By Annette Kuhn

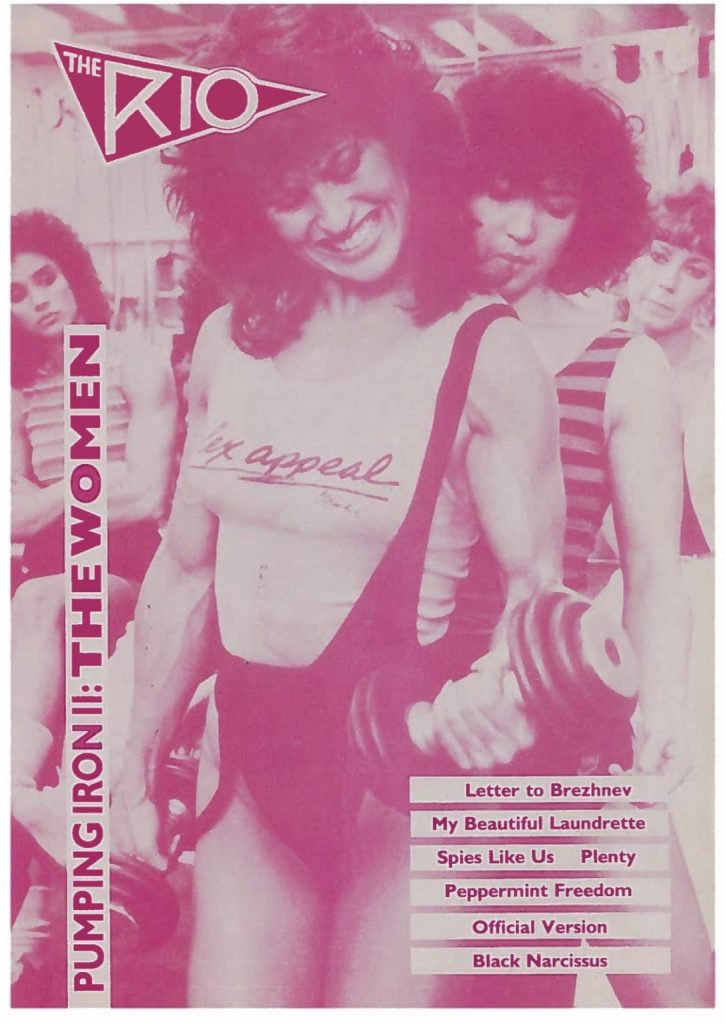

Pumping Iron II: The Women screened at the Rio Cinema as part of Club des Femmes’ Lesbian Camp: Yes It’s F**cking Political weekender, 5-6 June 2021, with an introduction by Sam McBean which you can now watch on Vimeo with close captions. In partnership with Fringe! Queer Film & Arts Fest.

In the mid 1980s, I attended a screening of Pumping Iron II in London. I have no actual memory of the occasion, but it must surely have been the Rio event that’s being celebrated this weekend (puzzlingly, an article I later wrote about the film suggests that the screening took place in 1986, not 1985).1

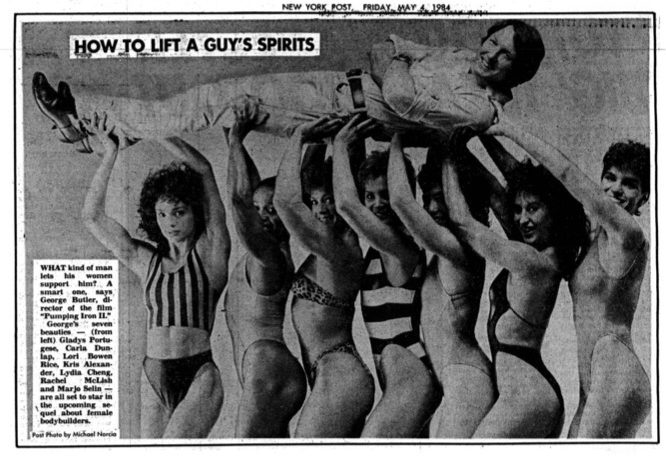

The audience response described in the article doesn’t surprise me at all – it reprises recollections of many a feminist event of the time, when nobody seemed to feel free to enjoy themselves, or to admit to doing so. I observed that the all-female audience in the packed auditorium responded gleefully as one, talking back to the characters, cheering on the “goodies”, booing the “baddies”. Everyone seemed to be having a wonderful time. And yet, perhaps indicating some uneasiness with the pleasures it evoked, the discussion of the film that followed was more-or-less unanimously negatively critical. How to explain the troubling mix of enjoyment and discomfort?

