By Pamela Hutchinson

The Watermelon Woman is available to stream for subscribers of the BFI Player and the Criterion Channel, and via its UK distributor’s Peccadillo Player.

The Fae Richards Photo Archive is published by Artspace Books(US), and can be ordered from UK booksellers.

I write about the cinema of the past, but for progressive people who want to hear stories that defy oppression and conformity. These are people just like me who love to hear about the trail-blazers, the courageous pioneers who trod where others dared not. We show our opposition to the prejudices of our own age by celebrating those who faced down much worse in the past. In this club we also enjoy mainstream movies with subversive messages, and coded characters. It’s a way of finding comfort while acknowledging the fact of oppression, which strikes me as not very progressive at all. In many ways it’s a trap.

I write and read stories of women who broke into male-dominated industries, of people of colour who fought for their rights, of gay or gender-non-conforming people who felt free in their own skin. The flipside of this, which covers all the lives squandered, hopes thwarted, the hearts broken, goes largely unrepeated. History is written by the victors. Film history is written by the people whose credits remained on the film, the people who were interviewed by the fan magazines, and sought out by academics in their dotage to narrate their careers into a tape recorder.

So I love Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman for enacting how hard it can be to sift through history to find those trailblazers who actually left little trace behind them. And also, how history doesn’t always reward us with heroism. Unlike other recent Hollywood revisionist fantasies, it refuses to get carried away with making over the past as a haven for queer Black life. First, there’s a lot here on the stumbling blocks in triplicate encountered when researching figures from film history who are female, Black and gay. Second, the story it uncovers doesn’t fit any Hollywood templates of rags to riches, or obscurity to stardom.

Dunye told the LA Times recently about her search for a subject:

Tons of people were in Black cinema… There had to be a gay person in there. But it’s written out of that text and all the books. Flip to [the history of] lesbian and gay cinema, what you do get is women, but not women of colour. Somebody existed [during those times], just nobody cared. That gave me the chance to say, ‘I want to see somebody like me who existed.’

Likewise, at the beginning of The Watermelon Woman, Cheryl says she is unsure what she wants her first film to be about, except that: “I know it has to be about Black women, cause our stories have never been told.”

