By Annie Ring

It’s a Sin is currently available to watch for free on All4.

Annie’s new co-edited book Uncertain Archives: Critical Keywords for Big Data is out now, available as an ebook from Kobo (£30.69) and a paperback, with 10% off (£44.64), from Bookshop.org (UK). MIT Press have shared five chapters online free for readers (click on Reader Resources).

Soon after Russell T. Davies’ blockbusting series about the AIDS Crisis, It’s a Sin, dropped as a box set on Channel 4, the hashtag appeared everywhere in my social media feeds #BeMoreJill. It was referring to Lydia West’s depiction of the character Jill Baxter, a Black British woman who cares for the men she loves as they suffer from AIDS. Jill does so without apparent cost or resentment, which is extraordinary in a time when the Thatcher government was denying the epidemic, and the press, when it mentioned AIDS at all, did so in the most demonising terms. Now in 2021, the social media algorithm directed the injunction to #BeMoreJill to where it would most resonantly land: with me, a queer woman, who loves other queer people and makes my life in the community. The show’s creator himself tweeted the hashtag; meanwhile Channel 4 described Jill as ‘the friend everyone needs’, and online discussions affirmed that we all need a Jill in our lives. It was reported that the character is based on a real-life woman, a white British woman named Jill Nalder, who appears in the later episodes as Jill’s mother. The message coming from mainstream reviews of It’s a Sin was that I – and people with a psychometric social media profile like mine – should aspire to #BeMoreJill, to be more like this real woman who really cared in that way. As a code of conduct, it seemed clear what we are meant to do: like the real and fictional Jill, become a beacon of un-ambivalent availability, care and advocacy for our loved ones. Davies’ show robs Jill of ambivalence in a way that made me wonder how we can avoid our queer kinship relationships being complicit with neoliberal reductions of the state. Thinking through ambivalence, as I do below with reference to Roszika Parker’s feminist psychoanalysis, can help us by contrast to build more critical kinship for viral times.

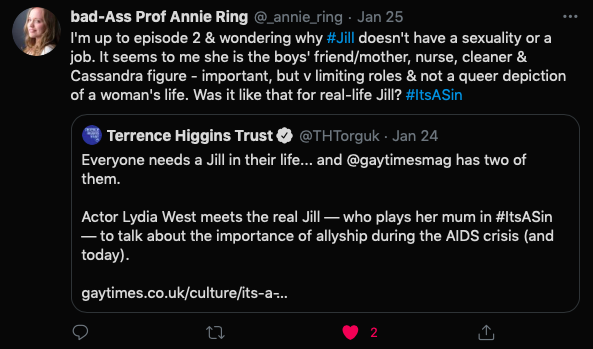

I was worried by Jill’s depiction in the show, and about the way in which the hashtag #BeMoreJill was circulating so uncritically. It made me think about hashtag archiving, the term coined by Black feminist scholar and founder of Hashtag Feminism (#F), Tara L. Conley, who writes in Uncertain Archives about how hashtags might be archived to capture dominant ethical and political narratives of our socially mediated age. After watching episode 2, I tweeted: ‘wondering why #Jill doesn’t have a sexuality or a job. It seems to me she is the boys’ friend/mother, nurse, cleaner & Cassandra figure – important, but v limiting roles & not a queer depiction of a woman’s life.’

I also spoke with my housemate about my worry at the oddly uncomplicated depiction of Jill. My question was: what does it cost us, the women and queers to whom the #BeMoreJill injunction is addressed, to be there for those we love in our alternative kinship structures in place of a caring society? Displaying no ambivalence, Jill is an icon of queer, non-biological maternity to the men around her. At the same time, Jill is the dream woman of the Thatcher era in which the series is set. And I am having nightmares.

