Sunday 8 January 2016, 16:00 ICA

Tickets £7 to £11

From the late eighties through to the late nineties, artist-filmmaker Annette Kennerley created a unique and deeply personal body of 16mm films that explored the emotional ebb and flow of lesbian relationships and sexuality.

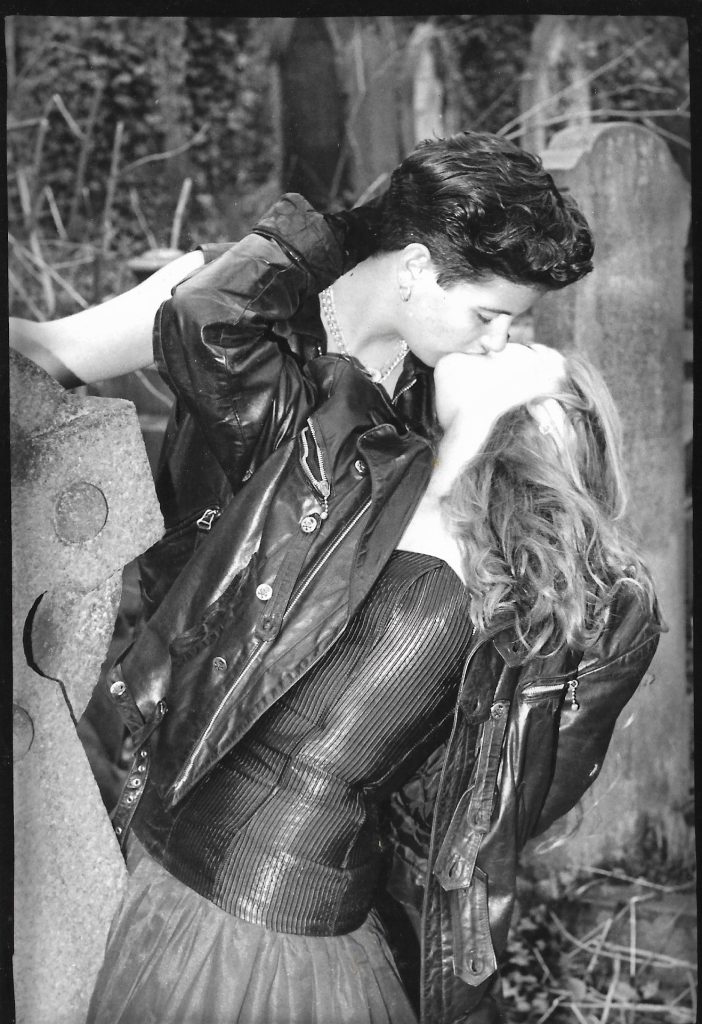

IMAGE COURTESY OF LAURENCE JAUGEY-PAGET

At times joyous, witty and sexy yet tinged with melancholy, these films offer an emotionally frank and at times voyeuristic journey through the memories of contentment, desire and regret, with specific reference to her relationship with her young son Jack. Annette was also an early enquirer into trans relationships and identities, mixing straight to camera interviews with her and Jack’s own playful experiments with gender fluidity.

We are delighted to welcome Annette Kennerley for a post screening Q&A.

LIKE MOTHER LIKE SON Annette Kennerley 5 mins 1994

AFTER THE BREAK Annette Kennerley 14 mins 1998

STRAIGHT ON TIL MORNING Annette Kennerley 22 mins 1991

SEX, LIES, RELIGION Annette Kennerley 7 mins 1994

MATT Annette Kennerley 18 mins 1998

With many thanks to Annette Kennerley and Tom Grimshaw, LSFF

⚡️ ⚡️ ⚡️ ⚡️

“Smoulder and Curl” An Interview with Annette Kennerley – part 2

Part 1 of this interview can be found on the ICA blog

Ahead of our screening on 8th January at the London Short Film Festival, Annette discusses her practice revealing a rich treasure chest of London 80-90s queer film history and cultural memory.

CdF: You began making super 8 and 16mm films in the 1980s in London. What prompted you to use film as a practice and as a lesbian filmmaker where did you find support to realise your aspirations?

AK: I had always expressed myself in writing – diaries and journals since I was a child – and later I became a journalist and worked in the media during my twenties. When I moved to London in 1980 I found a vibrant alternative arts scene and women’s scene. I did an evening class in photography, a six-week 16mm filmmaking course for women at London Film Makers Co-op, a women’s video course at Women in Sync and an evening class making Super 8 films at Kingsway Princeton College. This whet my appetite for filmmaking and amazingly got me into St Martin’s art college which gave me the privilege of access to facilities and student awards and the chance to develop my ideas and skills – days spent in a dark cupboard with the wonderful optical printer became one of my favourite thrills.

