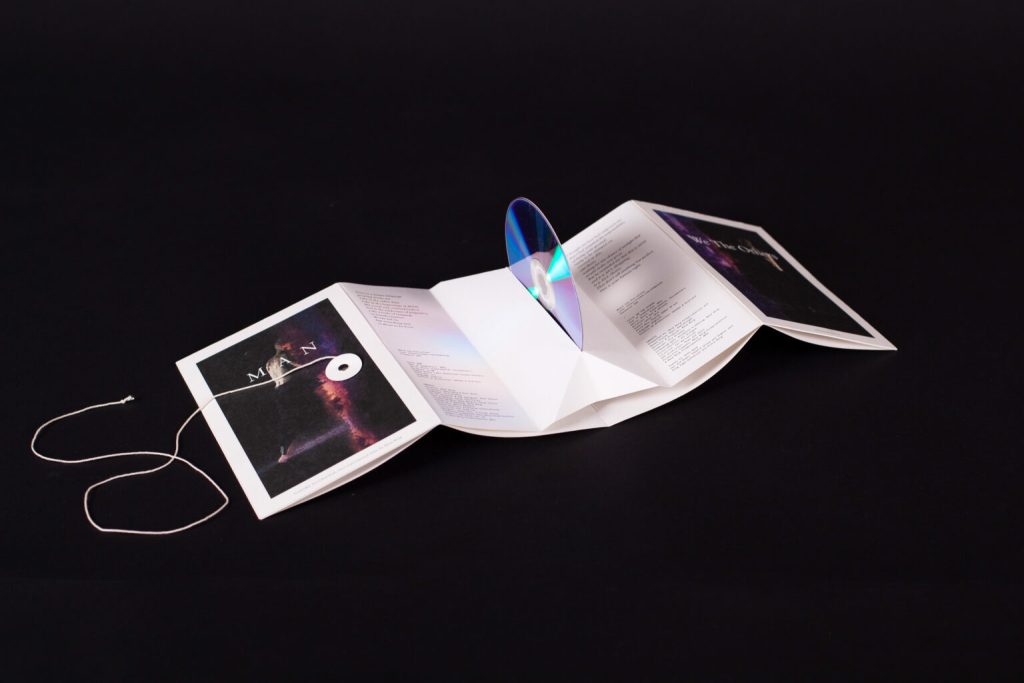

This essay originally appeared in the booklet for the DVD release of MAN (2016). Maja and So are in conversation with Melanie Iredale at Folkestone Documentary Festival, Sunday 23 October 2022, 6pm.

By So Mayer

…to talk of craft in connection with words is to bring together two incongruous ideas, which if they mate can only give birth to some monster fit for a glass case in a museum.

—Virginia Woolf, “Craftsmanship,” broadcast as part of BBC Radio series, “Words Fail Me.”

Virginia Woolf knows what she’s putting on show here: in the absence of a new language, she throws “old words in new orders” to startle us with what is in the glass case. Is it a marble statue of a goddess or a medical specimen? A holy relic or a rotten hulk? Both and all. What fascinates Woolf about language is its power to make us look, and look again.

Maja Borg’s films do exactly that, with all the languages that film has at its disposal. Princess, pregnant person, porn star; lover, worker, fighter: the varieties of visual existence usually assigned to women are reconfigured intimately through Borg’s voice, the thread of their presence and imagination that runs through all their films.

Woolf asks later in “Craftmanship,” “has any writer, who is not a typewriter, succeeded in being wholly impersonal?” The camera, even more than the typewriter, seems to make the impersonal (not to mention the apolitical) possible. Against the temptation of spectacle, Borg speaks: hesitantly, fluently, thoughtfully, poetically. And accentedly, deliberately marking one difference (nationality) that meshes with others. Gender, sexuality, class, ability become audible rather than – as much as – visible, pushing film form toward becoming a new language.

Words, Woolf continues, “like us to think, and they like us to feel, before we use them; but they also like us to pause; to become unconscious.” Whether shooting in black-and-white for “Ottica Zero” or on Super-8 for “We, the Others,” Borg creates pauses, a cinematic unconscious for both filmmaker and viewer. Shooting one image of themselves, posed like Vitruvian Man, every day throughout their pregnancy (“MAN”): an old word gives us pause; is given to us in a pause. When Tove Boström, one of the two the dancing princesses along with Joanne Faith Toner, playfully takes off her wig in close-up, breaking the fourth wall to engage our gaze (“We, the Others”): cinematic language shows us that, as Woolf decrees of verbal language, it is in its “nature to change.”

Future My Love, Borg’s feature, destabilised both past and future, excavating memories of futures once imagined and not realised – setting even what seems settled, the past, free to change. Working with time and the body in “MAN,” they alter what has been offered, even by some feminisms, as unalterable: the enmeshing of pregnancy and femininity, of body and nature. Like their witty and heartfelt intervention in “We, the Others,” into both the traditional fairytale of the princess, and the medical fairytales of perfectibility that we now whisper to ourselves, their crafted and crafty take on pregnancy, gender and desire in “MAN” is, in the best sense, monstrous: altered, emergent, demanding our attention.

As Donna Haraway writes in the introduction to Simians, Cyborgs and Women, “these boundary creatures are, literally, monsters, a word that shares more than its root with the word, to demonstrate. Monsters signify.” Borg is a significant filmmaker because they are not afraid to make monsters, to bring together two incongruous ideas and show them, boldly. “Demonstrate,” strangely, applies both to teaching in the science lab or medical school, and to the possibility of taking to the streets. Both rigorous and anarchic, Borg’s films fit – like a sleeping princess – in a glass case, only to shatter it with a kiss.