Jill arrives into the show’s diegesis without much introduction. When protagonist Ritchie Tozer (played by Olly Alexander) arrives at university, she is right there, the good wing woman we see in the still above, bringing Ritchie and Ash (played by Nathaniel Curtis) together. Her first lines are telling: she says, ‘His name’s Ash’. Rather than giving her own name, Jill supplies Ritchie with the name of the man she is going to help him get together with. Later, Jill is there at Christmas, by Ritchie’s side to be a front to his worried family on the Isle of Wight. We learn little about Jill’s background, although we meet her supportive parents in later episodes. There is so much good in what Jill does. For me, alternative kinship instincts are at the core of the beauty of Jill’s work in the series. She is not related by blood or marriage to any of the boys she loves and cares for, and yet they are the centre of her life and she flexibly stretches to give them her concern, her time, and she exercises her political anger to try to protect them. Thus, along with the boys, the character of Jill queers kinship in a manner so refreshing to see in a series set in the 80s, an era of backlash against feminist and other social liberation movements of the 60s and 70s. It is also extremely refreshing to watch a depiction of queer, alternative kinship during the coronavirus lockdowns, when, from the beginning, the heteronormative un-word “household” has been the sole organising unit, around which UK policies in relation to Covid-19 have been thought, when care by the state had already been stripped back during years of neoliberalism and privatisation.

Aspiring for queer kinship leads me, in part, to admire Jill. I remember the love I felt for the gay men around me in my teenage years, the safety and sense of identity that loving them allowed me to feel as I discovered and began to live my own queer feelings. Jill cares for the boys gladly from the start. But what about her own life? In a queer-household montage, she sends the boys off to their job interviews and auditions. This sequence is charming and filled many of our locked-down, queer hearts with longing, as evidenced by the fact that a t-shirt emblazoned with a bold ‘La’ went very quickly on sale and, within twenty-four hours, had raised £20,000 for the Terrence Higgins Trust. That scene filled me with even more appreciation and joy in relation to the three friends I live with. We have kept each other going while working and resting in our separate rooms, and then coming together to sit through this long Covid winter around a bonfire in the back garden. It is something we know instinctively: we need to care for one another, as people, as a community. And so, when the boys need her to, Jill becomes a carer.

Central to my worry is that Jill is a woman of colour, to whom the series gives no sexuality, nor much of a working life, beyond a few short sequences on stage as an actress. The scenes of work in the theatre are lovely but frustrating in that they only show Jill onstage, and so do nothing to explore the labour done by artists backstage: the sweat and the tears that go into the illusion. In the earlier episodes of the series, Jill does not work while the boys do. Why does she not seek a job at first, while the boys are heading out, sent out by her loving ‘La’ to be interviewed for various casual jobs? We can assume that the boys do not pay Jill to clean, cook and wash up for them, so does she have family money? In Episode 2, Gloria, the first of the boys to fall sick, calls on Jill for domestic help, to keep him fed and to protect his privacy as he falls ill with the virus. Channel 4 samples this clip on its YouTube channel along with the caption: ‘After Gloria gets sick, Jill comes to the rescue; proving herself to be the friend everyone needs.’ Notice how in the kitchen sequence after Gloria’s visit, it is Jill who is washing up and so can destroy the pink cup and fake it as an accident.

By encouraging us all to #BeMoreJill, is the hashtag saying that we will not campaign for a taxation and care system that do what we all need, the Jills among us too? This is an intersectional feminist issue; it is in no man’s interest to acknowledge that women do not care “naturally”, to admit the cost of the labour we do. Historically, women of colour have especially been viewed as caring “naturally”, in a manner that hides the very high cost to them of their exploitation. What about the way in which HIV/AIDS affects women? Pippa Sterk notesthat the way women and trans* people were affected by AIDS is absent from the series: ‘you would think that the epidemic didn’t affect sex workers, drug users, trans people, people of colour or even anyone who isn’t conventionally attractive.’ Indeed, women and trans* people are not immune to the virus. In fact, recent studies from not long before the programme was made show that, globally, there are more women living with HIV than men.

The hashtag also highlights an issue relevant to anti-capitalist critique: it is not in capitalism’s interest to admit that care does not come naturally, freely, to those who do it. What does it mean to us to admit that it costs Jill not nothing, but perhaps everything, to do what she does? What becomes clear is the way in which the hashtag #BeMoreJill taps into the conflicts that necessarily arise between queer caring relationships and the politics of gender and capital.