There was very little funding around for alternative filmmakers at that time but we had wonderful places like Kingsway College, Women in Sync, London Film Makers Co-op, Cinenova and Four Corners which supported us and enabled us to make our films. Small amounts of funding were dished out by the Arts Council and facilities bursaries by various smaller organisations such as Four Corners and VET. And we all helped each other, too. A group of us started up a queer art group called Visible Images – we met regularly at each other’s houses or studios to share, support and organise several exhibitions of queer work. A few of us clubbed together and bought an old Steenbeck that was being put out to graze (as 16mm became less used as a medium) – it was housed in a friend’s squat and we all used it to edit our films. Everything was done ‘in house’, like a ‘family’ project. This is often how we worked in those days, giving us more control over what we wanted to do, collaborating and helping each other achieve our creative projects in an indie way, with little funding and tight budgets, but without having to conform to the restrictions of major funding bodies or other more corporate organisations. It enabled a greater degree of experiment, spontaneity and creative freedom which was crucial for what we wanted to say without compromise and without having to explain or tone down. In that way, too, it mirrored and reflected our lives at that point in time.

For me 16mm film was very raw, sensuous, hands on, visceral and intimate, a medium I was able to mould, shape and control from loading and shooting on my clockwork Bolex to splicing and editing on a flat bed. It was like creating a painting or sculpture. The aesthetic and the process suited the content which involved emotional and intimate personal exposure. And the preciousness of the film medium meant that every second counted or cost you dearly.

CdF: Jack, your son, has been an inspiration and muse in your filmmaking. Like Mother, Like Son was screened internationally and provoked controversy at the time. Do you think the film would be received differently today?

AK: Yes – I hope it would be and that attitudes might have progressed in some ways. People loved the film and many identified with it – and those who knew me and Jack understood where it came from and how much he was part of it. Maybe it was sometimes difficult for people who didn’t know us to feel comfortable with a young child being such a central part of a film that encompassed and questioned ideas about gender. Some viewers questioned whether Jack had been manipulated or directed to behave in a certain way or to say certain things. The film was almost shown on Channel 4 on a late-night queer slot but these issues were raised in a debate at the television conference in 1994 that voiced concern about how it would be received. It didn’t screen.

I would like to think that audiences today might be more knowledgeable or informed about gender issues. I felt I was giving him the space for expression and exploration – the film began as Super 8 home movie footage of a fairly typical day. This went on all the time in our house. It was unscripted and undirected – Jack later added his own words and reflections to the images. He will be at the screening here on January 8th and he’s very welcome to have a say about what I always see as ‘his’ film.

CdF: You were an early enquirer to document 90s trans identities and relationships in San Francisco and Sydney, we’re particularly thinking about the two films that you made about the emerging FTM community in San Francisco: Boys in the Backyard(1997) and Matt (1998). How did you meet Matt, what was your relationship to him and why did you decide to make those films with him in particular?

AK: I took Sex, Lies, Religion to the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Film Festival in 1993 and stayed there for six weeks. I loved it – it was full of surprises, challenges, revelations and fun. And it was there that I first met the FTM boys through mutual friends. I became close to Matt and Jo in particular and loved hanging out with them, riding around town on their motorbikes, dancing in trash clubs and often just talking in their kitchen or back yard. That’s how the first documentary came about – it was really an ordinary conversation in their yard. I didn’t want to make a conventional documentary or manipulate the footage so I just picked up a camera and we talked. Very little was edited. I found their stories and views fascinating – it raised my awareness of trans issues and I wanted to share this back in London. There was much and often heated debate in the lesbian community about transgender and these were voices that had to be heard. I had friends who were transitioning and it was after this that I went on to help launch the first transgender festival in London.

I was lucky to be able to revisit San Francisco in 1998 to screen Boys in the Back Yard and to reconnect with Matt to make the follow-up film with him. I was interested to see how he was doing five years on and to give him the film frame within which to express his views in what I called a video portrait. I found him so articulate and powerful, fascinating to listen to and very easy to look at, too. It felt important to snapshot how his ideas and emotions had developed and evolved during this crucial stage of his journey and to gain an insight into his battles and beliefs about the world around him and about himself. In this way I felt that Matt 1998 delved much deeper and proved much more reflective and analytical as a film – as if the boy in the back yard had grown up a lot.