By Elhum Shakerifar

Amel Moyersoen’s “afraid of losing the echoes” has been shown in London as part of the exhibition Collective Imaginings and in Brussels, and was selected for the System D Festival 2023, and MOOOV Festival 2024.

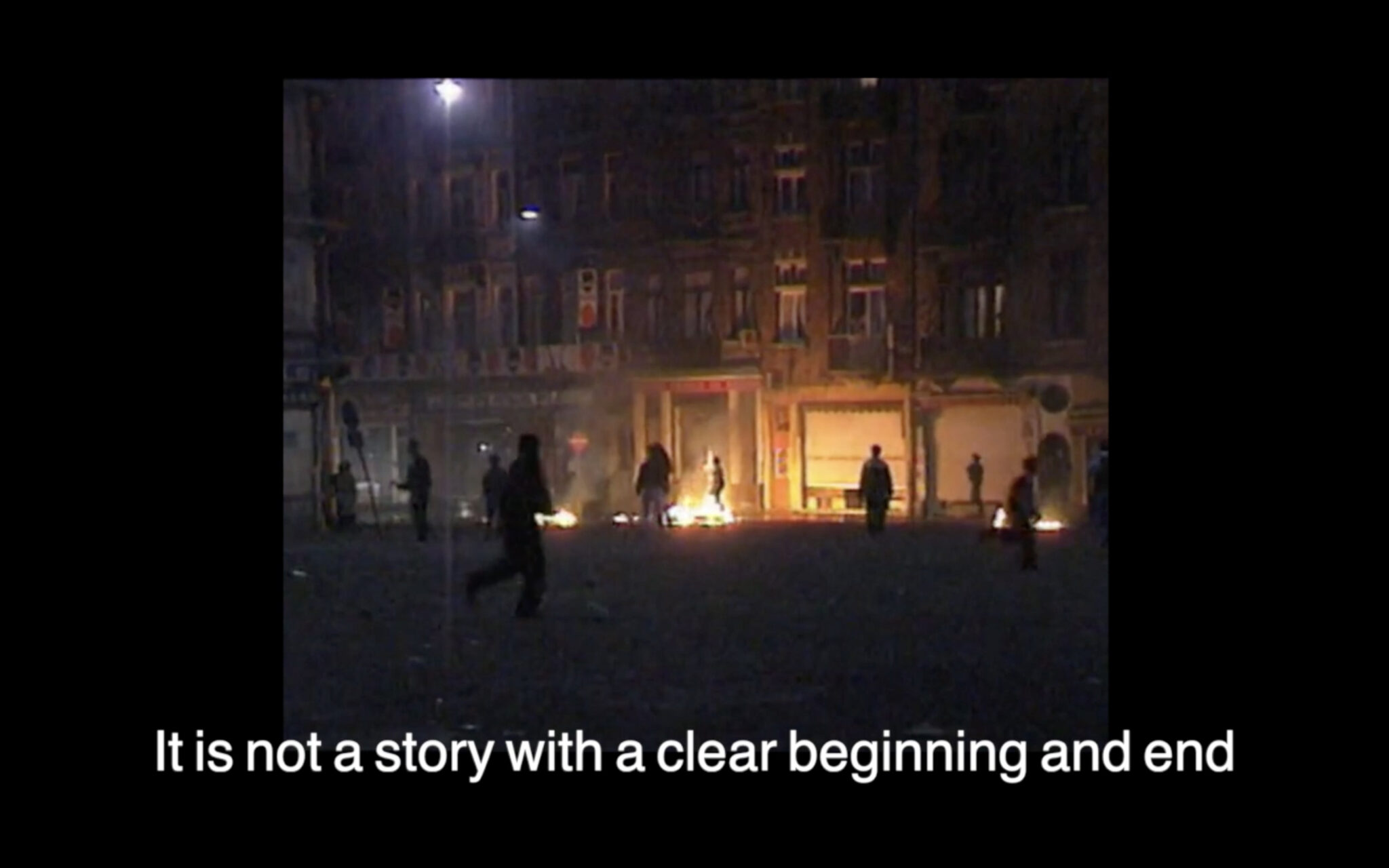

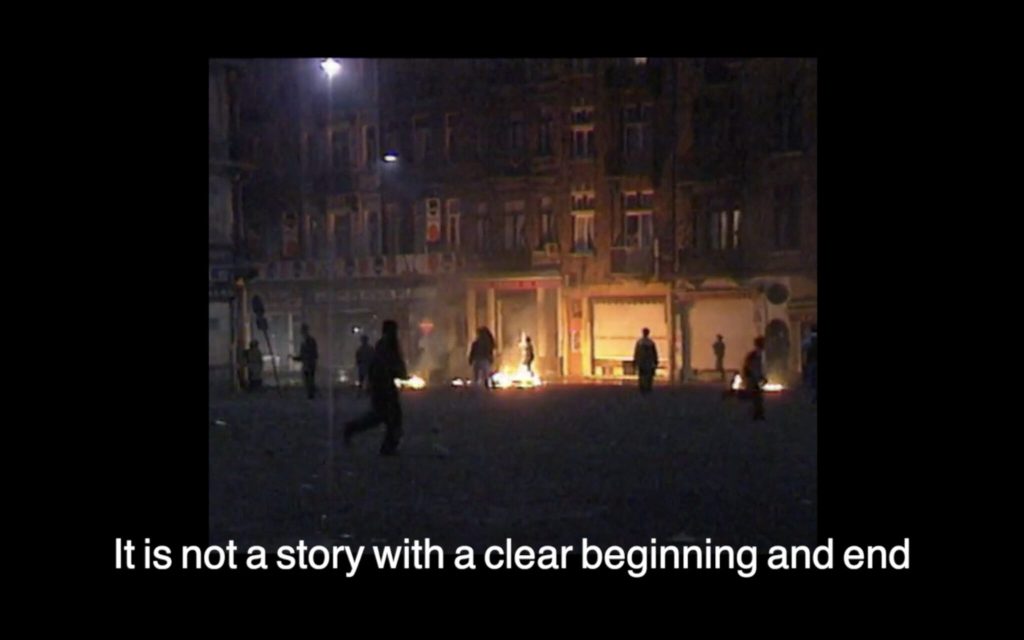

“afraid of losing the echoes” is an archive-based film, a memorial to those whose lives were lost needlessly at the hands of police violence in Brussels and a testament to those who continue to resist and denounce these crimes. Leaning into the grammars of poetry and protest, the film pulses with anger and possibility. An urgent, bold voice-over in French – poet Lisette Lombé – marches alongside images collaged from a range of sources. Jumps back and forth in time are hinted at through the grain of the image, the size of the frame, camera movement… but little else has changed, today’s protests echo yesterday’s.

To hear the French words while seeing the English subtitles evolve feels like being on a march or a protest where the signs through a crowd narrate the feelings that have caused people to gather. Where signs become the subtitles to the voices and chants that echo through the street. Meanwhile, the overlaying of word, image and voice presents almost as a challenge to piece together meaning – it forces you alert, simulates the state of permanent vigilance that a person of colour might experience in the public spaces that discriminate against them, possibly at the cost of their life. To bear witness, to record, to remember, to repeat are forms of resistance. “Pick up a pencil / Anything will do,” the voice over intones, recalling Diane di Prima’s evergreen words in her “Revolutionary Letter #2”

we are

endless as the sea, not separate, we die

a million times a day, we are born

a million times, each breath life and death:

get up. put on your shoes, get

started, someone will finish

Repetition, the title of the film suggests, is a survival tactic. It’s the sharing of information, the memorialisation of that which otherwise slips conveniently out of view. Recording, remembering. It is, as di Prima wrote, rejecting individualism as “a fog on our eyes,” as a credo taught “to instill fear, and inaction.” We do only live once. But we continue to live in one another – as Moyersoen poignantly concludes,

Who will forget?

Not me.

Not us.

Elhum Shakerifar: I’m struck in your film by the conjunction of voice, word and image – the reminder that a successful slogan is one that rhymes, just like the poems memorised in our childhoods. What does this mean for those of us who grow up protesting our right to live, to be, to be safe.

Amel Moyersoen: Poetry, recitation, repetition. In a world where our words, our demands, are rarely heard – or when they are, they are quickly consumed, and we are expected to constantly produce new material, new angles, to always be emerging, innovative, the next generation of something – there’s a power in refusing this demand for production. And instead choosing to repeat. Repeating the same demands, the same chants, the same stories. Insisting on continuity, connection, and the cyclical nature of our histories and movements.

