By Ania Ostrowska

Kangyu Garam is one of three Korean women filmmakers who are speaking as part of Sheffield Hallam’s free online conference South Korean Women’s Cinema, running Thurs 23 – Sat 25 Sept. Kangyu will be in conversation with Jeanie Finlay on Thurs 23, 3-4 pm – register here to receive a link to the programme and all events.

Following my lockdown-triggered horny review of Daughters of Fire, I am so happy to be back at Culture Club with a less frivolous piece. It’s about incarnations of the robust, although often critically snubbed, genre of feminist activist documentary, as seen in the work of one brilliant Korean documentarian. No masturbation scenes this time but high-octane feminist emotions guaranteed!

Kangyu Garam quit her job at the age of 31 and started making documentaries. Her instinct was right: she gained critical acclaim already for her 2011 debut My Father’s House, a story of her family and the property bubbles in South Korea (Best Korean Documentary Award at the 3rd DMZ International Documentary Film Festival) and the stream of awards has continued unabated since, including for Itaewon (2016). And yet, as she recalls in her latest film Us, Day by Day, which also won the Best Picture at the 2019 Seoul International Women’s Film Festival, Kangyu’s mother worried that her daughter wasn’t ‘spirited enough’ to be a filmmaker. To find this courage, Kangyu tells us she decided to document strong women’s voices in her films. I was introduced to her work during the London Korean Film Festival in 2017 and I immediately became a fan.

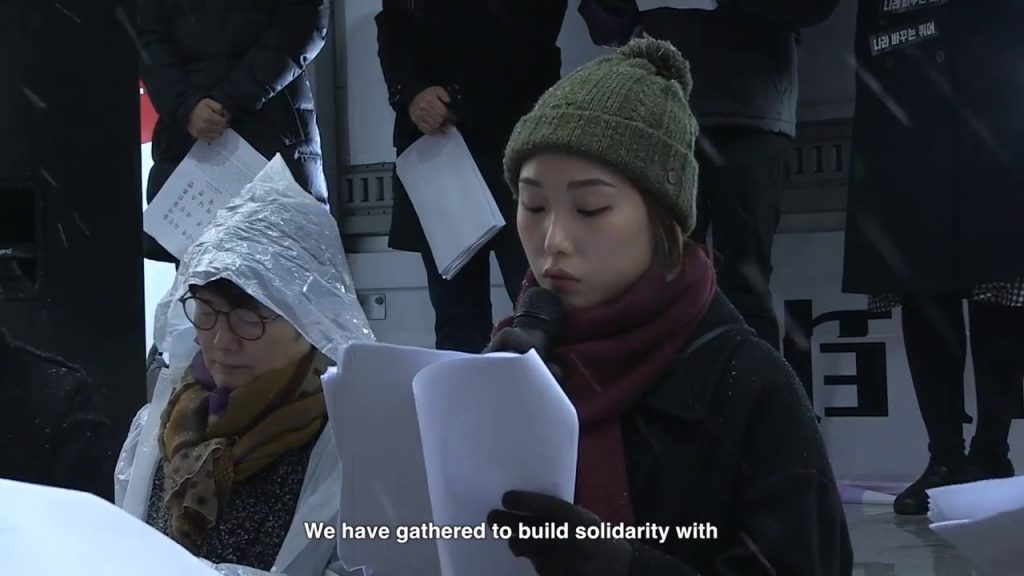

During the festival I chaired a panel discussion after the screening of her short doc Candle Wave Feminists (2017), arguably the pinnacle of documenting ‘strong women’ and their actions. The film, made as part of an omnibus project, consists of interviews with Korean feminist activists (from groups including Femidangdang, Network for Glocal Activism and Flaming Feminist Action) who created FemiZone, a safe space for women at mass protests that rocked Seoul in the autumn of 2016. People on the streets were demanding the resignation of corrupt woman president Park Geun-hye (subsequently impeached) and the conundrum for the feminist protesters was how to express their outrage about the actions of incompetent politician but divorce it from the toxic misogyny fuelling the ‘Candle Wave’ protests. On a practical level, they wanted to make sure that Korean women attending the protests would not be harassed nor abused by the men high on negative emotions towards the most powerful woman in the country. Politically engaged women who fight for mainstream (rather than women-specific) issues have long been ridiculed and abused, and this history includes such gems as Stokely Carmichael’s notorious flippant comment that “The only position for women in SNCC [Students’ Nonviolent Coordination Committee that he was leading] is prone”. Yuck.

