By Frances Morgan

The Assistant is available to rent or buy from a number of online platforms: Birds Eye View have handily collated them. We recommend Curzon Home Cinema (£3.99 to rent).

Because you watched…

During the spring and summer of 2020 I wanted to be told bad stories. A bad story is not just a story about something bad. A bad story is more a way of telling. It uncovers the bad, layer by layer, or it starts with the bad and piles on more. Its format has the same momentum as the events it describes, which might be the building and toppling of a tech grifter’s empire, or the discovery of new clues to a cold-case murder, or the fall of a dictator, or just that what you thought you knew about history was wrong. A bad story keeps moving, keeps building or peeling back the layers. Maybe a bad story is not even a story at all but a rhythm. In lockdown, I locked in to the rhythm. Algorithmic recommendations kept it running. Because you watched, said Netflix, reminding me that I had asked for this. A bad story is an engine. You could keep it going for months if you kept refuelling it. I kept it going for months.

Sometimes I would tell myself that this was not a true crime thing, I’m not into true crime, and then I would decide that everything felt like true crime nowadays so I might as well cue up another episode. Somewhere between these two statements lay an idea about narrative structures and violence that I might get to later, once I had finished work for the day, once I had finished the podcast about MLM scams. I never got to it.

When I watched Kitty Green’s film, The Assistant, it’s possible that I thought it might be a bad story too. I knew that it was inspired by the exposure of Harvey Weinstein’s abuse of women in the film industry, which had been covered up and enabled over many years. Weinstein is a very bad story, one of the worst, but The Assistant does not tell it like one. Its timing is off. I had started to watch films and TV with my attention partially elsewhere, split between screens: the visual grammar of bad stories, as predictable as their rhythm, made this easy. But I found that I couldn’t have The Assistant on in the background, because it is all about the background.

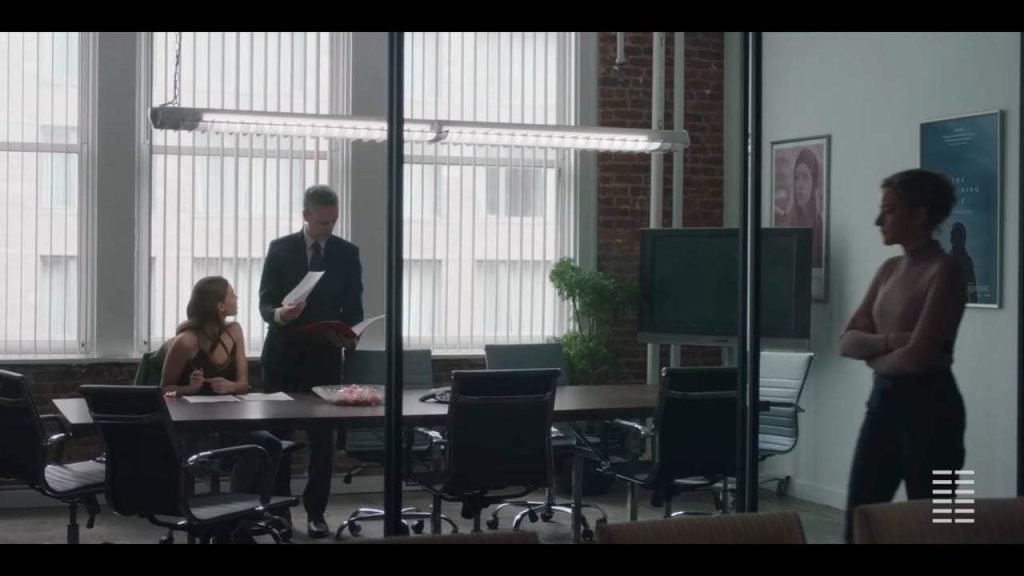

The Assistant shows a day in the life of Jane, played by Julia Garner, the new assistant to a film producer. The film is set in a cold New York whose daylight hours Jane barely sees because she gets up before dawn and leaves the office after dark and lunch is ordered in. In a moment of crisis she sneaks a cigarette break and the sight of the blankly grey city sky is almost shocking, as if you had forgotten that there was an outside.

The crisis is not the revelation that the producer is a sexual predator and a bully, because Jane knows this already. That morning she has already cleaned her boss’s couch, tidied his office and returned a discarded earring to a young woman, quietly handing it over outside the lifts. The crisis is that she is no longer able to abstract the producer’s behaviour into tasks to be done and problems to be solved. The couch, the earring, the discarded viagra vials and needles that have to be bagged up and disposed of, the angry phone calls and emails – all of these can all be handled and cleared away somehow. But today another young woman has arrived at the office, claiming to be a new assistant, and there is something about her, about her presence in the office, that can’t be easily tidied away. Jane watches as a man in a suit thrusts a pile of forms at the young woman and briskly asks her to sign, “there, there, and there.” Her next task is to take this young woman in a cab to an upmarket hotel. We see them sitting far apart from each other in the back seat of the car, guardedly friendly, trying to figure out what are the safe questions to ask and the safe responses to give.