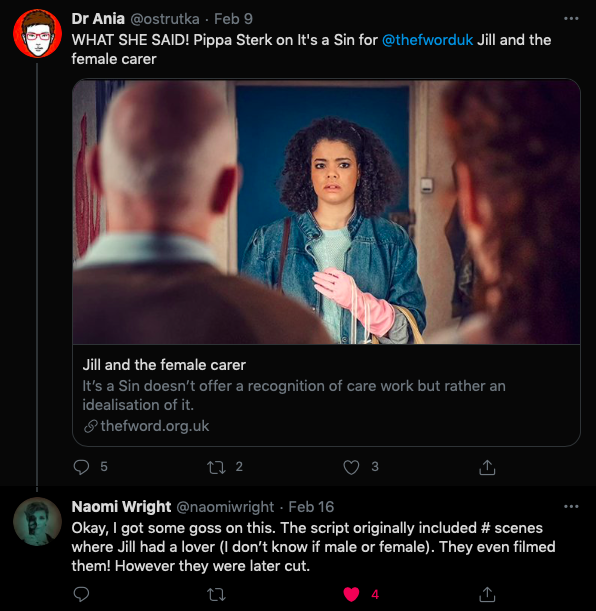

On the BBC’s Woman’s Hour, a show that tends to critique the roles foisted on women, albeit in a mainstream way, Emma Barnett asked Lydia West “are you a good person? Are you a person who cooks soup and brings it round?” If West does not do this, would she not be a good person, a good woman? Apparently, in Russell T Davies’s vision, Jill has nothing else to do but care. What bothers me most is that Jill carries out her work in loving the boys automatically, unambivalently. Moreover, I have not heard or read anybody but Pippa and myself worrying about this. Does Jill feel no ambivalence? Is it at all hard for her to care for the men? And if it is, what would ambivalence have looked like in the show? What I wanted for Jill was a few seconds’ more screen time in which her girlfriend is angry with her because she had to miss a date to care for one of the boys. Or in which she leaves a shift early and loses a job because she is needed at the call centre to give information and emotional comfort to callers seeking advice on their ill-health and fear of the virus. Admittedly, Davies had pitched a much longer series, and had to reduce its length in order to get the go-ahead and funding. This is no excuse, however, for leaving out any complexity from Jill’s character. Film producer Naomi Wright tweeted, in response to Pippa Sterk’s piece, that the script originally included scenes where Jill had a lover, which were even filmed but later cut.

It would only have taken a few seconds, or at most one minute of screen time, to create a vignette depicting some kind of difficulty or doubt about her caring role and the strain it places on the rest of her life to replace the government, the NHS, parents, a whole society for the boys.

I am arguing that the most problematic part of Jill’s caring role is her lack of ambivalence. Why does Jill need ambivalence? Ambivalence is a universal experience of nuance, difficulty, of love-and-hate all at once. It is a key word in psychoanalysis and was introduced by Sigmund Freud to describe how the life and death instincts co-exist, and he wrote that love and hate combine ‘to keep love ever vigilant and fresh’ (‘Thoughts for the Times on War and Death’ [PDF]), the instinct to protect becoming enlivened by the need to fend off more hostile impulses. Ambivalence is also at the heart of Roszika Parker’s feminist psychoanalysis of parenting in her books Torn In Two: Maternal Ambivalence and Mother Love/Mother Hate: The Power of Maternal Ambivalence (and also in Wendy Holloway and Brid Featherstone’s collection Mothering and Ambivalence), in which she argues that the coexistence of love and hate are not only unavoidable but in fact that they inspire and, further, improve a mother or primary carer’s awareness of what is going on between themselves and the child.