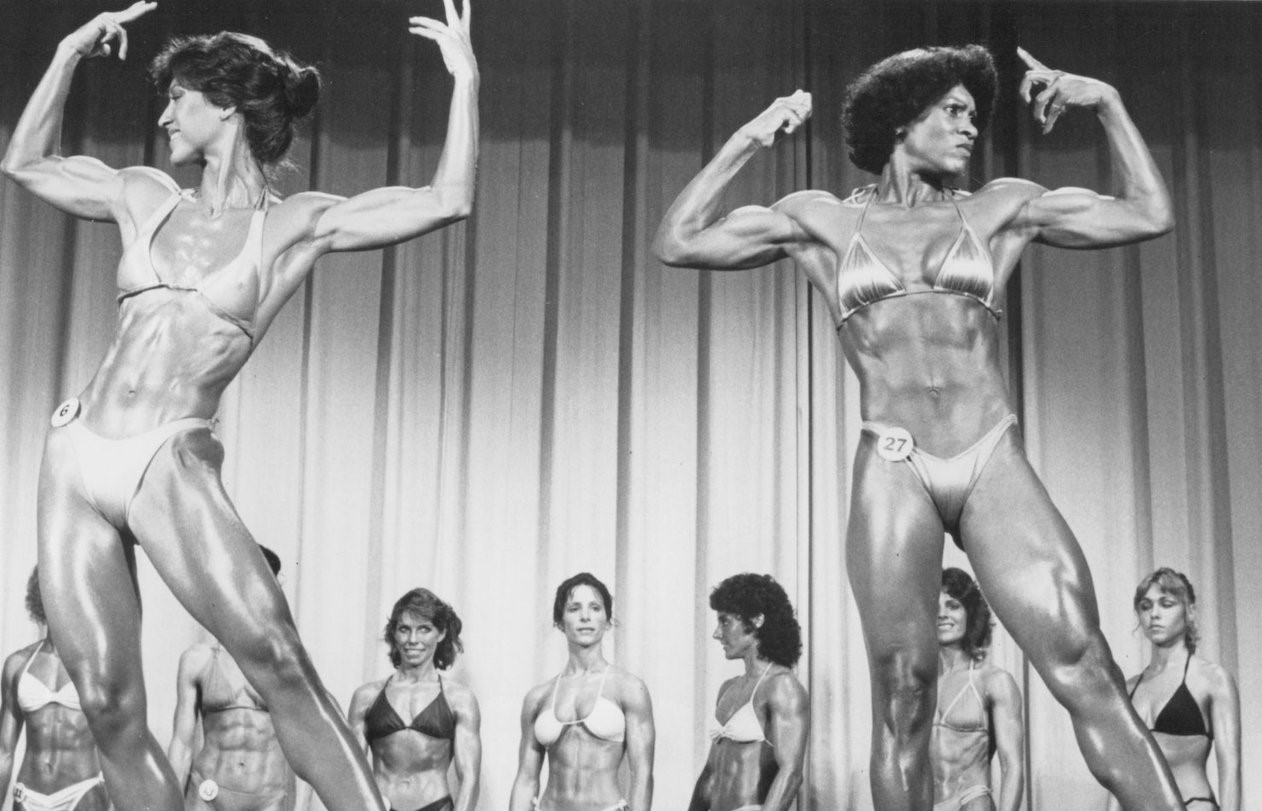

Performance… poses the possibility of a mutable self, of a fluidity of subjectivity. If performance proposes fluidity and the body connotes fixity, the combination of the two in the instance of bodybuilding confers a somewhat contradictory quality on the activity. For bodybuilding is more than placing the body on display, more than just passive exhibition. The fact that bodybuilding is an active production of the body… is impossible to ignore. In Pumping Iron II… there are innumerable scenes emphasizing the sheer hard work involved in the production of [these] women’s bodies.2

The difficulties of such a [narcissistic] mode of identification effectively become a topic of Pumping Iron II, so that the instability of femininity as a subject position, and the discomfort involved in identification with it, are liable to become evident in looking at this film in ways they are not when such relations are more embedded, more submerged in the text.3

In suggesting that the concept of sexual difference was an ideological battleground at the time, my article is very much of its era. Nevertheless, it perhaps has some resonance with today’s identity politics. Is this, as against feminist politics, the context for the film’s reception in 2021? In terms of sexual difference, the article handily distinguishes between biological sex, social gender, gender identity, and sexual object choice. Perhaps it can be said that sexual difference as a thing as well as a concept is now more of a political than an ideological battleground, if you want to make a distinction between ideology and politics.