Even before the young woman tells Jane that she met the producer while working as a waitress, you can see subtle class differences articulated in their clothes. Jane wears a dusky pink high-necked top, heavy black shoes and pin-striped trousers cut high on the waist and ankle – the outfit of someone who hopes to be wearing expensive, understated but interesting clothes in ten years, by which time she will have upgraded her parka to a good coat and lost the too-long, studenty scarf. The other young woman has on skinny jeans and sneakers and a bright green puffer jacket; her hair is bouncy and loose (Jane’s is tightly pulled back). When she comes back into the office later, she carries a little floral-print rucksack, like something a young teenage girl would have. They don’t exactly come from different worlds; they probably started out in similar ones, but they are now, at this point, in the world differently.

When Jane goes to her HR manager – played by Matthew Macfadyen as both expansive and ruthless – to voice her concerns about the producer and the new assistant, he detects these differences and works them like an expert. He suggests that Jane is a snob, Jane is jealous of the new assistant who hasn’t had to jump through the hoops of prestigious university degree and internships that she has had to. When Jane refers to her as “the girl”, he corrects her – “she’s a young woman” – so Jane is a bad feminist, too. Jane has got what it takes. Jane is wasting a valuable opportunity. Jane hasn’t actually seen anything bad happen. There’s nothing that Jane can say to this because it is all a bit true.

Watching this scene for a second time, I think of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, where the creepy men in the boardroom and on the film set force Justin Theroux’s Adam, a young hot-shot director, to choose a certain actress for the lead in his film. When he sees her audition, he is to utter the words, “This is the girl”. Those are the rules: this is the girl. It doesn’t matter who the girl is. “What can we do?” asks Jane in The Assistant. “About what?” the manager says. “About the girl”, Jane says, as if putting enough emphasis on the word “girl” will make something happen. The weight and ephemerality of this word, “girl”, of being a girl, recurs throughout Lynch’s films, where girls are mystical and expendable. It’s like they’re always fighting to be more than just an idea, more than just “the girl” who gets chosen or doesn’t; the girl who gets seen or gets away. Their vulnerability has, for Lynch, an almost occult potential. In this scene in The Assistant, in that very brief moment, the way in which emotion – girl-emotion, her own girl status – breaks through into Julia Garner’s voice and is met with the bureaucratic impassivity of Macfadyen’s, I hear something like one of Lynch’s disconnects between registers and worlds, into which that potential might emerge. These disconnects are sometimes terrifying and sometimes absurd; sometimes they just go nowhere but they still stay with you; you think, what just happened? Who was I in that moment?

The HR manager says, “I could file a complaint for you, if that’s what you want, but I think you know how it would come off.” So Jane leaves and the girl disappears from the conversation and from the record and from Jane’s voice.

A bad story does not allow for moments of disconnect like this. In a bad story connections and their breaking should be clear, so that when it all come crashing down at the end we know how we got there. In a bad story we would see the producer and the girl at the hotel. We would see Jane find an ally in one of the cynical trainee bullies she works alongside. One of the exhausted middle-tier managers, sick of having to tell important visitors that the producer is “in a personal” this afternoon, might exchange some words of empathy with Jane in the lift. We would see more of the faces behind the many voices that are mediated through Jane’s office phone and cellphone: it’s notable that The Assistant’s voice-only cast list is almost as long as its regular one and, in a kind of tonal reversal similar to the film’s forefronting of small, mundane actions over explicatory drama, the voice characters have the most to say. Their words spill into the office, Jane has to mop them up. “I’ll fix it,” she tells a panicking housekeeper.

Small actions are The Assistant’s action. They’re mostly actions that will have to be done again and again, like cleaning, calling, copying, carrying; sorting things out. Sometimes they are shot from above like a YouTube tutorial where you see busy hands doing something fast. Sometimes they make you jump, although all Jane is doing is slitting open a box of mineral water bottles and mixing up a Huel in the blender for her boss. When these actions become the action they are amplified sonically and symbolically. The irruptions of sharp-edged sound remind you of the potential for splatter and accident in a job that requires you to be composed and invisible, fixing intangible things, a calm voice on the phone, simultaneously disembodied and attentive to others’ bodily wants and comfort. Moving between these actions without making a mess somewhere is tiring. When are you supposed to eat? Here’s Jane trying to have a bowl of Cheerios, Jane taking a bite out of a leftover pastry from the meeting room, Jane trying to have a sandwich, Jane trying to have a ready meal, Jane trying to eat a muffin on the way home while calling her parents. Every time she tries to put something in her mouth, she has to stop and do something else.

Watching The Assistant it occurs to me that I have never seen a film before that shows what it’s like to eat at work, and that maybe this is the story that it wants to tell, or tells in spite of itself: the story of how work does not give you sustenance, and does not allow you to sustain others. How can you articulate abuse and injustice when you don’t have time to put food in your mouth? This is a story without a neat rhythm; instead it has a hungry and insidious and complex one, a kind of anxious guilty stumble without resolution. This rhythm is muffled and hard to break. What would happen if we broke it, if we took a break?

