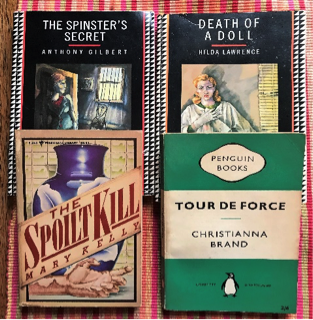

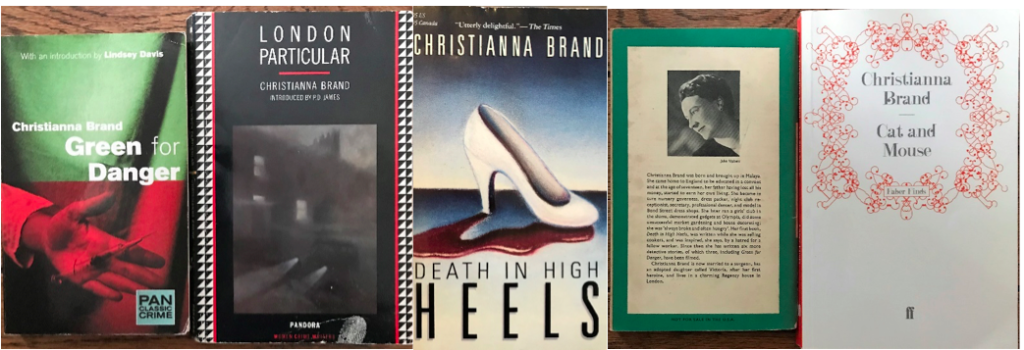

Christianna Brand, born Mary Christianna Milne, may be familiar as a children’s writer – she wrote the Nanny McPhee series – or as the author of that oft-shown crime film classic Green for Danger. But her other whodunnit novels are well worth exploring. With a background of working in a variety of jobs, Brand used her experiences to good effect in her first novel Death in High Heels (1941), set in a high class ladies dress shop. In that book and her novels London Particular (1952) and Cat and Mouse (1950), Brand explores the lives of sexualised young women. Not in a scandalised way, certainly by modern standards, but quite refreshingly different to those found in other ‘Golden Age’ novels. In London Particular, the effect of one young woman’s actions in finding herself pregnant produces a murderous reaction on a weak minded man, hopelessly in love with her. In her novels, Brand seems to understand that men, including often the inspectors leading the investigation, would find the young women they encounter attractive. But their interest is always understood by the women themselves in a way to suggest they have the measure of any of the men they have to deal with, and that this is an occupational hazard.

In contrast to Brand, author Patricia Wentworth’s background appeared to be far removed from someone having to do a variety of jobs to help make ends meet. Born in India at the time of British rule, Dora Amy Elles’s father was a General and her mother a Lady. After her second marriage to another military man, Elles started writing, adopting the pen name of Patricia Wentworth. Her output was fairly prolific, with over 32 titles with the private investigator Miss Silver, and another forty odd other titles. Similarities with the Miss Marple character can be made. Neither of them have any sex life to speak of, although Miss Silver is slightly younger and once worked as a private inquiry agent, whereas Marple just often happened to be on the spot at the right time. Despite her traditional plots, Wentworth like Christie often explores the dark underbelly of village life, albeit in a very genteel way. Miss Silver Comes to Stay (1949) and The Watersplash (1951) are prime examples of something nasty lurking amongst the pretty surroundings of a fictional village. The books often feature a brooding young man, whose love interest is overlooked, until Miss Silver unravels the murderous entanglement and true love can begin to blossom.

Similar to Miss Marple, Maud Silver often enjoys handy invites from old school friends to stay conveniently in the area where a murder is about to take place. Being friends with the chief constable (she was his governess) is useful for a direct in on the investigation, and a big plus as the private enquiry agent is soon able to discover information that the police can’t, mainly because she knows that the best gossip is always gleaned through domestics – housekeepers, cleaners and cooks etc.. Regular readers may note, with either irritation or pleasure, that Miss Silver is forever knitting vests for friends’ babies, and coughing gently in conversation. This latter affectation was obviously something that readers of the time commented on as in the foreword to The Catherine Wheel Wentworth writes,

To those readers who have so kindly concerned themselves about Miss Silver’s health. Her occasional slight cough is merely a means of self-expression. It does not indicate any bronchial affection. She enjoys excellent health.

Finally, I would like to draw attention to an important maxim, expressed by Miss Marple, that can be applied to these troubled times. In Sleeping Murder, Miss Marple explains to a credulous couple at the centre of a murder plot that it is important not to believe everything you are told:

You believed what he said. It really is very dangerous to believe people. I haven’t for years.

Today, where people often believe everything they’re told or read, it’s time to engage our brains and evaluate information with a cool, clinical detachment as Miss Marple or Maud Silver might. Viva the old bags, indeed!