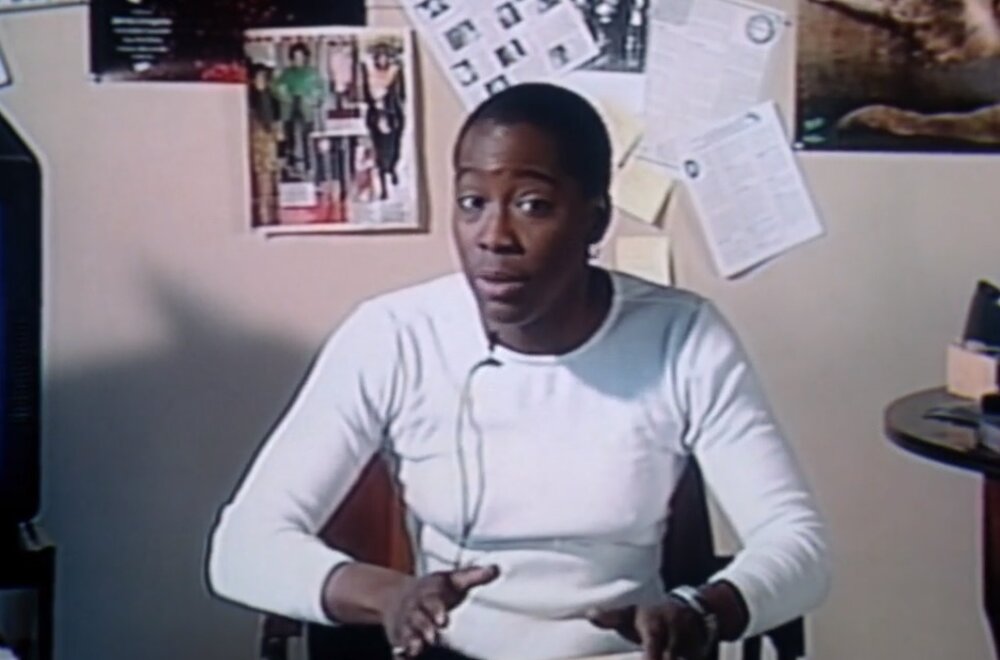

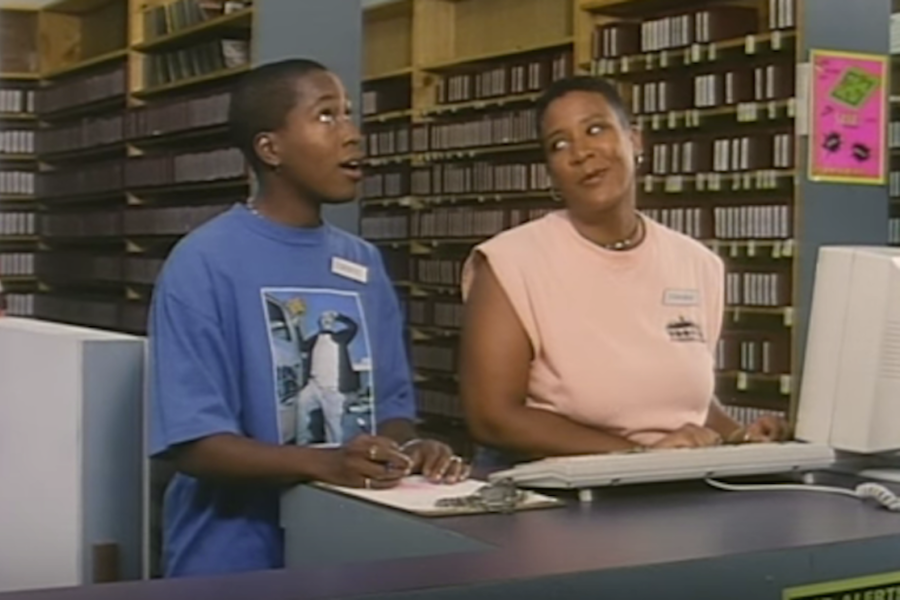

Dunye uses fiction to tell us about a history that is hard to find. Or in her words: “Since it wasn’t happening, I invented it.” She plays a gay video-store employee called Cheryl who is researching a documentary about a Black actress she has glimpsed in a 1930s movie: Fae Richards, known to her audience as the Watermelon Woman. First, Cheryl must take on the gatekeepers. In the library she has to hold her nerve against a sniffy clerk who patronises her research to cover the fact that his classification system doesn’t allow for stories such as Fae’s. There’s no place for her to inhabit in history. In the CLIT (Center for Lesbian Information and Technology – it’s a comedy, after all!) archive, Cheryl has to covertly film photographs that the curators are unwilling to share. Anyone who has tried to research the women in silent film whose credits were stolen, whose contributions dismissed by the first historians, will recognise the thud of a forehead against a blank, brick wall.

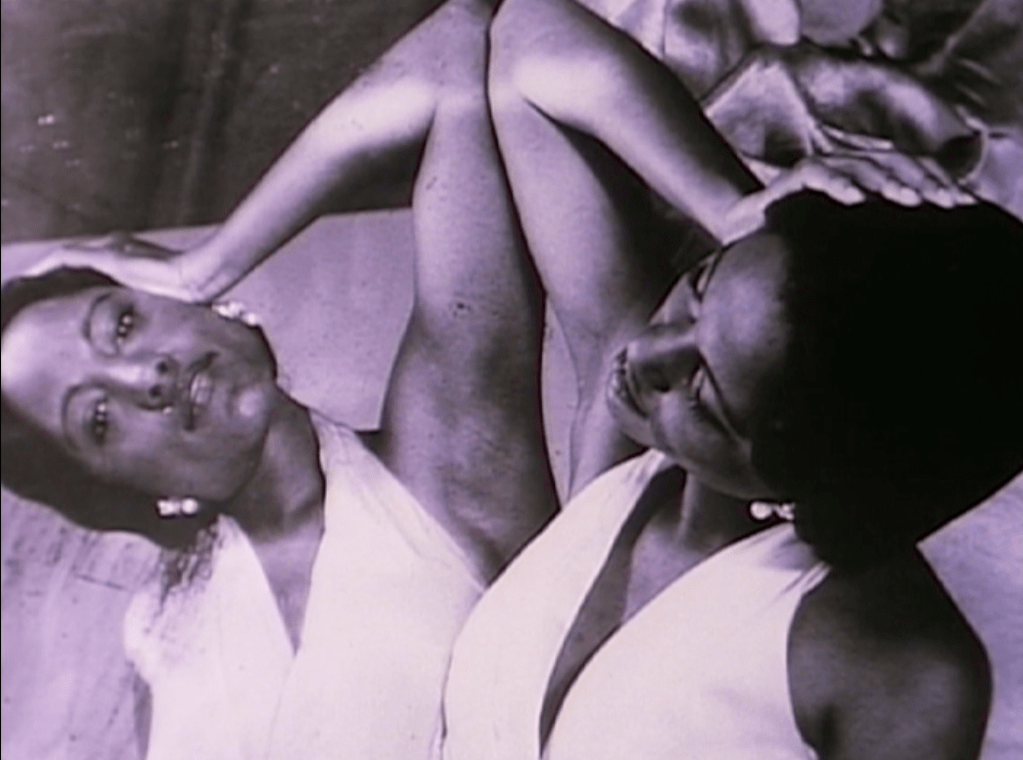

Despite her setbacks, Cheryl finds out Fae’s story, not through the official routes, but by word of mouth, by chance. Fae was a lesbian, which thrills Cheryl, and she also sang in Black-owned nightclubs to a mixed crowd, including infatuated queer girls jostling for a better position. Fae’s story is not told in box-office figures, magazine stories or club receipts, but by memories of sweaty face-offs in the front row. If her story isn’t set down on film or on paper, it will disappear as those besotted girls grow old and die. It’s a problem we all encounter when trying to research Black film performers: mainstream cinema offered them so few parts of substance that the bulk of their careers were spent in revues or in clubs, where the trail can easily disappear.

