By Lucy Howie

Editor’s note: This is part of a series of reflections on the political aesthetics of 1980s inclusive queer feminisms, alongside Jack Thompson’s essay on REBEL DYKES, Irenosen Okojie’s meditation on A PLACE OF RAGE, and Jacob Engelberg’s bisexual look at SHE MUST BE SEEING THINGS.

We’d also include the Culture Club conversation between filmmakers Lizzie Borden and Jessie Rovinelli, which speaks to the resonances between then and now, and why it’s important to value and re-evaluate the radical work of the 1980s.

Some of you might have come to the Rio in November 2017 to watch and discuss Jacqui Duckworth’s films with us. If you’re interested in seeing Jacqui’s work (again): our friends des femmes, the volunteer-run organisation Cinenova, are currently seeking funds to digitise, preserve and share their incredible archive: please consider donating to or joining their Supporters’ Scheme.

*

Sitting in the Cinenova online archives is the work of lesbian, feminist filmmaker Jacqui Duckworth, whose semi-autobiographical film A Prayer Before Birth (1991) has remained untouched by secondary scholarship. I felt a sense of urgency in writing on Duckworth, whose name I had not encountered before and is one that could so easily disappear from contemporary lesbian feminist collective consciousness. A Prayer is startling in its dislocating but enthralling moving image sequences, chronicling Duckworth’s lived experience with multiple sclerosis (MS) to tackle entangled questions of subjectivity, disability and desire, all in the space of nineteen minutes. In A Prayer not only does Duckworth foreground lesbian subjectivity, as she had in earlier works such as Home Made Melodrama (1982) and An Invitation to Marilyn C (1983), but she also articulates a visual language to represent the non-healthy body. Taking on strategies of Surrealism and American Avant-garde film, Duckworth uses non-normative narrative in the film to escape the limitations of ‘positive images’ of disability and lesbian identity. This modified surrealist aesthetic reflects ‘an increasing sense of unreality’ and produces new realities to grapple with the psychological and physical traumas that MS induces.1

As part of the 2017 Fringe! Queer Film & Arts Fest, Club des Femmes and Felicity Sparrow organised a day of screenings at the Rio cinema, paying tribute to Duckworth as a pioneer in the new lesbian feminist film aesthetic, marking out the context from which I have read her work. A Prayer featured as a photo-essay in the ground-breaking exhibition Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs (1991), curated by Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, evidencing Duckworth’s explicit participation in photo-theory debates from the UK in the 1970s and the new lesbian feminist aesthetic of 1980s and 1990s London. Laura Guy has written on the intervention that lesbian representation and semiotics made in photo-theory debates that continued into the 1990s, positing that the inseparability of representation and sexuality and the denaturalising of lesbian identity could generate the same for the medium of photography.2

Intervening at this intersection of photo-theory and political activism, Stolen Glances and A Prayer pose a challenge to film and photography’s accepted correlation to the ‘real’. Much of the work in Stolen Glances featured co-opted images from a social imaginary of the past to re-write conventional heterosexual narratives, weaving in fragments from the past to form images constituting an emerging lesbian feminist aesthetic. Boffin’s series in Stolen Glances, The Knights Move (1990), demonstrates this, taking issue with the prioritising of reality over fantasy, instead avowing to use photography’s claim to the real, to make lesbian fantasy possible. These ‘backwards glances,’ as Guy puts it, that use the past as an imaginative space for lesbian identity to unfold, offer a touchstone for Duckworth’s A Prayer. Adopting a modified surrealist aesthetic, Duckworth uses referentiality as a mode of lesbian representation, and as I argue, consciously cites Maya Deren (and Alexander Hammid’s) Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), repurposing its motifs to represent the lesbian and disabled body.

