By Hyun Jin Cho

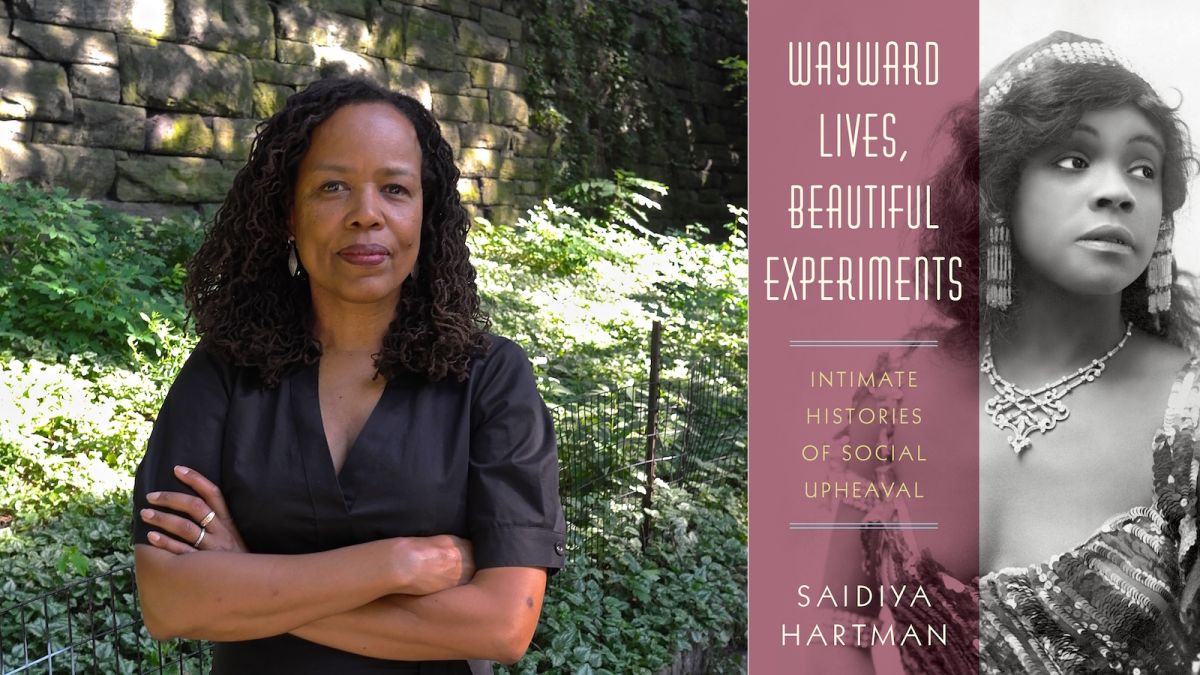

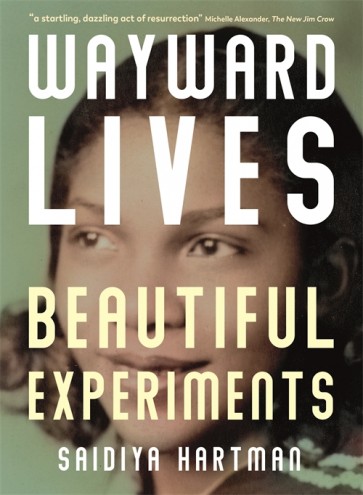

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals is available now in paperback, ebook and audiobook, read by Allyson Johnson.

You can order a print copy from an independent black-run bookstore (UK, North America) (check whether they are offering mail order during closure), or get the print or ebook direct from the UK publisher Serpent’s Tail. If you UK have a local library card, you can check Overdrive to borrow, waitlist or request the ebook or audiobook.

She has just finished reading Saidiya Hartman’s new book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments for the second time alone in her room. Her daughter sent the book to her with a note explaining that she had received it as a gift for her fortieth birthday, read it and wanted to share it with her. She knows that her mum appreciates stories that are told by marginal voices and understands the profound beauty of ordinary lives. This beauty makes her think of her late mother who was indeed a fearless innovator of her own daily existence.

