By So Mayer

The Gold Diggers (Sally Potter, 1983) screens twice with intros by CDF’s So Mayer, as part of Cinema Rediscovered 2025, 23-27 July in and around Bristol.

Saturday 26 July, 11 am, Watershed Bristol, with The London Story (Sally Potter, 1986).

Sunday 27 July, 1 pm, Curzon Cinema & Arts Clevedon (with free tour of the cinema at 12!).

Serious and Sparkling: Sally Potter’s cinephile dream, The Gold Diggers

The Gold Diggers is a unicorn: the first British feature film written, directed, produced, edited, designed, shot, choreographed and led by women. An exhilarating, ambitious and often-obscured high watermark for intelligent political filmmaking, it definitely went ‘against the grain’ of British cinema in the 1980s. Funded by the BFI Production Board, it reverberates with the energies of the 1970s emergence of an exhilarating experimental British cinema, supported by festivals such as Edinburgh and the First Independent Film Festival, which took place at Arnolfini in Bristol in 1975. Sally Potter’s first feature Thriller (1979) debuted at Edinburgh ’79, as part of the famous Women and Film Week, leading to a sold-out season at the Ritzy in Brixton as well as a US college tour.

Teaming up with members of the Thriller team and bringing Julie Christie on board, Potter pitched a full-length feminist feature to the BFI, and secured the largest budget then ever given to a British woman director, £1million, which enabled her to shoot in black-and-white on 35mm, in Iceland. Between pre-production and release fell the blow of Chariots of Fire (Hugh Hudson, 1981), which inspired the cry of ‘The British are coming!’ and a drive for the well-made historical film. Surprisingly enough, few queer Marxist feminist anti-imperialist detective musicals shot in black-and-white followed The Gold Diggers to the screen.

That may sound daunting as well as exhilarating – but The Gold Diggers shows that films can be all that and brilliant homage to the whole history of cinema. In fact, they can be all that because of the great riches of the history of cinema. The film is a cinephile’s dream, a fact made clear by the season that Sally Potter programmed for the National Film Theatre to launch the film in May 1984. It ran to twenty-three separate programmes, including two of the clearest influences on its play-within-a-film about a poor miner’s daughter, D.W. Griffith’s Way Down East (1920) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) – drawing attention to parallels and connections between the extractive Gold Rush of westward expansion, and the ‘gold rush’ of Hollywood’s establishment in California.

Hollywood film fans were well served by Potter’s deep cinephilia, with a cavalcade of musicals, starting – of course – with The Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy, 1933), and running through Dance, Girl, Dance (Dorothy Arzner, 1940), Hellzapoppin (H.C. Potter, 1941), and Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen, 1952). These were juxtaposed with an alternative tradition of song and dance on screen in the Brechtian Kuhle Wampe (Who Owns the World?, Slatan Dudow, 1932), baroque The Red Shoes (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1948), experimental Lives of the Performers (Yvonne Rainer, 1972), and avant-garde classic Study in Choreography for Camera (Maya Deren, 1945).