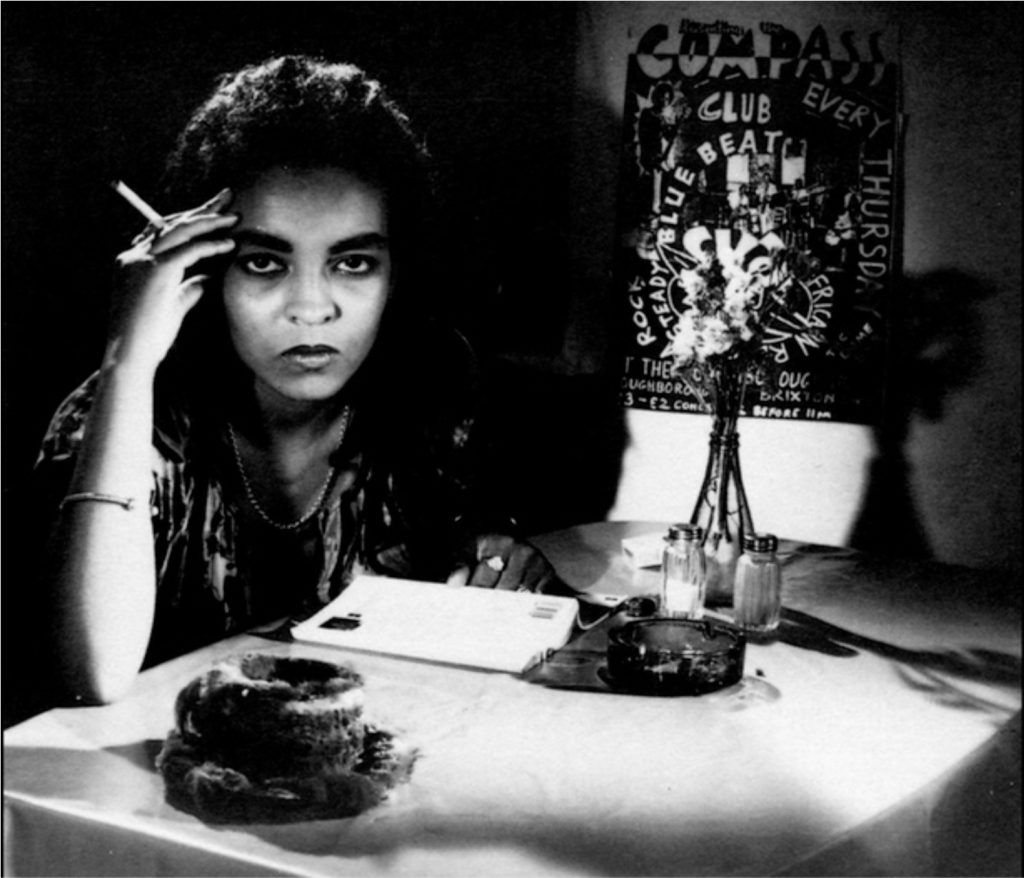

The third still from Duckworth’s photo-essay Coming Out Twice in Stolen Glances, shows a black and white image of Marsha, the film’s subject, captured looking directly into the camera lens, accompanied by the following text:

She experiences the unreality

of everyday things made strange.

Does she imagine the flea

which crawls out of the fur cup and saucer

and hops with great vitality beyond her reach?

The fur teacup and saucer described in the text is located in the foreground of the still. Likely citing Meret Oppenheim’s Object (Le Dejeuner en Fourrure) (1936) that plays with patriarchal fetishes of the female body around fur, vessel and woman’s sex, Duckworth establishes a set of productive citations.3 Object is an apt citation for a context that frames lesbian subjectivity in a socio-political atmosphere of homophobia and Section 28, considering its fetishistic connotations with oral sex that stages the Surrealist paradox between repulsion and desire. Duckworth’s citation of the Surrealist object functions as a form of lesbian representation pertaining to desire and possibility. Redeploying the uncanny art object in the film still signals Duckworth’s uptake of Surrealist objects and images like mannequin bodies, shattered glass, and mirrors in the moving image that pushes at the dislocating, psychological experiences of disability. This Surrealist sensibility is also reflected in Duckworth’s staging of a ‘vision in crisis’ that signifies the violence of looking if the eye or camera is to be revered.