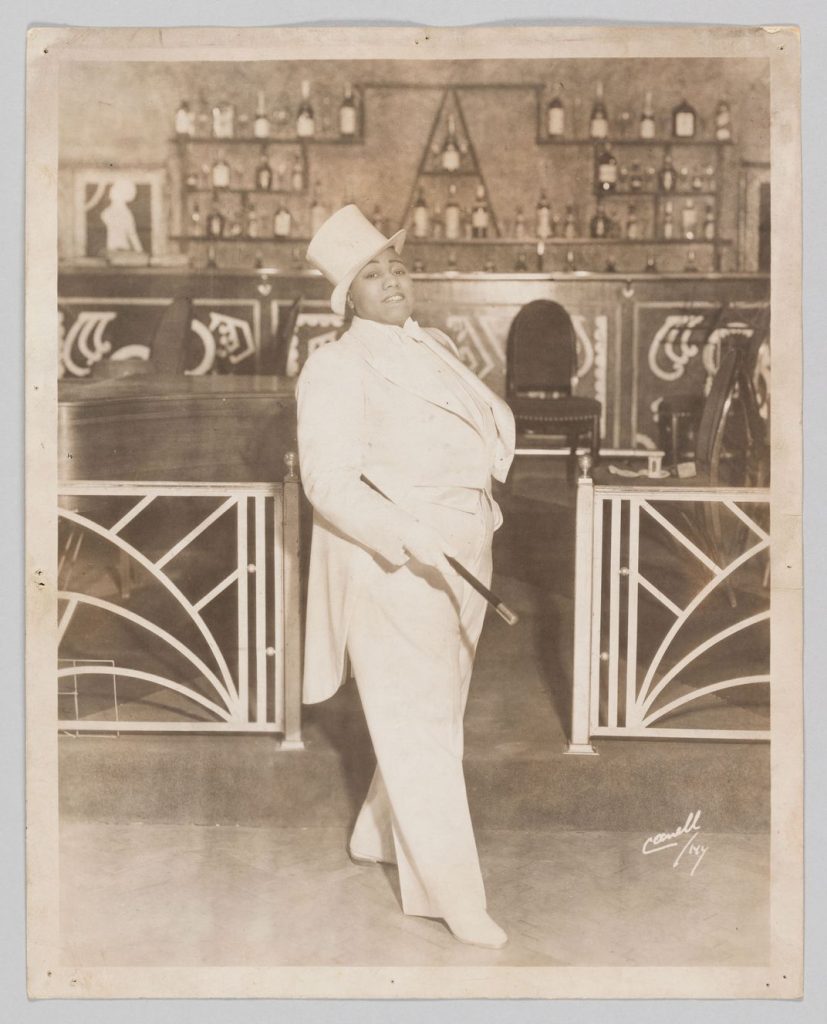

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments is a detailed, sensitive, radical historiography of how young black women living in Philadelphia and New York at the turn of the twentieth century pursued liberty. They were never meant to survive but they did so, resisting the enormous brutality imposed on them by the chronic racism of the state and inventing new social norms of sexuality, kinship and the parameters of intimacy. Starting from one studio photograph of an anonymous young girl, the book becomes a portrait of the chorus narrating the intimate lives of Mattie, Ida, Mamie, Harriet, Esther, Eva, Mabel and their collective endeavours to live free in the confines of the carceral landscape.

Mattie wanted something else. It was as simple and elusive, as vague and insistent as that. Something else was never listed as one of the reasons people left home, only the appalling and the verifiable – the boll weevil, lynching, the white mob, the chain gang, rape, servitude, debt peonage; yet the inchoate, what you wanted but couldn’t name, the resolute, stubborn desire for an elsewhere and an otherwise that had yet to emerge clearly, a notion of the possible whose outlines were fuzzy and amorphous, exerted a force no less powerful and tenacious.

She remembers the day she started the book, the first Saturday after the lockdown was imposed. The idea of freedom appeared in our daily conversations more than ever, and later we saw some protests against the lockdown, and its supposed suppression of civil rights, with slogans such as ‘freedom over fear’. She is aware of how often she uses that word: freedom. It is something that crosses her mind, something she desires, perhaps even more so as she got older. An elsewhere and an otherwise.

Reading the book, she began thinking about the radically different contexts in which this word, this longing, can emerge. She is imagining the freedom Mattie and other wayward girls wanted. To get away from the state surveillance and police power that regulated even the most intimate aspects of their lives and that allowed them only one role: servility. Their small rented rooms became a laboratory for trying to live free in a world where freedom was thwarted, elusive, deferred, anticipated rather than actualised.

Suddenly she feels nauseated by the clunkiness of our language: how can one word bear the weight of all these possible discrete significances? There were many words in this book she had to look up in an English dictionary – carceral, tumult, gawk, drudge, vagrancy, orifice, stench, hussy, excrescence. She had to pause to be introduced to the efficacy of each word, negotiating each’s rich social and historical terrain. Hartman’s visceral narrative, filled with voices and use of the words of wild young women, deepens and disturbs our sociological understanding of this contested period.

She was hungry for beauty. In her case, the aesthetic wasn’t a realm separate and distinct from the daily challenges of survival; rather, the aim was to make an art of subsistence. She did not try to create a poem or song or painting. What she created was Esther Brown. That was the offering, the bit of art, that could not come from any other. She would polish and hone that. She would celebrate that every day something had tried to kill her and failed. She would make a beautiful life. What is beauty, if not “the intense sensation of being pulled toward the animating force of life?” Or the yearning “to bring things into relation … with a kind of urgency as though one’s life depended upon it.” Or the love of the black ordinary? Or the capacity to make what we do and how we do it into sustenance and shield?

She is reminded of Audre Lorde’s writing on care and the erotic, feeling that Hartman’s care-full and erotic connection to these women is an ethical deed. Esther’s offering is only possible because of her capacity for feeling, a deep and irreplaceable knowledge of [her] capacity for joy. Lorde says the erotic is a guiding light towards any understanding, both of herself and with others. Yet, alone in her room she acknowledges how difficult it is to exercise this – to yield, to be undone and dispossessed by the force of her desire – and to be moved by it when performed by others.