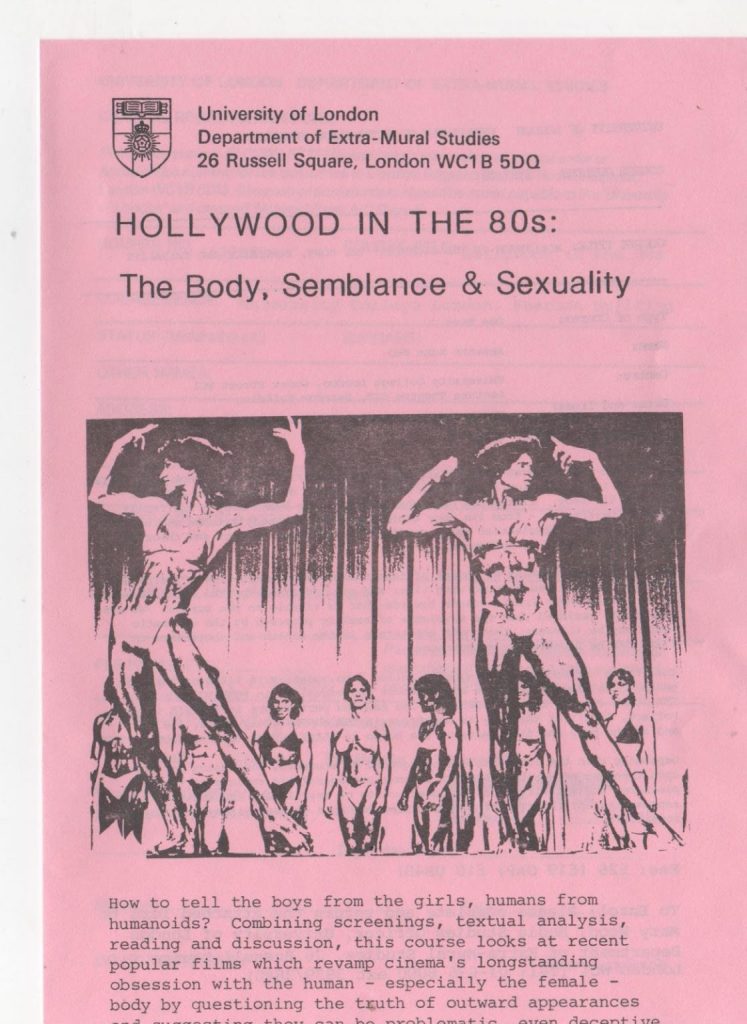

Another, and far more vivid, memory associated with Pumping Iron II has to do with an extramural evening course that I taught in the Autumn of 1987 called ‘Hollywood in the 80s: the body, semblance and sexuality’. It focussed on some more-or-less mainstream films of the time that shared ‘a certain deconstructive attitude towards the body’. Pumping Iron II was among the films screened on that course, which I recall greatly enjoying in the company of a lively group of cinephile feminists. (Other films we looked at included Tootsie, The Hunger and Blade Runner.) I screened two extracts from Pumping Iron II, the credit sequence and the competition first round, and the class discussed these in response to film studies-type questions about image, narrative and spectacle. For example: ‘How does Bev’s body figure in the film in terms of (a) narrative and (b) spectacle. How do these relate? Discuss also in relation to other characters, especially Rachel, Lori and Carla.’

My main memory of that course, however, is of my walk home from the venue at UCL in Gower Street on 18 November, of what that felt like. There seemed to be a lot of to-ing and fro-ing and traffic and sirens, unsettling and very different from the usual evening calm of my neighbourhood. It turned out that the tragedy of the King’s Cross Fire had been unfolding nearby that evening while the class had been absorbed in discussing perversity and the monstrous in cinema. This undoubtedly says something about the nature of cinema memory, an issue – several decades on from my first encounter with Pumping Iron II – that is nowadays more of a preoccupation than the body and its semblances.

*

Annette Kuhn is currently working on ‘Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive’: Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive – 1930s Britain & Beyond, with the University of Lancaster.

- The article in question, ‘The Body and Cinema: Some Problems for Feminism’, was published in Wide Angle, vol.11, no.4 (1989) and is also included in an anthology edited by Susan Sheridan called Grafts: Feminist Cultural Criticism, published by Verso in 1988. A month or two ago I could probably have checked the screening date. In a burst of decluttering I recently threw out a pile of diaries and notebooks from the 1980s and 1990s.

- Annette Kuhn, ‘The Body In Cinema’, p.56. Emphasis added.

- Annette Kuhn, ‘The Body In Cinema’, p.58.