Candle Wave Feminists is a feminist activist documentary at its best, with the battle cry “Proud feminists will save the nation” sounding loud and clear. While in that film the director remains behind the camera, Us, Day by Day begins on an autobiographical note, with the images from the author’s personal archive. Violence against women protesters, previously shown in news footage and mentioned in the interviews, here becomes the instance of personal abuse. Kangyu tells us in a voiceover that her feminist journey was accelerated by being harassed by a male activist during one of the protests she had attended in her youth. Joining feminist activist groups changed her life for good, and her testimony is a classic of the feminist consciousness-raising genre: “Seeing women vocally opposed to patriarchy gave me strength. I stopped blaming myself”. As this is a Korean documentary, there is also a sweet banner: “Feminism and me were meant to be”. Swoon. Now in her early forties, the director confesses she’s losing her sense of direction and meaning; to rectify it, she decides to visit five of her feminist friends from the full-on activist days in Unni Network, an online platform for young feminists popular some twenty years ago. She wants to see what they are up to now, hoping to get from them the strength not only as a documentary filmmaker but also as a feminist human being.

Her friends, who we know only by their first names or nicknames, have all followed different routes, with most of them being ‘part-time activists’ (the question of how to make a living while doing activist work, or how to find time for the latter while doing the former, keeps returning throughout the film). We meet Kira, a veterinarian who in 2001 in Busan joined feminist protests because of sexism in mainstream student organisations, and who now protests against breeding animals for bull fighting in her region; Jatury, a farmer and businesswoman on Jeju Island who in 1996 protested against the traditional stampede of male Korean Uni students against women from EWHA Women’s University; social entrepreneur Aura who is now running a women-only healthcare co-op but fondly remembers ‘dragging around a two-metre vagina sculpture during the protests’ back in the day; Omae, a full-time women rights warrior working at the Korean Sexual Violence Relief Center; and Flowing, indie musician and one time president of the student council committee for women.

They reflect on how their feminism and approaches to activism have evolved throughout the years as they were getting older, starting families, moving places. There are both continuity and breaks in their stories: for Kira, speaking against bull fighting is similar to protesting violence against women, as both groups are vulnerable and need protection; Jatury laughs as she remembers being suspicious of older activists when she was young while now she collaborates with older women to solve local problems.

I love independent Korean cinema especially for its tender and careful depictions of domesticity, especially food making and sharing. No wonder that the central scene of Us, Day by Day is an epic potluck dinner during which the film’s focus switches from individual biographies of activists to a broader context of contemporary Korean feminism. As Kangyu and her feminist friends, all in their forties, are sharing a tasty meal, they look back at the trajectory of the movement they spearheaded in the late 1990s and early 2000s and wonder about its future. They complain about the lack of existing mechanisms of mutual support, including intergenerational forms, within the movement and agree these should be created. The more self-care, networking and support among the activists, the more sustainable feminism will be. “There’s a lot we can learn from companies, like sustainability”, they muse, and agree that in a feminist trajectory there often comes a ‘shitty phase’ after initial involvement in one’s early twenties, and that one needs friends to survive it. Becoming feminist activists in different groups was life-changing for all of them but there is also a strong focus on feminism being ‘fun’ and feminists being potentially happier than the mainstream population as they grow older.

Ending her film Kangyu admits it did fulfill its therapeutic role: she had felt isolated and insecure but after seeing her friends ‘struggling day by day’ she is now committed to her own struggle as a feminist filmmaker. At a more universal level, the questions about activists’ self-care and its connection with the movements’ health and sustainability are timely and important. It may be obvious but comes across as very powerful when Omae shares what she does to be able to be there fully for her clients: “Day by day I take care of myself, reproduce energy, bathe, eat well, look up at the sky or at my cats. Those times are so important.”

The film’s structure really made me think about theorising identity as relational, one of the cornerstones of contemporary feminist philosophy. We need our friends and networks not only to stay safe at the protests, to share meals with or to have shoulders to cry on. It is through the stories that the others tell us about their lives, our lives, both of those entwined, that we fully understand who we are. That is where our strength comes from; sustainable social movements need that kind of strong individuals to flourish.

Further reading/ inspirations:

Belinda Smaill, (2012) ‘Cinema Against the Age: Feminism and Contemporary Documentary’, Screening the Past.

Cavarero, Adriana (2000) Relating Narratives: Storytelling andSelfhood, translated by Paul A. Kottman. Routledge.