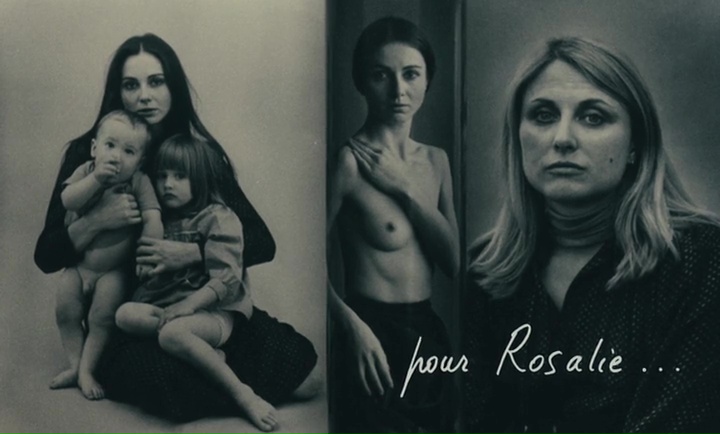

One Sings, The Other Doesn’t. Directed by Agnès Varda, France, 1977

Jemma Desai is a programmer for the British Council and BFI London Film Festival, and curator/writer of I am Dora. Find Jemma on Twitter @dorabyjemma.

One Sings and the Other Doesn’t opens with an inscription. Rosalie is Rosalie Demy: Agnès Varda’s daughter.

The film ends with a lingering close up on Rosalie’s (who plays Suzanne’s grown up daughter Marie, in the film) face. When Varda’s film was restored and played at Cinema le Plage this year in Cannes, Varda’s introductory text to the screening reminded us of her children’s presence in the film.

She reminds us that her camera lingers in the last shot of the film on “18-year old Rosalie Varda Demy” because she “represents the future for women”.

When I first watched the film eight years ago, this detail seemed sentimental, romantic. The film’s politics, its romanticism of female friendship appealed to me, but seemed quite flatly utopian. This time other details, richness, correspondences have emerged.

****

I have been writing letters to my daughter for the past six months.

It’s hard to articulate why I wrote them, and whether she’ll ever read them. It doesn’t matter because in this moment the act of writing is constructive.

The idea of her response feels remote. The letters have served as a thread between my daughter and I as we have steadily separated physically during her first year. They might connect us once again when she moves away once again, through her own autonomous choices later.

Like Suzanne and Pomme, we are two women corresponding, Finding correspondences.

The letters show her we are different. They show her we are the same.

They show her where I have come from, where she has come from.

They might show her how she has become the person she is still to be.

How do women correspond? What is the function of female correspondence (sameness) and correspondence (written and intimate communication)?

In One Sings and the Other Doesn’t correspondences serve as journeys towards and away from each other. They are journeys toward sameness and towards difference. The correspondence between women in the film is startling in its directness and bright in its beauty.

Varda’s film, made from the correspondences of women, is lyrical, it is poetic and at times tragic. The women are unique but at the heart of the film is something perhaps (un)remarkable that has lasting impacts. At its heart are the banal facts of biology that most women living as we do, in a largely heteronormative world, must consider in some form. Varda’s exploration of the choices we women make and why we make them – for lust and romantic love, loneliness, necessity, pressure to conform, youthful vigour – these are choices (and sometimes consequences) facing all women whether we bear children or not.

****

The act of watching is a form of correspondence.

This time I watch One Sings and the Other Doesn’t as a form of correspondence with my daughter.

The film opens with a winter. In the homes of Pomme and Suzanne, every door seems shut. Futures seem remote, even impossible.

As the camera roves between the homes of Pomme and Suzanne, we see an everyday Paris, devoid of glamour. Functional. Oppresive.

This time in this opening I see other films that I will show my daughter. These films have mothers in them, but they are not about motherhood. I will show her the pre gentrification New York of Claudia Weill’s Girlfriends, the perfunctory roaming in a cultureless Brussels in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles and the urgent activism in 90s Paris in 120 BPM.

These are films I will show her when I am afraid that she is so privileged and does not understand who she is, who I am, what others different from her, less lucky than her, face every day.

This time I watch the film for my daughter, worried that she will not see the world as I do.

The film ends in Summer, with the promise of the future.

But it may not be as we imagined.

Through Suzanne’s daughter Marie, who becomes Rosalie in the last moments of the film, Varda shows us the flippant judgements the young bestow on the old.

Why did we marry? Why did we have children? How did we become bourgeois when we thought we were so radical?

Varda makes the film for her daughter, worried that she will not see the world as she does.

Pour Rosalie

Je suis femme

Pour Leena

Je suis moi.