And the films don’t exist any more: burned, erased, decomposed or simply lost. Silent film historians regularly quote the fact that that 70% or so of pre-sound cinema is missing. The Watermelon Woman reminds us that that isn’t a blanket problem. Some films disappear more than others – especially independent films. Of the around 500 independent “race films” made between 1915 and the early 1950s, less than 100 are extant. Even fewer are available to watch. Certainly not in the model of exhibition Dunye features in her film: an inner-city video store in the 1990s. Of the 22 silent features made by Oscar Micheaux, the most successful Black American film director of the early 20thcentury, only three survive. Kino Lorber’s recent Pioneers of African-American Cinema box set contains treasures and represents the tenacious work of many film scholars, restorers and historians, but we still have an incomplete picture of Black film history.

After the gatekeepers and the absences, Cheryl faces a severe case of misdirection. Fae was in a relationship with her director, Martha Page – a fictional white woman clearly modelled on Dorothy Arzner. In the present, Cheryl is also falling in love with a white woman called Diana (played by Guinevere Turner), who is keen to help with her film… at first.

Even if Cheryl doesn’t get misdirected by Martha for long, I do. Arzner’s story is one of those stories we repeat to tell us that old Hollywood wasn’t quite as bad as all that: a gay woman who directed star-led and yes, subversive, movies in the Golden Age. But having said that, her name is not well enough known, and her films are only very slowly becoming available. When male cinema historians tracked her down for interviews in the 1970s, many of their questions were about the men that she worked with, not her own artistic choices.

Arzner’s relative prominence is a problem too. As with Micheaux in the history of race cinema, her name is invoked as the exception that proves the rule. By pushing the story of their exceptionalism, the work of their peers is sidelined, forgotten – the Faes of this world. The face of cinema history remains monolithically white, straight, male.

And as it turns out, Martha is not the heroine of this story, she is one of its villains. She and Diana let us down together. Cheryl has to find out the truth about Martha from the Fae’s real long-term lover, a Black woman who wasn’t famous, who recalls “unpleasant things from the past”. Having learned the hard truth about Fae’s private life, Cheryl pays tribute to her idol by piecing together a career biography to attach names, dates and facts to the films, stills and glamour portraits she has collected and/or stolen.

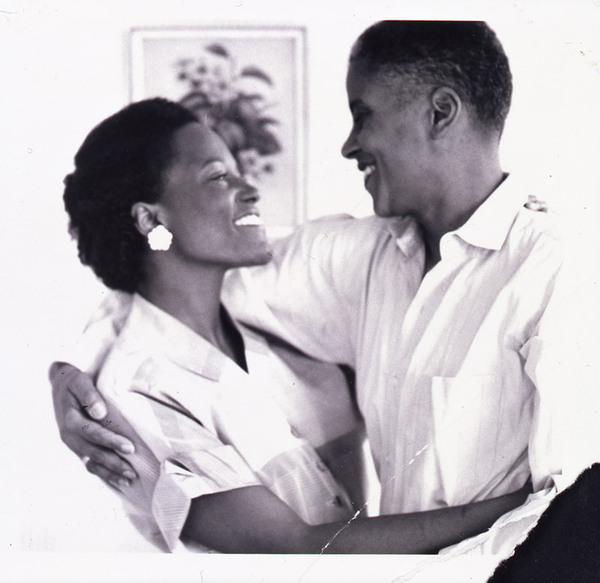

Dunye worked with artist Zoe Leonard to create an impressive portfolio of archive materials for Fae Richards that have the look of the real thing. They used some photos donated by lesbian playwright Ira Jeffries, who appears in the film as Shirley Hamilton. Similar to the setbacks Cheryl encounters researching Fae, Dunye and Leonard were unable to afford the licensing and research fees set by the Library of Congress. For many of us who love, or study, early cinema, collections of ephemera such as this, whether encountered in person, or through digitised archives, are our most tangible contact with lost films, and rarely glimpsed performers. Cigarette cards, trade ads and reproduced images in film textbooks stand in for our experience of watching films we can never hope to see. A small triumph then, that this fictional archive of a queer Black actress was included in Leonard’s 2018 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

I rewatch The Watermelon Woman because it’s funny, romantic and clever, but I take more comfort in its discomforts. I celebrate it for resisting the whitewash we smear over the lonely trailblazers of the past. It reminds me not to fall into the traps I keep setting for myself. The film is a provocation. As Dunye said in that LA Times interview, “There are a lot of stories to tell. I think The Watermelon Woman is there for someone to say ‘I can do better than that.’” Dunye’s film shows me a model of someone who hunts down the truth however hard to find or unromantic it is, and still finds something thrilling there – the spark of connection between Cheryl and Fae as queer Black women, misdirected in a love affair, but united in desire. There’s joy too, in Dunye’s artistry, the act of making a multimedia tribute to character who could otherwise have fallen through the cracks of history, uncredited, mis-identified or just slotted into a narrative structured around anomalies and absences, which excludes the most interesting characters by default.