Parker found that ambivalence is felt by all primary carers of children; their love is always mixed with resentment, regret, and even hatred at times: think of the toddler who will not eat the lovingly-prepared food, or the teenager who persists in self-destructing, despite the decade or more’s worth of sacrifices made by a parent to ensure the child’s education is everything it could be. Do they inspire only love? No, there are more complex feelings in the mix. And those feelings need to be felt for the parent and the child not to become constricted in a frantic positivity. Think of the maniacally-smiling faces of Instagram parenting, seemingly denying anything other than positive emotion is present.Such forced positivity denies the existence of any more complex emotions, like resentment for the precious loved one – or indeed rage at the system that privatises and then leaves unpaid much of the care people need. Ritchie’s mother in the show, Valerie Tozer (Keeley Hawes), is so trapped in denial of complex emotions that she cannot see who Ritchie is and love him in a complex way, one that would challenge her to accept the emotional difficulty his sexuality presents her with. Memorably, when Ritchie phones home, Valerie does not ask him ‘how are you?’, but insistently asks him each time to tell her he is fine. There is no space for complexity or even basic difficulty here.

In Parker’s analysis, ambivalence needs to be felt because mothers or primary carers have to feel the full range of their feelings to be healthy, from the most positive to the most challenging, and to create a safe environment of feeling for the child – who can then feel their own full range of feelings, without fearing the more challenging parts of the bond with the parent and, later, bonds with others. More importantly, parental ambivalence must be felt in order to bring a thinking and a creativity to the relationship that remains absent if only sweetness, positivity and gladness are permitted to be felt amidst the challenging work that goes into raising a child. Ambivalence means that the parent is not merely merged with the child, but is able to separate from and so to think about the child and thus experience the bond as a relationship of self to other, instead of as a stifling (for both sides) merging of both into one single self. Parker writes about a client of hers, a mother who felt anger towards her children. Once she was able to acknowledge and feel the anger, it became a resource and led to a deeper sense of concern, in that it offered ‘a chance to consider the child, to renew the relationship, to free up the stuck quality of the bond’ (Torn in Two, 145). Fully feeling complex emotions, without horror or shame, crucially produces more thought in a caring relationship.

Jill does feel some anger in the show. In Episode 2, frustrated and concerned, she blurts out at the queer family’s dining table that the boys should be more cautious in their sex lives, and even stop having casual sex for a while as the virus is spreading in the gay community. Later, in the protest scene, Jill gives in to a brief moment of anger at the police, but she is soon ‘rescued’ from her anger and its likely violent consequences by Ritchie. In the image below, Ritchie jumps in heroically to stop a policeman who is beating Jill.

In Parker’s writing, the mother or carer’s ambivalence is described as necessary in order to produce concern, to lead to thinking about the bond, rather than dwelling in a perfect state of blissful merging. I want to add that ambivalence must also be felt and expressed in order to enable political thinking about care economies. If a parent or other carer is finding the work of caring challenging, the carer may feel resentment towards the vulnerable recipient of the care, which can, if acknowledged and felt without horrified denial, give rise to concern and to a thoughtful containing of feelings between carer and patient. However, a share of that resentment also belongs to a political critique of the lack of a state that cares. Anger is present, too, for a society that withholds care and timely prevention of the virus and its most devastating effects.

What does it cost Jill to care for the boys? We see her grieve in the show and we grieve along with her. But there is another cost to there being no state, no society after Thatcher’s work is done, to care for these men. At the end, Jill presumably risks defaulting on the mortgage on the flat she co-owns with Ritchie. We do not even see the complexity around that: the need to negotiate new terms for the debt, to recruit new co-investors, to work more hours or to move out and lose her home as well as the people she loves. Jill will need to be entrepreneurial to survive. And we know she can do this, having watched the show. Indeed, Jill is the entrepreneurial Thatcherite dream: at once a woman in the kitchen, waving off the men around her as they go out to work, and, at the same time, a canny home-owner who will survive despite the economic stripping-back of society going on around her. In these ways, Jill freely replaces the state that we surely hope would care for all of us, doing for the men what a more equitable and responsible society would do for us in states of viral infection, loneliness, amid the vulnerability of shame and of dying alone. This is the cost to Jill: she does not get to be her own, full, loving, and sometimes angry self. And if she breaks down and cannot care? There is no society around her to do it in her place. So: #BeMoreAmbivalentJill. It could bring about a change more powerful than relying on women, queers, and people of colour to labour for free in caring for those who are abandoned by government and society just when we need them most.