But the repetition can also feel exhausting – the same demands, the same repression, the same acts of violence, almost identical, unfolding in the same streets, on the same squares, in the same police cells. We find ourselves standing again in response. I remember being on a square, mourning the death of Sourour Abouda, when her sister asked the crowd: “How many more times will we have to gather here, in front of this palais de justice?” Each death, each act of violence, is treated as an exception, each riot and act of resistance as if it’s the first. And yet, we know it’s all part of a much larger and longer history.

If we want our memories and histories to endure, if we want to build upon the work of previous generations of resistance, how do we pass on this knowledge without commodifying it, and without compromising its radical essence? Orality and repetition are ways of making memory, while at the same time allowing room for adaptation to new contexts and new times. Repetition reminds us that we are not alone, and we never have been. When we echo the movements of the past, we assert that those before us paved the way. By repeating, we honour them. We preserve memory. We chant into the future.

ES: Can you give me some context (some of my questions might be projection, so answer as feels relevant) – you were born in Brussels? Did you go to a French language school? What literature stayed with you from that time, and what literature did you reach for when you began to delve into other narratives that you weren’t being taught in school, in the wider society that surrounded you?

AM: I was born in Brussels and attended a Flemish-speaking school, my two other ‘home-languages’, Arabic and French, were strictly forbidden from classrooms, playgrounds or hallways. Home was thus the place where I was first politicised, as my parents transferred their causes and memories to me – housing battles in Brussels, the Algerian fight for independence, the plight of Palestine, and the challenges faced by friends fighting their way through the immigration system. But Brussels as well is a city that doesn’t hide, the tensions and negotiations are all there in the open: the battles for housing, for the right to gather in public spaces, for papers, for green spaces, and to end the cycle of police brutality are all overlapping and happening simultaneously. It’s also a city that happens to hold many international institutions and thus becomes a ground for global struggles equally. I became involved with ZINTV, a collective dedicated to documenting social movements in the city. We met weekly to learn the fundamentals of camera work and sound, and went out to cover protests for abortion rights, the sans-papiers movement, feminist gatherings, and countless vigils and town hall disruptions against the relentless brutality of police forces. Through this time, I became increasingly radicalised and politicised, gaining not only an understanding of the political dynamics of my city but also insight into the complex ethics and potential of documentation.

ES: Can you tell me more about the poem by Lisette Lombé that provides the voice over in the film, when did you first encounter it? How does it speak to your understanding of protest and community? Also is this your voice? Why was it important for you to speak (or not if it’s not you!)

AM: The poem by Lisette Lombé that forms the voiceover in “afraid of losing the echoes” holds a deeply personal resonance for me. I first encountered Lombé’s words during a feminist protest for healthcare rights and papers. It was a rainy day, and her voice pierced through the monotony of the march, cutting straight to the heart of everyone in the crowd. I was there with ZINTV, recording the protest, and I immediately felt the power in her words. Her flow – filled with anger, rage, but also with an unwavering sense of commitment and hope – captured the beauty in the midst of the struggle. I ended up making my first film based on that speech. The poem I used for “afraid of losing the echos” is one that actually originally speaks on writer’s block. After having gathered the archival footage as well as more recent footage on resistance against police brutality – thanks to my time at ZINTV – I found her voice to be a guiding thread through these archives of violence and resilience. I began to weave her words with the images, laying down the visuals to her rhythm. Having Lisette Lombé ‘s words awakened for me being at the protest and it only made sense for me that her voice would be the one to guide us through this history and resonate her rage, dedication and precision and art to the audience.

ES: I’m curious as to how your video work speaks to your work as an archivist at LUX. What does it mean to preserve but also to reinject art works back into the public sphere?

AM: Archiving, for me, is one possible step or part in the process of memory-making and transmission. It’s about honouring the act of documentation – acknowledging the deliberate choice someone made to capture a moment, a movement, and create their own interpretation or response to it, whether artistic, militant, or purely observational. By preserving these works, archiving can help ensure that these materials are reintroduced into the public sphere, where they can engage with new audiences, contexts, and times. However, it can be difficult to fully trust this mission to archives as institutions, as they exercise their power in regulating access to history, art, and preservation resources, limiting who can engage with these materials. This is why other forms of memory transmission – like the traditions of orality and repetition I mentioned earlier – are equally vital. They remain dynamic, alive, and integral to keeping histories in circulation and conversation with the present and future.