By Clara Bradbury-Rance

But I’m a Cheerleader 20th Anniversary Director’s Cut had its UK theatrical premiere at the Rio Cinema as part of Club des Femmes’ Lesbian Camp: Yes It’s F**cking Political weekender, 5-6 June 2021, with an introduction and Q&A with Jamie Babbit hosted by Clara Bradbury-Rance.

You can now watch Clara’s introduction with close captions, Jamie Babbit in conversation with Clara [transcript available here as a PDF] over on our Vimeo.

*

‘They Were Right … I’m a Homo’: Going to Lesbian Camp with But I’m a Cheerleader

From passively tolerating a sloppy kiss in the front seat of her boyfriend’s car to smiling through a family mealtime replete with meat, gravy and grace, Megan (Natasha Lyonne) keeps her secrets just how she likes them, unconscious and undisclosed under a hairnet. But as it turns out, adorning your locker with Baywatch pin-ups, your bedroom wall with Melissa Etheridge posters and sleeping with your head pressed to an O’Keefe va … sorry, flower cushion, isn’t ‘natural’. That Michelle Williams’s character Kimberly finds kissing her boyfriend ’fun’ while Megan doesn’t is of course not proof of anything but the ritual gamification of adolescent hetero aspiration. Nevertheless, vegetarianism, artwork and iconography are the sure signs of something, and will soon enough be delivered as evidence by witnesses for the prosecution: Megan, teen lesbian cheerleader who just doesn’t know it yet, is primed for an intervention.

As Megan’s conservative Christian parents Nancy and Peter, Mink Stole and Bud Cort uncannily master their zealous hetero parental gaze. Trash queen Stole (who gained notoriety in the films of John Waters) and gay icon Cort (whose parodically aspirational bodybuilding cameo in Pumping Iron I was too much of a ‘distraction’ for the final cut) give us a masterclass in over-performing the performativity of heteronormativity. In turn, it is the arrival of an out-of-drag RuPaul, emerging in a baby blue two piece from a hot pink minivan, that delivers the sucker punch of queer irony.

The whispered accusation – ‘you’re a lesbian!’ – is a moment of reckoning for the film’s queer viewers. Of course she’s a lesbian! What follows is a paradoxical lesson in wrestling with the double edges of queer recognition. The 12-step demands of the minivan’s destination – the ‘True Directions’ conversion camp – leave the ambiguity at the door (or do they?). Love interest Graham (Clea DuVall, translating her invisible girl Buffy vibe for soft butch vulnerability) ’like[s] girls … a lot’ and, make no mistake about it, is also ‘…a lesbian’. But what about Jan, the butch who gradually realises she’s straight? Camp life brings revelations for us all.

In last year’s queer Christmas movie Happiest Season, directed by none other than DuVall, a comedy of errors is initiated precisely by the knowability (or not) of lesbianism. As GBF John, Dan Levy reads our minds with a sarcastically knowing quip: ‘has she ever met a lesbian?’ Style routinely circulates as rumour of queer inevitability. Knowing that a lesbian is a lesbian is presented here as an at-first-sight affair. But gaydar, as one of many ‘procedures of modern queer life’, nevertheless ‘falters before the demands of visual evidence’.1 We might revel in the pleasure of the in-joke but will this evidence really deliver a verdict? What about the cheerleader who is also a lesbian … or the softball player who isn’t?

After all, just think of the many films we can name whose narratives twist on whether someone or other is or isn’t read as queer right away. Exactly twenty years after Cheerleader’s release, Booksmart’s protagonists bicker over whether wearing ‘a polo shirt to prom’ means you’re ‘into girls’, and stereotypes are rebutted with a quick-fire summary of gender performativity: queer theory taken for granted as woke common sense. In Cheerleader it was parody; in Olivia Wilde’s Booksmart, it reads as precocity (before its time, premature). This might signal the start of a new era for queer rep (representation or reputation), but a few of our most pleasurable codes risk getting lost along the way.

Rewatching Babbit’s film in a contemporary context where the UK government still deems it appropriate to ‘debate’ conversion therapy, of course we’re primed to have our hearts broken by homo/transphobia, familial rupture and rejection. ‘Reorienting exercises’ are simultaneously as absurd and traumatic, as agonising and farcical as they sound. In Megan’s case, physical pain is swapped for psychic shame as she masturbates whilst reciting her prayers. And then there’s the unbearable recognition of betrayal by someone you haven’t even been able to acknowledge yet as a lover – followed by the bittersweet shock of the pleasure you realise you’ve been missing out on.