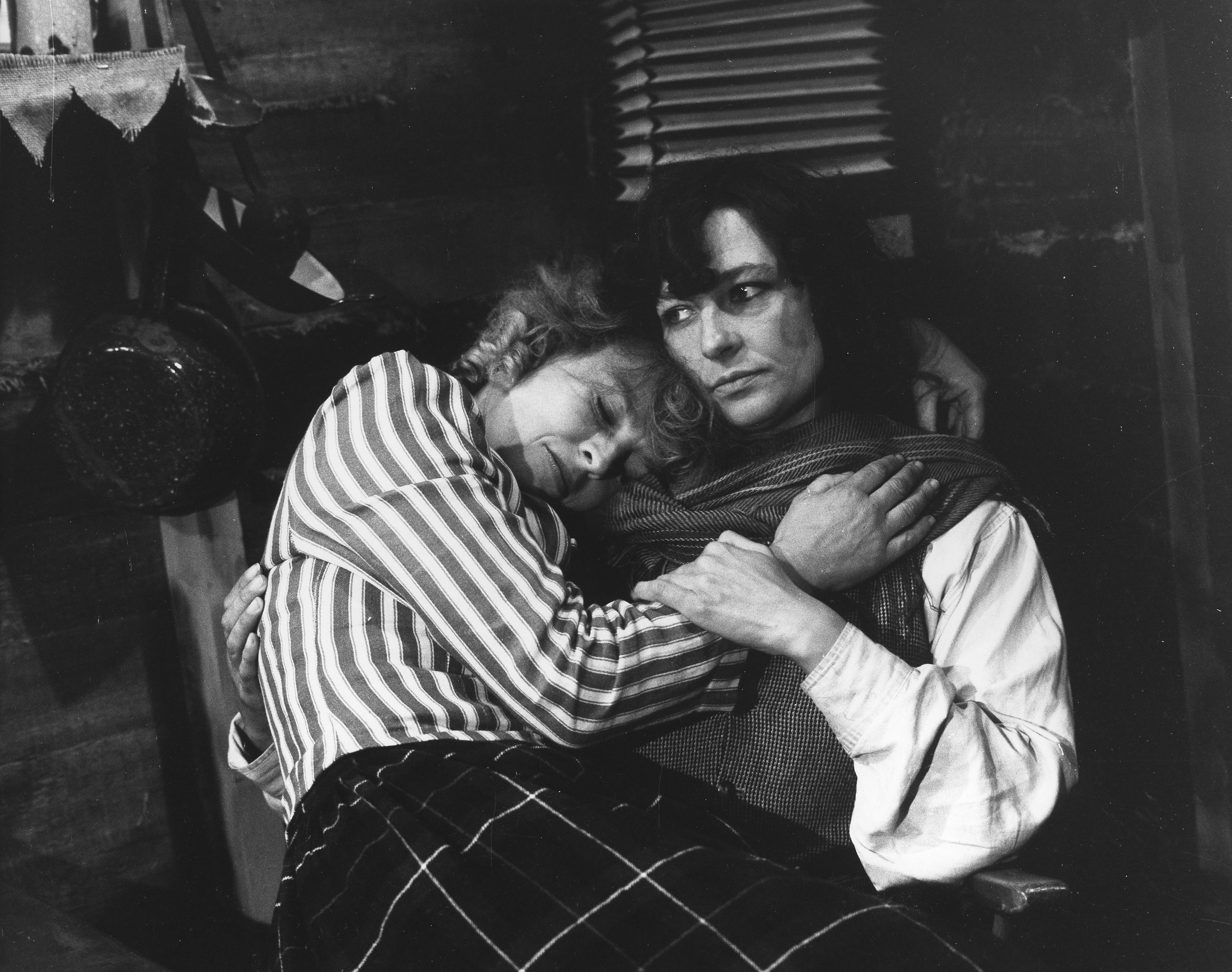

The Gold Diggers is not just a musical, but a thriller of doubles and mirroring informed by films programmed by Potter such as The Lady Vanishes (Alfred Hitchcock, 1938), Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966) and Julia (Fred Zinneman, 1977). Everyday detective Celeste (Colette Laffont) tries to solve the problem of money: not just how to have it, but what it is, and how that connects to gold, banks and the protection of white women – in the film’s case, Ruby, played by Julie Christie, the belle of the ball who grieves for the loss of her mother. If that sounds familiar, then Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965) was right there in the season, alongside the iconic Darling (John Schlesinger, 1965), in which Christie also plays a pin-up who tries to get free.

Potter delved deep into the relationship of the female icon and the cinema screen, programming Queen Christina (Robert Mamoulian, 1933), Madame de… (The Earrings of Madame de…, Max Ophüls, 1953), Lola Montès (Max Ophüls, 1955) and Une femme est une femme (A Woman is a Woman, Jean-Luc Godard, 1961), as well as avant-garde critiques La Souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet, Germaine Dulac, 1923) and Joyce Wieland’s Rat Life and Diet in North America (1968). Offering an extended arthouse feast, Potter included Alexander Nevsky (Sergei Eisenstein, 1938), with a stirring score by Sergei Prokofiev that gives the film its ‘symphonic structure’; the picaresque Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie (The Saragossa Manuscript, Wojciech Has, 1965), with its tale-within-a-tale; and hybrid docufiction, centred around opera, The Power of Emotion (Alexander Kluge, 1983), positioning The Gold Diggers as Hollywood studio–meets European arthouse–meets feminist avant-garde – WITH SONGS!

Shot in lustrous black-and-white in Iceland – where the ground is light and the sky dark – by Babette Mangolte, Chantal Akerman’s regular cinematographer, The Gold Diggers also spoke directly to contemporaneous feminist audiences and discussions. Its score by Lindsay Cooper sold out on its release by Deutsche Grammophon. Cooper, who had also scored Edinburgh ‘79’s most noted feminist experimental documentary The Song of the Shirt (Sue Clayton and Jonathan Curling, 1979), was a long-term musical collaborator with Potter, performing live together around Europe including their leftist historical song cycle Oh, Moscow!.

Like Rainer’s Lives of the Performers, Potter’s film also showcases England’s version of Judson Dance, the contemporary movement in which Rainer played a role as choreographer and performer. Potter puts her collaborators and peers from The Place, the UK’s first and premier contemporary dance school and stage, on screen: Siobhan Davies and Maedee Dupres are part of the dreamlike dance in the bar, dressed up like Brassaï butches, while, in one of the film’s funniest scenes, Jacky Lansley waylays Ruby to get her advice on how to do lifts now that she’s gone solo.

The Gold Diggers, like gold itself, is both serious and sparkling, gorgeous and weighty. It glitters with an off-kilter sense of humour and the ravishing confidence and sense of community that came from working with an all-female crew, the first time for any British film. There were no unionised women sparks, so Potter found electricians willing to learn: look out for the blowtorch-wielding welder who appears on screen at the very end, a tribute to her crew behind the camera, and to God herself sparking (re)creation, as Celeste and Ruby swim naked in the deep.

Are you ready to dive in?

*

This piece was commissioned by Watershed as part of Cinema Rediscovered Festival’s Other Ways of Seeing initiative with support from BFI Awarding Funds from National Lottery.