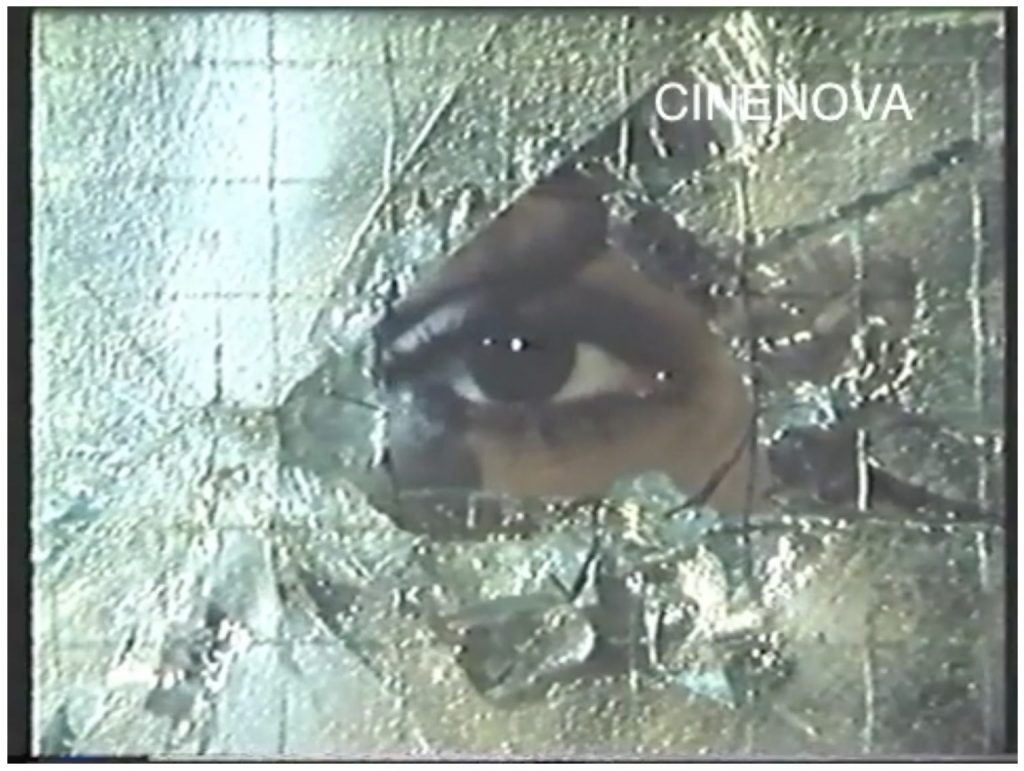

A Prayer is structured by sharp cuts between disparate shots that shift from scenes suggestive of an able-bodied past, to stylised dream-like passages that speak to various kinds of interiority. Duckworth sets up what I call a ‘vision in crisis,’ whereby there are frequent slips between the object of the camera’s gaze and the perspective of Marsha, as well as the staging of relational encounters across multiplying iterations of the self in the film. This crisis of subject-object relations shores up a discourse on ‘looking’ and encountering oneself that strikes parallels with the sense of unreality produced in Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, and grapples with the protagonist’s shifting notion of self as lesbian and disabled subject. Following the opening sequence, there is a closeup shot of Marsha’s eye seen through a fractured pane of frosted glass.

This image signifies the violence of vision that the film interrogates, chiming with but ultimately transforming the notion of vision in Deren’s film into a discourse on ‘looking’ as a relational encounter of desire and learning to love oneself. Understood within a logic of violence, the vision in crisis in Meshes culminates in the shattering of the mirror (man’s image), following an intense sequence of shots that move between the protagonist’s subjective point-of-view, images of Maya as the camera’s object and a perplexing closeup of her eye. The shattering of the mirror has been read as a literal reaching out ‘to control the definition of her self’ against male sexuality and narcissistic female sexuality, preceding the final image of the protagonist’s death with shattered glass on her lap.4

Duckworth uses a similar set of relations across various iterations of the self, to instead depict Marsha learning to see herself as she really is post-diagnosis and deal with the effects on sight from MS.