When I was in my mid-twenties I worked briefly as an editorial assistant for a large academic publisher. I worked with young women who were a bit like Jane, low-level anxious, wearing pink tops – although because it was the early 2000s these would have been tightly fitted cardigans; think Lorelai Gilmore. We were all assistants but with slightly different titles, like a set of action figures from the same fictional universe. We would process photo permissions, get a croissant for Professor X, liaise with the proofreader, liaise with the designers, update a publishing schedule, call the repro house, check proofs, make sure Professor Y had a fridge full of Diet Coke, set up the meeting room, book endless Addison Lee cabs, collate a list of corrections, book a conference call with the New York office. There was one man on the team when I started but he got a better job somewhere else and soon left.

By this point in my working life, I knew how to do service jobs and I knew how to do things with text and layouts very fast, because I’d been a waitress and a desk editor. Being an assistant requires you to be both at the same time. I found that my ability to hyperfocus on words and patterns, which made me good at editing, was useless, was in fact a liability, when I had to switch modes and carry a tray of those little triangular sandwiches that taste of recycled air down the corridor while trying to make polite conversation with a client. A lot of the time I felt like a giant, like an animal in clothes. The only way I could see out of it was to do more work, work that did not make me feel deranged, so I wrote record reviews in my lunchbreaks and went straight from the office to band practice and soundchecks several nights a week. I worked for friends, not bosses, off the clock, under the table, for myself, for art, for music, for love, as they say. Then one day we all got laid off. I freelanced, then I edited a magazine for five years. And then I had no idea how not to work all the time. I learned to fetishise creative work, and inevitably to work the feeling of work into my work: I look back at some of my writing from this time and it often sounds flung, rattling; it has a plate-spinning, tap-dancing quality. I was really into the word ‘frayed’.

I could say that my assistant job was when I learned to overwork, but it’s only one origin story among a number of possible ones – a small one nested within a much bigger one. I could also say that I don’t overwork anymore, that I aged out of that addiction the way I aged out of cigarette breaks and writing all-nighters. But not everyone gets to age out of precarity. I watched The Assistant one evening in July after pulling an 11-hour day doing the two freelance jobs I had held onto through the first wave of Covid-19 that saw numerous people I know lose some or all of their income. I knew that I was lucky to be working, but I also knew that if I stopped, I’d be screwed, so I didn’t stop. It had been a long day, but as I lay on the sofa with my laptop balanced on my stomach, looking for something bad to sort of watch, I felt peaceful. For now, I didn’t care about the lack of job security for casual teaching staff – something that we had gone on strike about earlier in the year – or the decimation of the musical communities I love, or anything much. Maybe I would eat something in a bit. Was there anything to eat? I wasn’t sure, didn’t really care. As I had often done in the months leading up to this particular day, I had worked until I reached a state in which all I wanted was the implacable cadence of a bad story as it recounts and then counters, recounts and then counters, so that the abuse, the lies, the violence are balanced and harmonised with the truth, the justice, the ending. All the moving parts, moving together.

In The Assistant, Jane does not care – she cannot care. She thinks – I think – overworking is caring but I know – she knows? – it’s the opposite. She has no idea. Her attempt to care (“What can we do about the girl?”) is so tellingly unpracticed. It flares up and burns for a second and then it’s gone. Compare this to the complicated but constant presence of care and caring in another subversion of the bad story that was released in 2020, Michaela Coel’s TV series I May Destroy You, which ends not with one of the revenge or redemption plot lines that Coel floats in the final episode, but with a group of friends sitting together. They have struggled to know best how to care for one another in the aftermath of Arabella’s sexual assault, but they keep caring and fucking up and still caring, and this is the rhythm of the story, not the assault. You know that it will keep itself going after the final credits.

In music, a cadence is a device that tells you a musical phrase is coming to an end. Some sound more conclusive than others but we understand them to mean that things are finishing up and we can rest, even if the ending sounds like a question (the bad story often favours an imperfect cadence, leaving space for reflection, a frisson of fear, or another series, but you know it’s over… for now). Both I May Destroy You and The Assistant counter the cadence of the bad story in different ways, disallowing the standard ending to remind us that the working day does not end, trauma does not end – but also that care does not have to end, either.

Watching The Assistant did not wholly cure my addiction to bad stories, any more than this year’s reconfiguring of the workplace has cured my tendency for presenteeism. Some nights I still want someone with a peppy voice and decent politics to tell me about terrible things. But something happened around the time that I watched Kitty Green’s muted, disquieting film. Some air got into the engine and it faltered, briefly. It has not worked quite as well since then. I’m not sure that it will again, or that it should. The space opened up by that malfunction was a space to remember and reassess. I found that I could speak up about something I was concerned about, something that was harming others. I changed jobs. I grew three aubergines in a pot and grilled them outdoors and ate them with too much paprika and oil and salt. My friends took the leftovers to Epping Forest and ate them while coming down off mushrooms. The other day my partner’s brother, who is addicted to politics podcasts, recommended a series about the Iraq War, and I haven’t listened to it yet, maybe I won’t. Making small changes, means to not-ends; not fixes or one-neat-tricks, more like practices of modding and tinkering, which are both personal and idiosyncratic, and shared and adapted. Making ready for another year of this, which cannot be another year of this.