By Maria Paradinas

How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish has screened at a number of film festivals and at Barbican London, where Maria Paradinas hosted a ScreenTalk with filmmaker Mania Akbari. Subscribe to the Barbican’s ScreenTalk podcast for a recording of the discussion when it becomes available.

Mania Akbari’s films are available as follows: One. Two. One. is on Second Run DVD; A Moon for My Father is on dafilms; 6VideoArts and Lubion are on crypto-fiction.

*

When engaging with film archives and the uneven weight of audiovisual collections, one often comes up against uncomfortable images. Images that violate their subjects, and present their own position as objective and authoritative. Images that prescribe realities for the people who are captured, and with whom our interaction is mediated (and limited) by the director’s eye.

In these canonical archive settings, there is a proliferation of images for which the power structure between subject of the image and those who produced it is asymmetrical. What methods can be used to interrupt their way of seeing, and draw attention to a gaze which has naturalised itself?

Mania Akbari’s most recent work How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish (2022) reconstructs popular black and white pre-revolution Iranian genre films distinctive for their melodramatic and raucous style and tales of sex and violence. Traversing scenes from almost 70 archival filmfarsi works, Akbari enacts a series of interventions that turn the gaze on itself, remembering a positionality that had, as they put it, “forgotten its miserable existence”.

These archival documents are fiction films and therefore don’t declare themselves to represent reality. However, they do tell us about the fantasies and paranoias of the psyches that produced them. We are immersed into a dream of violence – women dragged and coerced to dance for male audiences, women abducted in their sleep, women drowned in the fields and hit in their homes. Fantasies of femicide, of avenging adultery, of the invasion of privacy, of rape and murder.

Of course, these are not particular to popular Iranian cinema and we would find similar scenes in the popular cinema of Western film traditions. In Akbari’s film these fantasies are shown to permeate time, location and media. A filmfarsi scene depicting a father dragging his daughter by the hair is edited alongside a plaque relief depicting the mythological tale of a Greek pursuing an Amazon, a handful of hair in his grip. Renaissance painter Titian’s 1511 Miracle of the Jealous Husband, shows a man holding a knife over his wife after she has been unjustly accused of adultery. This stands next to a scene of an actor depicting a jealous frenzy, repeatedly stabbing a woman who he suspects of adultery. By editing these scenes and artworks alongside each other in such succession, How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish emphasises their proliferation across culture. This highlights their artifice and ubiquity, making those who created these tropes and caricatures the subject of incisive critique.

Akbari argues that the fantasies shown in these films went on to construct reality. Their voiceover proclaims that their “body was born out of your distorted gaze”. If culture (especially popular culture) not only delineates the boundaries for which one is to be perceived, but also permitted to act and to express themselves, then as the sculptor creates bodies so too does the filmmaker.

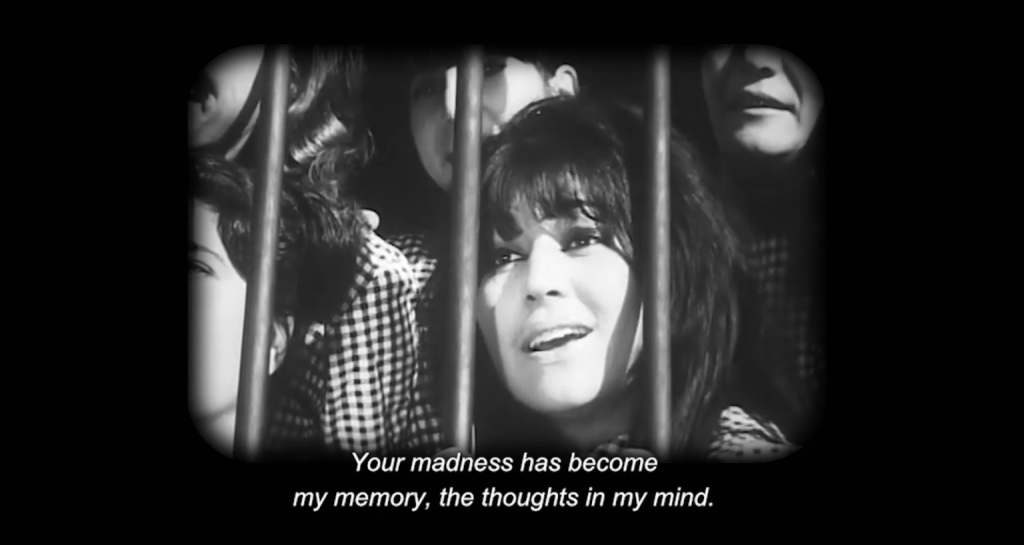

There is a strangely prophetic moment in which we witness a young woman singing to a man on the street below. “Your madness has become my memory, the thoughts in my mind. You are the master of arts […]”

Cinema archives often operate as sites where film histories are produced, and are called upon in the formation of collective memory. If we consider this to be an investigation into an archive of male fantasy and paranoia, where does fantasy end and reality begin? Is it possible to reach and encounter the actresses in the images, circumventing the gaze in which they are couched?

In How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish, and indeed elsewhere in Mania Akbari’s practice, they present their body as an archive: a storehouse of memory, joy and trauma. It is a site on which the gaze is inscribed, stored, and inherited. On the popular dancer and actress Jamileh they describe how: “We observed the curves of her body / which bridged past and present. We saw in that wondrous innocence / We preserved it in our bodies”.

As the past activates itself in the present via the body, the body is also an entry point into the past. The knife that is held in the hand of a filmfarsi actor is followed by a scene showing Mania receiving a tattoo of a floral motif across their chest, and the instrument of violence becomes a tool for creativity and self-articulation. The body expressed and presented on its own terms is the body in healing, and the body healed in the present is able to reach and repair the bodies shown in these archival films.

There is a line in How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish that has stuck with me since my first watching. Towards the end of the film Mania describes how “The scratchy, colourless and broken image of us is still our image”. There is a parallel drawn between the materiality of the archive that often exists in different states of decay or degradation, and the distorted image of the women held in it. It also calls to attention the fact that filmic material is vulnerable, needing to be handled with care. To me, this film feels as though Mania is gently cradling these images, sustaining an attentive, generous and loving interaction with the women presented in them.

The film closes with a scene showing the filmmaker and the actress Iante Roach dancing freely to the accompanying words: “We’ll reclaim our confiscated bodies from your masculine history”. The body that was previously confiscated and forced to dance for male audiences now dances on its own terms. Movement and decoration are avenues to reinhabiting the dispossessed body.

In How Dare You Have Such a Rubbish Wish reconstruction is presented as a practice of restoration and historiographic redress. By repositioning these filmfarsi fragments and weaving them together with the silver thread of Mania’s voiceover and own images, the original filmfarsi clips are compelled to speak to a different history – one of resistance.