The cultural theorist Kaja Silverman offers an ethical framework which she terms the ‘productive look’ that seeks to undo acts of violence that are produced within the dominant field of vision through the ‘productive’ that is a conscious idealisation of the ‘Other’ as other.5 This formulation of looking resonates with Duckworth’s film foregrounding representation and ‘otherness,’ to consider how we might productively look at the subject culturally inscribed as ‘other.’ I continue Silverman’s formulation of the ‘productive look’ to consider Duckworth’s concern with vision in A Prayer, arguing that the film is a meditation on encounter, relation, and desire. Duckworth’s film can be considered within this ethical logic, as Marsha encounters herself through the self, to depict the lived experience of the body that in heteronormative and ableist society is ‘other’. Notably Silverman’s formulation that challenges encounter through ‘self-sameness’ is complicated by Duckworth in the staging of the self as both subject and object; able-bodied and dis-abled.

The photographic studio sequence in A Prayer succinctly brings together the film’s subject-object relations of the self, where Marsha encounters multiplied iterations of herself as other to consider the limits and possibilities of looking. The sequence begins with a closeup of Marsha’s eye, followed by a shot showing the back of a semi-naked female model.6 The camera looks ‘as’ Marsha in the bygone space of the photographic studio, with the image of the model as seen through Marsha’s camera and obscured images of flashing spotlights that indicate early visual symptoms of MS. The camera then abruptly moves to looking at Marsha in the present as the camera’s object, viewed from behind, looking through the pane of frosted glass. Finally, vision is disrupted again, and a third perspective completes the triangulation of ‘looks,’ with the camera seeing ‘as’ Marsha in the present encountering herself in the photographic space. Duckworth subverts ‘the male gaze’ with woman as photographer and model, while also merging the cinematic vision in crisis with physical realities of vision challenged by disability.7 Moreover, through the logic of the voyeur that is established by the narrative of photographer, and by the protagonist looking through the glass, Marsha comes to see herself as desirable through active looking and the idealisation of the self as other. Duckworth repurposes Deren’s construction of vision that stages terror and dislocation, transforming this set of interrelations into the ‘productive look’. In seeing the self as doubled and tripled, Marsha finds the self beyond constructions of otherness produced through ‘self-sameness’.

As well as the choreography of the camera between subject-object relations in Meshes, A Prayer borrows the exchange of interior/exterior that is central to the recursive narrative structure of Deren’s film. As Marsha works her way through various rooms in the building, a hospital- or school-like space that is vacant and bare, Duckworth redeploys the recursiveness of Meshes whereby the protagonist repeatedly opens, closes and looks through doors that continually return to a central corridor space and a barren, blue room. Modifying the progressively entangled structures of Meshes, Duckworth transforms a narrative that deals with gender and the domestic sphere into one that sees space and vision as freighted with meaning around lesbian subjectivity and disability. Shifting from the internal psychic tussle that the space of the interior represents, A Prayer reaches a cathartic end as Marsha leaves the building, compressing inside and outside into the same shot for the first time. Duckworth presents the viewer with a sense of resolution, the outside space marked as a metaphor for the self in the social world that Marsha now feels able to go back into. Finally escaping the enmeshing structures of Meshes of the Afternoon that have been redeployed throughout the film, Marsha leaves the interior learning to see and love herself for who she is post-diagnosis.

- Jacqui Duckworth, “Coming Out Twice,” in Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, eds., Jean Fraser and Tessa Boffin (London: Pandora, 1991), 155.

- Laura Guy, “Backwards Glances at Lesbian Photography,” Photoworks Annual, no. 27 (2017): 4.

- Alyce Mahon, “Profane Illumination: the 1938 Surrealist Exhibition,” in Surrealism and the Politics of Eros 1938–1968,(London: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 39–40.

- Lauren Rabinovitz, “Maya Deren and an American Avant-Garde Cinema,” in Points of Resistance: Women, Power & Politics in the New York Avant-garde Cinema, 1943–71 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 64–65.

- Kaja Silverman, “The Look,” The Threshold of the Visible World (New York, London: Routledge, 1996), 177–185.

- This image of the model is lifted from Duckworth’s earlier film, An Initiation to Marylin C, that dramatises lesbian revenge in the male dominated porn/film industry.

- Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Visual and Other Pleasures, (Basingstoke, Macmillan, 1989), 14–29.