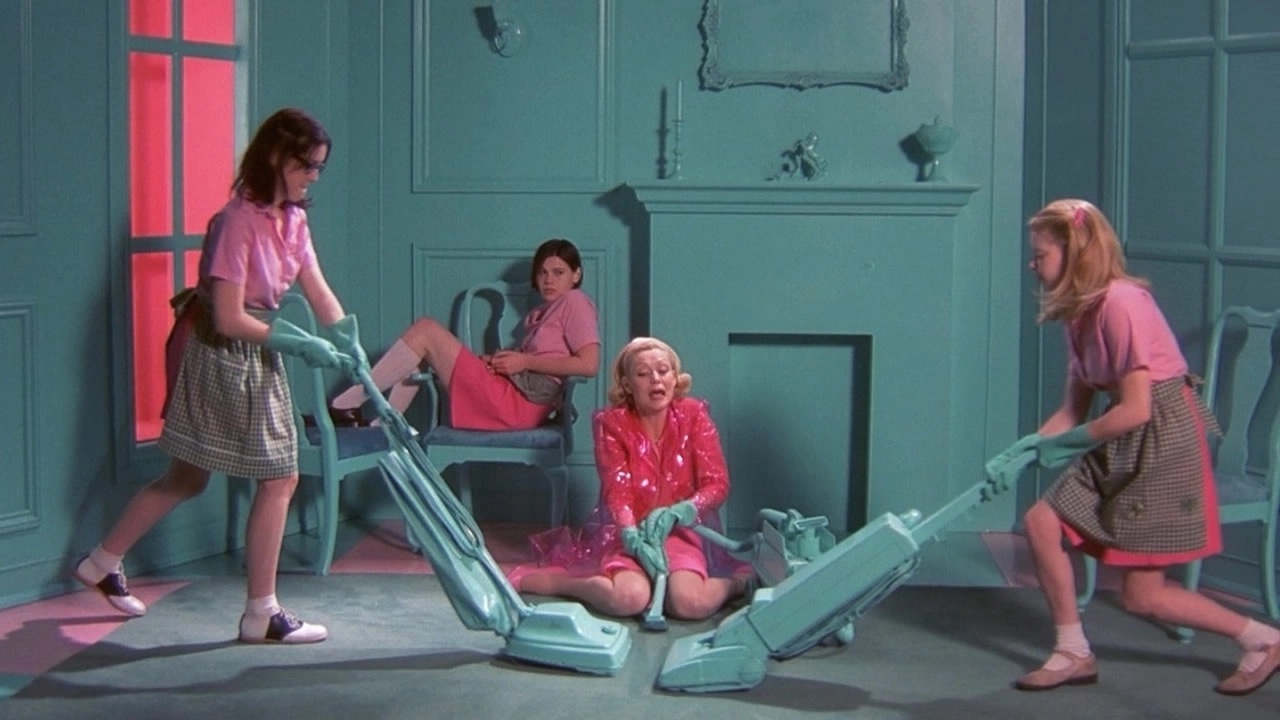

’Rediscovering’ your gender identity with cleaning and hoovering routines that double up as lessons in strap-on technique shows us that every good post-new-queer parody is not just about the queerness of queerness but the queerness of heterosexuality. Being literally taught the motions of heterosexuality – so that you can go through the motions of heterosexuality – surely reveals that ‘all that is natural and healthy’ takes some learning, too.

But Megan already knows these roles off by heart; she just hasn’t incorporated them yet into the perfect queer fantasy. Until now. Surprise, surprise, the therapy doesn’t work, and Megan obediently learns not that straight is great but that gay’s the way (without doing away with the cheers entirely – her ultimate confession is that orgasms compare only, that’s right, to cheerleading).

The film’s charming montages (always accompanied by the chirpiest of 90s indie beats) often show, perhaps controversially, that gendered performances and attachments can alienate one moment and empower the next. Lessons in the norms of feminine friendship only serve to reveal the potential eroticism of, well, ‘friendship’. Shared bathrooms make dressing up in front of the mirror an exercise in yearning observation while the practice of marital tailoring turns role play to foreplay.

Even washing up with a rose-shaped brush (later resurrected, it seems, as a fig leaf in a pre-graduation ‘simulation’ test) is a prelude to flirtation. Housework never looked so good. Graded shades of pink visually bring worlds together: dowdy domesticity, conversion camp, queer collective, gay bar (imagine with me, if you will, a reboot narrated by Janelle Monáe). And then there’s nail painting as queer tenderness (see also Abel Rubinstein’s trans short Dungarees, also showing at Club des Femmes’ camp weekender).

Jamie Babbit’s characters have a habit of wreaking as much havoc as possible, romantically or otherwise, in the cisheteropatriarchy; her next cult hit Itty Bitty Titty Committee was about a group of young activists calling themselves C(I)A – Clits in Action who heckle gay marriage campaigns, quote Audre Lorde and Shulamith Firestone and vandalise municipal buildings by erecting statues of Angela Davis. This politics is profound but it’s also pink, personal, parodic and it pops.

While Cheerleader shares a diegetic decade with Desiree Akhavan’s conversion therapy dramedy The Miseducation of Cameron Post, Babbit’s film combines 60s frills, 70s trash, 80s neon and 90s riot grrrl punk. Take the knowing lesbian citationality of Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman and the affectionate naivety of Maria Maggenti’s The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love and you have But I’m a Cheerleader.

Babbit’s overarching message (delivered by ex-ex-gays Lloyd and Larry Morgan-Gordan, played by Wesley Mann and Richard Moll) is surely that ‘there’s not just one way to be a lesbian’. Lesbianism really can be for everyone! Join the club.